Before we paved the streets of San Francisco, little creeks and wetlands were abundant. Today, as in most cities, these natural water features have been replaced by a sewer network that effectively throws away rainwater instead of finding ways to reuse it. But a new 20-year, $6 billion capital program could be the start of a new approach to stormwater management. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission is launching this effort with a handful of small demonstration projects — and the agency wants input from residents in deciding where they should go and what they should look like.

Urban creeks and wetland systems have largely been destroyed in San Francisco, with just vestiges of the city’s eight watersheds visible or touchable anymore (and even then, a lot of sleuthing is involved to find them). But the seasonal rainwater and everyday groundwater they once conveyed to the sea hasn’t disappeared. The city’s native water now runs off streets, roofs and parking lots — or is pumped from underneath basements and streets — into the tunnels and pipes of our sewer system. From there, it’s conveyed to treatment plants, treated just like all the rest of our sewage, and ultimately discharged to the bay or ocean. San Francisco’s sewer system, like those of many older U.S. cities, is called a combined sewer system because it mixes every kind of “nuisance” water together and treats it the same way. This benefits us in some ways, because our system can contain a lot of stormwater runoff and clean it up before releasing it to the sensitive estuarine ecosystem of the San Francisco Bay or to the Pacific Ocean. But there are drawbacks: We are basically throwing away high-quality water instead of reusing it or recycling it. After contaminating this water by mixing it with sewage, we are then paying a lot to treat it back to its original condition. And, we’ve almost entirely lost the ecosystems and natural habitat our water resources once supported.

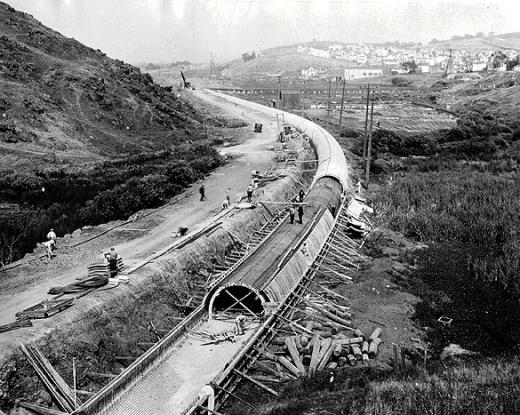

Islais Creek being culverted for burial underneath Alemany Boulevard, late 1920s. Image courtesy the Greg Gaar Collection, via foundsf.com.

For many years, SPUR has advocated for remedying the damages of today’s wastewater system while recognizing the essential economic and public health services it performs. Without wastewater treatment, our city could not exist; if it were to fail for more than a few hours, life would be pretty dismal (and gross). Key retrofits and investments in the system over time have made it much more protective of the marine environment than it was when originally built 80 to 100 years ago. But we could get even more benefits by restoring certain natural functions of our watersheds, and by using nature-based solutions to control stormwater runoff. Referred to as “green infrastructure,” these fully engineered yet nature-based solutions can include bioretention planters, street trees, swales, green roofs, permeable pavement, daylighting creeks and more. Their benefits extend beyond the scope of stormwater treatment and include beautifying streets, creating habitat, sequestering carbon dioxide, improving pedestrian experiences and safety, and enhancing property values.

This retrofitted New Jersey streetscape includes several types of green infrastructure we could use in San Francisco: street trees, vegetated planters and permeable paving. Image courtesy the EPA.

In our 2006 policy report Integrated Water Management, SPUR called on the city to shift its thinking about stormwater problems from remediation to prevention by slowing, percolating, retaining and treating water where it falls — before it enters the piped wastewater system. We recommended a four-part strategy: expanding the urban forest, adopting street and park designs to reduce stormwater runoff, using stormwater for productive uses and promoting green roofs. We also urged a shift in thinking about expenditures — from the up-front bottom line to the long-term return on investment — and recommended that the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC), which has purview over the city’s waters, adopt aseparate rate structure for stormwater to incentivize onsite treatment (a recommendation we advanced again in a recent paper). In 2008, as the SFPUC was on the brink of adopting a long-term sewer system master plan, we suggested that goals for this plan include a green infrastructure approach to managing stormwater and creating environmental benefits. In the last few years, other major U.S. cities such as Philadelphia, Washington, D.C., and Portland, have launched city-wide green infrastructure strategies, in many cases because it was shown to be the most cost-effective, economically beneficial alternative for meeting federal clean water requirements.

