Both Caltrain and highways on the Bay Area Peninsula are more crowded than ever. Will we solve the area’s transportation challenges in the future — or will things only get worse? Will it be easy to grab a train up or down the Peninsula? Or will it require hours on Highway 101 to get anywhere? Can we find a way to fund the transit we want?

SPUR is working with a group of partners to shape a vision for the Peninsula travel corridor. We think the future is promising, and one of our major projects for 2016 is to make recommendations for how passenger rail and other transit can be the backbone of the solution.

Part 1 of this blog post took a look at how Peninsula transportation came to be what it is today. In Part 2, below, we explore what’s next. First we’ll look at the many great projects slated for the coming years. Then we’ll outline the work SPUR and its partners are doing now: the big issues left to solve and the questions we’re seeking answers to.

Peninsula rail will be faster, more frequent and more pleasant.

Caltrain’s evolution from a small private railroad to all-day public transit continues. The agency has embarked on a two-part, $1.7-billion modernization program, which will provide cleaner, quieter, faster and more-frequent service. The first part of modernization is electrifying the 51.4 miles of track between San Francisco and San Jose and replacing 75 percent of Caltrain’s diesel fleet with electric trains. The new trains will be quieter and less polluting, and they’ll be able to operate more efficiently, running six trains per peak hour instead of the current five. The second piece of Caltrain modernization is a new train control system, which will allow trains to run closer together, making increased frequency possible.

Caltrain has begun to discuss the investments that will be needed following electrification. These projects, known as Caltrain Modernization (CalMod) 2.0, will be essential to keeping up with demand and include more electric train cars and station improvements so that Caltrain can run longer trains.

Traffic backups caused by rail crossings can be addressed with grade separation projects, such as this one recently completed in San Bruno. (Source: HNTB)

Grade separations are making rail more compatible with surrounding cities, which want to eliminate local traffic delays when trains go by. Train tracks are already separated from roads at 78 out of Caltrain’s 120 crossings, and at least five more projects are planned (Palo Alto, Burlingame, Menlo Park, San Mateo, and the border of San Bruno and South San Francisco). Traffic backups caused by “gate down time” are a consistent and significant source of public concern regarding the growth of rail service, which means projects to separate tracks from roads will make it easier to expand rail service.

High-speed rail service will serve the Peninsula corridor.

Thanks to an agreement forged in 2012, California High-Speed Rail plans to use the Caltrain rail corridor to connect to San Francisco via San Jose, with a stop in Millbrae and perhaps one other city. In order to support up to four high-speed rail trains on the corridor, there will need to be new passing tracks, curve straightening, and maintenance-yard and station modifications. Some people might use high-speed rail trains instead of Caltrain for local trips on the Peninsula.

Caltrain and high-speed rail will have a downtown San Francisco station.

Caltrain electrification lays the groundwork for bringing Caltrain and high-speed rail to downtown San Francisco at the new Transbay Transit Center at First and Mission streets. Thanks in part to the Transbay Center District Plan, this neighborhood will be the densest cluster of employment in the Bay Area, with 176,000 jobs within a half-mile walking radius of the transit center. (That’s as many jobs within walking distance as the rest of the Caltrain stations combined.) The $2.2 billion transit center will include a bus terminal that can accommodate 300 buses per hour.

The planned extension of Caltrain to downtown San Francisco will bring it to the Transbay Transit Center, which is currently under construction. Courtesy the Transbay Transit Center.

Getting Caltrain and high-speed rail to downtown San Francisco also requires a 1.3-mile tunnel (known as the Downtown Extension) from the current 4th and King station to the new Transbay Transit Center. This $2.5 billion (or more) project has received environmental clearance but is not yet fully funded. SPUR helped develop a concept for changing the tunnel path for Caltrain and high-speed rail, enabling the boulevarding of I-280 and possible development at the railyards at 4th and King. The feasibility of these big moves is now being evaluated by San Francisco’s Railyards Alternatives and I‐280 Boulevard Feasibility Study.

Cities are growing around rail.

Many of the Peninsula cities that grew up around rail decades ago are planning to add new jobs and housing around Caltrain stations. Cities with plans in the works include San Jose (Diridon and Tamien station areas), Santa Clara, Sunnyvale, Mountain View, Palo Alto (California Avenue), San Mateo (Hillsdale and Bay Meadows), Millbrae, South San Francisco and San Francisco (Transbay Center District Plan). Jobs farther away from Caltrain stations, at places such as Stanford Research Park or North Bayshore, are also increasing their rail usage, facilitated by last-mile services such as shuttle buses, light rail and bicycles. Furthermore, the Grand Boulevard Initiative — a re-imagining of El Camino Real — is centered on transit.

