Bus rapid transit (BRT) projects can be transformative, as we have learned from cities like Cleveland in the U.S. and global examples like Mexico City. But making space on streets for travel modes other than the car is a challenge for cities and transit operators around the world. The Bay Area has five BRT projects in development today, and each has met with difficulty and delays.

Last month one of these projects, the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority’s Santa Clara/Alum Rock line, made the move from planning stages to design and construction. This 7.2-mile route through downtown San Jose will provide high-frequency bus service (every 10 minutes) and connect two major transit hubs — Diridon Station and Eastridge Mall. This line will converge with the Stevens Creek and El Camino BRT lines in Downtown San Jose. When these three BRT lines are combined with local service, an estimated 84,000 daily bus riders are expected to travel this corridor in 2030 (compared with 31,000 in 2008).

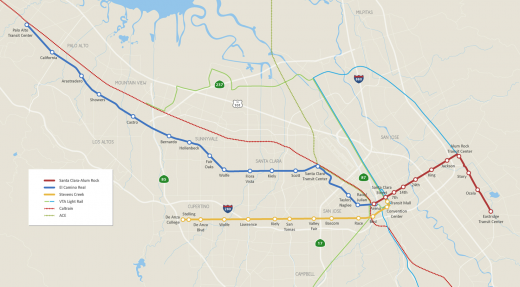

Planned Bus Rapid Transit Projects in the South Bay

Enlarge image >>

VTA’s planned bus rapid transit projects. The Santa Clara/Alum Rock BRT line is shown in red. This corridor currently has some of the highest bus ridership in the region. Image courtesy VTA

BRT expands a transit network in places where there’s a demand for fast and frequent transit service — but where rail might not be justified. It can represent a big enough infrastructure improvement to support new development and more livable communities. In Cleveland, development of the Euclid Avenue Healthline BRT has led to $4.3 billion dollars in spin-off investments and more than 13.5 million square feet of new development.

What makes BRT tricky is in the details of integrating it on existing streets. Where will stations be located? How will giving a lane to BRT impact auto traffic and parking? How will changes to the streetscape affect local businesses? Particularly in commercial districts and downtowns, there can be many stakeholders — and many negotiations about how to allocate streets and sidewalks. For the Santa Clara/Alum Rock project, SPUR worked with all the parties involved to try to maintain BRT best practices while also mitigating community concerns. The issues we grappled with illustrate what makes BRT a challenge to implement:

1. WIN: There will be a BRT station in front of San Jose City Hall — not a block away. SPUR supported locating the City Hall BRT station directly in front of City Hall (between 5th and 6th streets), rather than one block east, as the city initially preferred due to security concerns. We argued that locating in front of City Hall would save a large amount of money (the original location would have required property acquisition costing hundreds of thousands of dollars), activate City Hall’s plaza and better serve major destinations – City Hall and San Jose State University. Additionally, the City Hall station represents an important opportunity for local government to lead by example and embrace BRT at its front door.

2. WIN: The downtown San Jose station has the right design for its location. Initially, the downtown station (on Santa Clara Street, between 1st and 2nd streets) borrowed its design from other BRT stations in suburban locations. A BRT stop on the median of a busy suburban boulevard needs heavy design elements to make patrons feel safe. But a downtown station needs the opposite — light elements that don’t clutter the sidewalk or block pedestrian access. Based on SPUR’s suggested refinements, city and VTA staff and their consultants made considerable modifications, creating a station we believe will integrate much better with the downtown streetscape. Changes such as the size and placement of awnings and benches go a long way toward improving aesthetics, pedestrian flow on the sidewalk and patron comfort while waiting for transit.

The revised downtown San Jose BRT station design changed the size and placement of street furniture to help it integrate with the sidewalk. For example, benches were turned sideways so that transit patrons would not sit with their backs to the sidewalk. Image courtesy VTA.