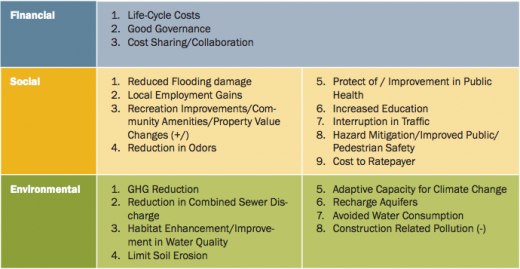

In the seven years since, we’ve continued to advocate for the “big idea” of a multi-billion dollar sewer system capital program, working with other SF groups such as SWAle and aided by great technical work from the SFPUC Urban Watersheds team. Now, the momentum is finally building in San Francisco. The city has adopted goals and is now pursuing the first phase of its sewer system upgrade —called the Sewer System Improvement Program or SSIP — a twenty year, $6 billion capital program to improve seismic reliability and sustainability of the system. A sizeable chunk of that investment, around $400 million, is currently planned for green infrastructure. In 2012, the SFPUC published an Urban Watershed Framework that described how it plans to evaluate and implement green infrastructure projects by watershed, and select alternatives according to a “triple bottom line” evaluation, which assesses a project on financial, social and environmental outcomes.

Urban Watershed Project “Triple Bottom Line” Evaluation Criteria

Source: SFPUC, Urban Watershed Framework, 2012, page 17.

But even with this big financial commitment made and a project selection process identified, there is a lot of work ahead before we can make the big transformative moves. Currently, the SFPUC is undertaking a broad and deep watershed characterization and assessment process for each of the city’s eight watersheds. This will reveal sewer system weaknesses, flooding or groundwater problems, soil types and more. At the same time, the agency is leading an effort to quickly site, design and install eight green infrastructure early implementation projects (EIPs) scattered around San Francisco. These small pilot projects will serve three really important functions. First, they will show people what’s possible with respect to transforming the streetscape — and hopefully convince ratepayers that these retrofits are worth paying for. Second, they will give us some experience with project performance. We don’t really know, other than through computer modeling, how successful the wide variety of green infrastructure types may be in San Francisco’s unique climate and urban environment. Some types of projects may perform better than others, and on-the-ground experience is the best way to get a sense of which types of projects we’d like to deploy more widely, and where. (We don’t have a lot of green infrastructure in the ground to date, so a smattering of diverse pilot projects is a reasonable place to begin.) Finally, the EIPs will teach us best practices in stakeholder engagement, design and maintenance for the various types of green infrastructure we might want to roll out more widely over the next 20 years. They’ll help us learn, so by the time we’re able to make the $400 million commitment through the SSIP, we’ll get the best bang for the buck (considering the triple bottom line, of course).

The SFPUC aims to build all the EIPs in the next three to five years, and here’s where you come in. Right now you can provide input on the first EIP underway, the Mission & Valencia Green Gateway. This project, on Valencia Street between Mission and Cesar Chavez, will build on previous planning efforts by the SF Municipal Transportation Agency and SF Planning Department to improve community spaces and pedestrian safety through traffic calming. Next, you can join a planning charrette on Saturday, June 1, here at SPUR, to identify opportunity sites in the Channel and North Shore Basin watersheds, and help the SFPUC plan stormwater solutions in the most densely urbanized part of our city (RSVP required).

SPUR will be closely tracking the SSIP, as we have for years, to ensure the SFPUC stays committed to green infrastructure, and to the social and environmental outcomes we believe the city can have with a 21st-century-ready wastewater system. We may have once buried the creeks of San Francisco to accommodate the city’s growth, but we now know that a livable city can sustain and benefit from both.