Caltrain will be better connected to the rest of the Bay Area rail network.

A downtown San Francisco station will connect Caltrain with BART. In the future, you will be able to transfer from Caltrain to the BART Silicon Valley Extension at Diridon and Santa Clara stations and to Muni’s Central Subway at 4th and King. There will also be more Altamont Commuter Express and Capitol Corridor trains meeting Caltrain at Santa Clara and Diridon. Diridon Station in San Jose may soon be the busiest train station in the Western United States, with more than 200 trains per day. A second transbay rail tunnel, now under discussion, could create an entirely new link between Caltrain and the East Bay. (The new tunnel could carry standard rail instead of, or in addition to, BART.)

A Cohesive Vision for the 21st Century

The transportation projects and plans described above are essential. But they are not a complete package to keep up with our 21st-century transportation needs. The demand for rail might exceed the supply; delays on 101 will likely continue to get worse; and bus alternatives to get up and down the Peninsula might not become available, or be attractive.

Innovations such as better real-time information, carpooling, and eventually autonomous cars or buses will inevitably emerge and improve mobility. However, there are big policy innovations (such as highway tolling) and strategic investments (such as grade separations, passing tracks and station upgrades) that we need to start planning and funding today. And we have to do this in a fragmented environment: Transportation in this corridor is planned and operated by three counties, 20 diverse cities and at least 16 other local, regional and state transportation agencies.

Through the Peninsula/Caltrain Corridor Vision Plan, SPUR and its partners — the Silicon Valley Leadership Group, Stanford University and the San Mateo County Economic Development Association — aim to develop a vision for how passenger rail and other transit can move far more people in this corridor. Together we are focusing on the following questions:

Can rail be the main backbone for moving people along the Peninsula?

Can Peninsula rail feel like Swiss Railways or the Berlin S-Bahn, with seamless connections to local transit and longer-distance rail services? What are the best operating scenarios possible for an electrified Caltrain: Could you one day expect a train to arrive every ten minutes and never need to consult a schedule? How many more people could rail serve? What trains cars, grade separations, tracks and station improvements will be needed? And are there some brand new rail lines we need to consider?

What will it take to make Caltrain a high-frequency and connected system like the Berlin S-Bahn? Photo courtesy flickr user Phillip Bouchard

How do we make highways and rail work together?

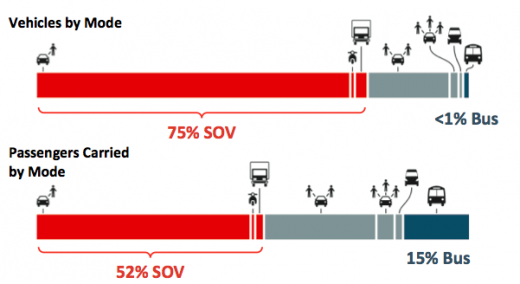

Buses on highways could be a fast and flexible transit option — but only if we manage highways the right way. Today, the average occupancy of vehicles on Highway 101 on the Peninsula is about 1.5 people per vehicle. While less than 1 percent of the vehicles on 101 are buses, they carry 15 percent of the people. It makes sense to encourage more full cars and more buses. We can accomplish this with high-occupancy vehicle and/or high-occupancy toll lanes, which allow non-carpool vehicles to pay to use high-occupancy lanes. Changing a fee gives us a tool to control how crowded the road gets. San Francisco and San Mateo counties are currently studying how to better manage their freeway segments, and Santa Clara County is creating two high-occupancy toll lanes. How should 101 work across these three counties?

Moving More People on Highway 101

Buses take up less than 1 percent of space on 101 today but move about 15 percent of the people during the peak hours. This shows that adding more buses can help us move far more people on 101 — without adding more cars. Source: SPUR analysis, based on Metropolitan Transportation Commission data.

How do we make it seamless and intuitive to get to and from rail stations?

A majority of Caltrain riders today get to and from stations without a car — 67 percent bike, walk or use transit. As we double or triple the amount of train service, how can we continue to get most riders to and from stations using these sustainable travel modes? What will it take to create certainty that when you arrive at a rail station, you won’t be stranded and will instead be able to travel that last mile or two to your final destination?

How do we fund the big moves?

We have almost funded the electrification of Caltrain, but we still need to fund the other projects in the pipeline — and any new projects we identify to upgrade rail service or stations. How much money do we need to achieve our vision? What are the best sources? What is a stable funding stream for Caltrain (which has no significant dedicated funding today)?

The Bay Area Peninsula is known as the heart of the world’s innovation economy. Keeping up with growth requires us to step up our game: a bigger vision, spending money more strategically, and building more consensus on what the solutions are.

Tell us your vision for the future of transportation on the Peninsula corridor.

Take our survey >>