Over the next 25 years, the Bay Area is projected to add 2.1 million new residents and 1.1 million new jobs. Accommodating this growth in a way that reduces driving is one of the goals of Plan Bay Area, a long-range vision for the region that integrates land use and transportation planning. (For details, see our post What You Need to Know About Plan Bay Area.)

In November, planning officials from San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland met to share their progress in implementing the plan with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission and the Association of Bay Area Governments. This was the first time the region’s three largest cities have presented their plans together since Plan Bay Area was adopted in 2013. SPUR is preparing to open an office in Oakland and expand our focus to the three central cities, so we were eager to understand how each is approaching implementation and how they can coordinate their efforts.

Why focus on these three cities? Plan Bay Area projects that nearly 40 percent of both job and housing growth will locate in San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland. While there are many places throughout the Bay Area that will experience significant growth, the three central cities are home to the bulk of the region’s transit, as well as its highest-priority transit investments: extending BART to San Jose and extending Caltrain to the Transbay Transit Center. The success of these transit systems and the development that takes place around them will do the most to determine the region’s ability to grow in a way that reduces dependence on cars.

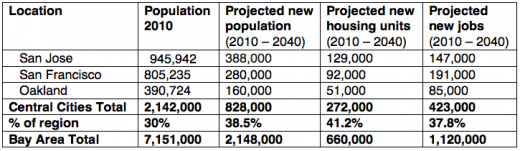

Plan Bay Area Growth Projections 2010–2040

In 2010, San Jose, San Francisco and Oakland had just under 30 percent of the region’s employment and population. According to Plan Bay Area, they will take on nearly 40 percent of all regional growth. That amounts to more than 9,000 housing units, 27,000 people and 14,000 jobs per year for 30 years. Among the three, San Jose is projected to gain the most in population while San Francisco is projected to gain the greatest number of jobs.

Source: Plan Bay Area

What was clear across all three presentations to MTC and ABAG is that each city is confronting a similar set of challenges, though in slightly different ways:

- How to balance the current strong demand for residential development in the urban core with the need to add jobs in transit-oriented locations, particularly downtown.

- How to manage the growing housing affordability crisis in an era with limited funding for affordable housing and uneven market dynamics.

- How to ensure that new transit investments result in growing transit ridership through both well-planned transit and responsive land use.

The following are a few highlights from each city:

San Jose: Lots of growth allowed by the city’s general plan, but detailed urban village planning will be necessary

San Jose’s implementation of Plan Bay Area follows the urban growth strategy set forth in its 2040 General Plan, which shares the same timeframe as Plan Bay Area. San Jose’s general plan directs development into 70 or so urban villages — centers that have the potential to be the anchors of future walkable neighborhoods. The city is currently planning a number of these villages, including South Bascom, the Alameda and West San Carlos. This is a very ambitious planning agenda for a small planning staff. San Jose will be challenged to achieve a better balance between housing and jobs, to attract employers to transit-oriented locations and to substantially reduce its residents’ and workers’ reliance on cars.

Review San Jose’s slides here.

Watch a video of the presentation by Michael Brilliot of San Jose’s Planning Department here.

San Francisco: Current zoning allows for the housing projections, but not for the job projections

In San Francisco, the recent completion of a series of neighborhood plans has laid the planning groundwork for allocating new jobs and housing. San Francisco has identified capacity for 97,000 new units of housing by 2040 (5,000 more than the 92,000 Plan Bay Area calls for). The city is also in the enviable position of being 40 percent of the way toward achieving its total job projection, having added more than 70,000 jobs since 2010. Yet the city has only zoned capacity for 143,000 additional jobs — 50,000 short of Plan Bay Area’s full projection. This is in part because only 10.5 percent of land in San Francisco is zoned to allow offices, a key building type for the many of the future jobs.

San Francisco has four specific challenges that come up in its implementation of Plan Bay Area: addressing resilience (considering that most of the areas where it plans to add jobs and housing are especially vulnerable to sea level rise), preserving employment diversity, investing in transit and other transportation needs of the growing population, and making sure new growth strengthens the quality of existing neighborhoods and places.

Review San Francisco’s slides here.

Watch a video of the presentation by Gil Kelley of the San Francisco Planning Department here.

Oakland: Recent specific plans lay the groundwork for growth, but more will be needed

Oakland’s planning process has centered on a series of specific plans for areas near transit, including Broadway Valdez, West Oakland and Lake Merritt/Chinatown. The plans create a framework for growth and provide greater certainty about what kind of development is desired in different locations. A downtown specific plan is next. Projects like Brooklyn Basin are expected to add more than 3,000 units (likely over a decade). Oakland’s challenges include: managing rapid price increases in a period that has had virtually no development (something that will likely change in 2015), attracting new employers and significant job growth throughout the city, and increasing local revenues to pay for investments in infrastructure.

Review Oakland’s presentation here.

Watch a video of the presentation by Oakland Planning Director Rachel Flynn here.

What’s Next

How these cities resolve their challenges and manage future growth will have ramifications for the entire region. For example, BART is nearing its capacity to carry East Bay workers to San Francisco (particularly at the Montgomery and Embarcadero stations). If Oakland adds a significant number of jobs around its BART stations, it would balance out demand on the system and ease additional pressure on the transit commute to downtown San Francisco. But if an Oakland boom brings significantly more housing than jobs (especially in downtown), the increased number of commuters to San Francisco will make BART crowding worse.

Understanding the regional impacts of where jobs and housing locate is core to the success of Plan Bay Area — and central to a common challenge facing all three cities. Quite simply, the demand for residential development is stronger than the demand for commercial office development. To achieve the reductions in driving that Plan Bay Area calls for, the three central cities will need to see a significant increase in employment in their transit-accessible cores. These are great places for housing, but they are critical places to add jobs given the billions the region is investing in transit to these centers (and the fact that job locations are a bigger driver of transit ridership than housing).

The success of Plan Bay Area depends on San Francisco, San Jose and Oakland acting as leaders for communities throughout the region. Yet last month was the first time in recent memory that the three central cities came together to share their planning work with key leaders and each other. Better communication on the plan’s implementation is crucial to its success and to laying the groundwork for a stronger regional plan when it is updated in 2017.

SPUR’s central city strategy sees the growth choices made by San Francisco, San Jose and Oakland as key to the future shape of the region. Plan Bay Area offers the greatest opportunity in a generation to coordinate around a common vision. But land use decisions are ultimately local. We are building an organization capable of helping the three cities do great local planning. But we are also committed to the shared goals of the region: to concentrate growth in places that are walkable; to increase access to high-quality transit and economic opportunity; and to preserve open space and improve public health. In addition to working within each city, we will also help San Francisco, San Jose and Oakland work with each other to share lessons and support our common regional goals.