3. OUTCOME UNCLEAR: The current service design does not prevent BRT buses from getting delayed behind autos. Numerous changes in the design of the downtown BRT service have been considered over the past year. VTA’s original plan would have keep BRT buses in mixed-flow traffic lanes with other vehicles. This design provided sidewalk bulb outs for safe and efficient bus loading and avoided conflicts between autos turning right or left across bus traffic. But it also would have required cars to wait or move around loading buses, so City of San Jose staff and the San Jose Downtown Association asked VTA to modify the design. The revised design attempts to accommodate four lanes of autos and requires buses to move in and out of mixed-flow traffic to load and unload in the curbside lane.

Since this design would delay buses, potentially taking the “rapid” out of bus rapid transit, SPUR advocated for VTA to study dedicated bus-only lanes throughout the downtown. VTA found that dedicated lanes would significantly improve bus travel times, but the city — facing concerns from downtown business interests about slowing travel for cars — opposed the idea. When a coalition of organizations including SPUR, TransForm, Silicon Valley Leadership Group, Greenbelt Alliance and Working Partnerships voiced concern, VTA developed “transition lanes,” which would put a dedicated space before and after each stop to help buses move in and out of mixed-flow traffic faster.

Downtown interests have now advocated against transition lanes in order to retain the 10 spaces of on-street parking that would be lost — a position SPUR firmly disagrees with. The current design does include transition lanes, but because they are simply painted on the ground, they have remained up for debate by the VTA’s board. The timing of transition lane implementation, along with whether to allow left or right turns across bus traffic, has now been left to a VTA advisory board. We have not yet solved the problem of car traffic delaying rapid buses in Downtown San Jose.

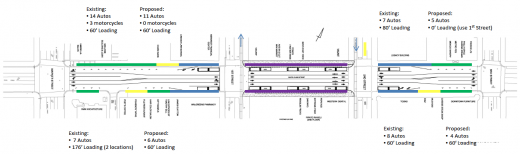

Santa Clara BRT Proposed Station Layout

Enlarge image >>

The most recent service design for the downtown BRT station. The blue areas are “transition lanes,” space reserved for buses to pull in and out of traffic. Green areas are parking and yellow represents loading zones. Local businesses have opposed transition lanes due to the loss of 10 parking spaces downtown. Image courtesy VTA

What Did We Learn?

VTA and the City of San Jose deserve much recognition for moving the Santa Clara/Alum Rock BRT project forward, but their success came at a cost to the BRT service. Just 1.9 of the Santa Clara/Alum Rock project’s 7.2 miles will be separated from autos on dedicated lanes. According to the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy’s BRT Scorecard, the Santa Clara/Alum Rock project would be called “basic” BRT. As we move other Bay Area BRT projects forward, we can aspire to bronze, silver or gold rankings by including dedicated lanes and adding rider amenities rather than removing them.

BRT decisions will continue to be made across the region in the months ahead. VTA is now looking at seven possible alignments for the 17.3-mile El Camino BRT route, which will serve the cities of San Jose, Santa Clara, Sunnyvale, Mountain View, Los Altos and Palo Alto. The alignments being studied include a dedicated lane for BRT throughout, which VTA is studying despite opposition from leaders in many of those cities. In San Francisco, after many years of negotiations with stakeholders, the San Francisco County Transportation Authority is seeking to certify an environmental impact report for BRT on Van Ness Boulevard in July. This project is being proposed as “fully featured BRT,” which includes dedicated lanes for BRT and pedestrian improvements along Van Ness. As they move ahead, these projects will need support from many sources to retain their defining features.

Thanks to special buses and branding, transit signal priority and rapid boarding, the Santa Clara/Alum Rock project will likely provide many of the benefits of BRT. And there will be many opportunities to create higher standard BRT service by adding quality pedestrian and bike facilities, clear wayfinding, real-time travel information and supportive parking policies. But when we choose not to give BRT riders priority on the street, we set BRT up to fail in its potential as “rapid” transit.

BRT has proven to be a test of our best policy intentions. The City of San Jose’s General Plan boldly defined a policy of reducing driving alone from 80 to 40 percent of all commutes by 2040. This is a worthy and ambitious goal, but to get there we must give BRT projects the support they need to succeed.

Learn about Mexico City’s BRT at our June 27 forum in San Jose >>