Sometimes, all it takes for an innovative policy to spread is for local leaders in one region to make the leap and prove a better future is possible.

That happened when Bay Area regulators passed a first-in-the-nation air quality standard for heating equipment. Starting in 2027, when a polluting water heater burns out, it must be replaced with a clean electric alternative. The same applies to residential heating, ventilation, and cooling (HVAC) systems starting in 2029 and commercial water heaters in 2031.

The Bay Area’s leadership has already sparked a movement. Since the rules were passed, the California Air Resources Board has set goals to phase out the sale of residential gas heating equipment by 2030, and nine states have pledged that heat pumps will be 65% of residential HVAC and hot water equipment sales by 2030. Global heat pump manufacturers are eager to fulfill this demand.

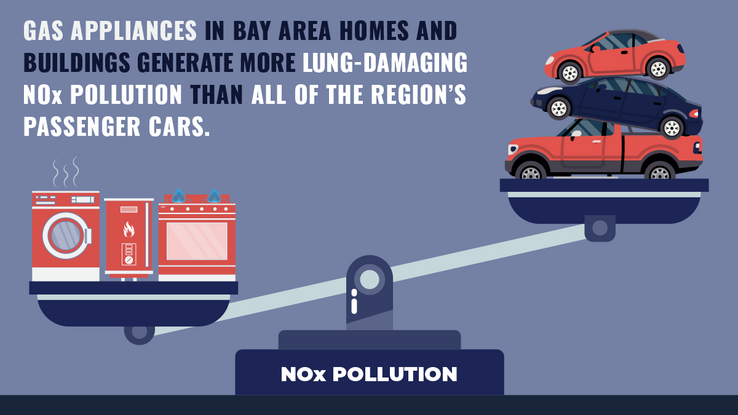

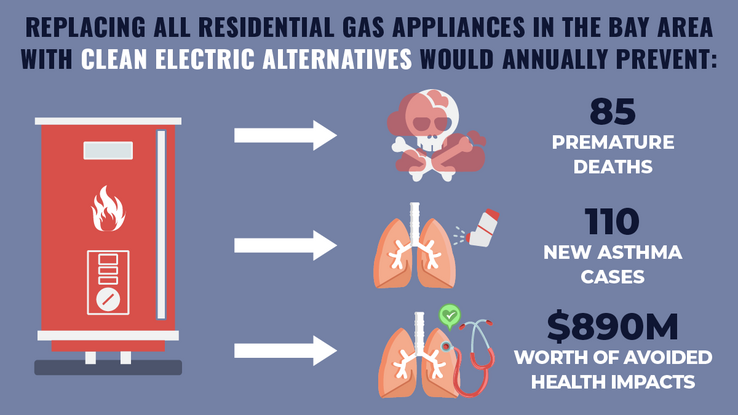

Ending fossil fuel combustion in homes and other buildings is essential to safeguarding people's health. The Bay Area’s gas-heated buildings create eight times more smog-forming nitrogen oxide (NOx) pollution than power plants and three times more NOx than passenger vehicles. Implementing the new standard is expected to help prevent 15,000 asthma attacks and avoid up to 85 premature deaths every year. The standards also make the air inside homes healthier to breathe.

But for healthy air standards for HVACs and water heaters to take off in earnest, Bay Area regulators must overcome a critical hurdle: making the switch from electric to gas appliances affordable to low-income households.

To support the Bay Area’s successful implementation of new air quality standards for heaters and HVACs, SPUR developed a report to provide a realistic estimate of what it costs to install zero-pollution equipment for low-income households and for rental homes that house low-income tenants. Our report Closing the Electrification Affordability Gap:

• Focuses on the Bay Area’s air quality standard and strategies for closing the affordability gap, defined as the cost difference between installing zero-emission equipment instead of gas equipment for low-income homeowners and for landlords of affordable units in the nine Bay Area counties.

• Outlines strategies for bringing down the cost of upgrading homes with pollution-free equipment, including avoiding unnecessary panel upgrades, leveraging the existing market for cooling, and avoiding costly gas system spending.

• Recommends concrete policy steps state and local policymakers can take to ensure that pollution-free equipment is cost-competitive with gas heating equipment, along with strategies to mitigate any impacts on low-income renters and low-cost rental housing.

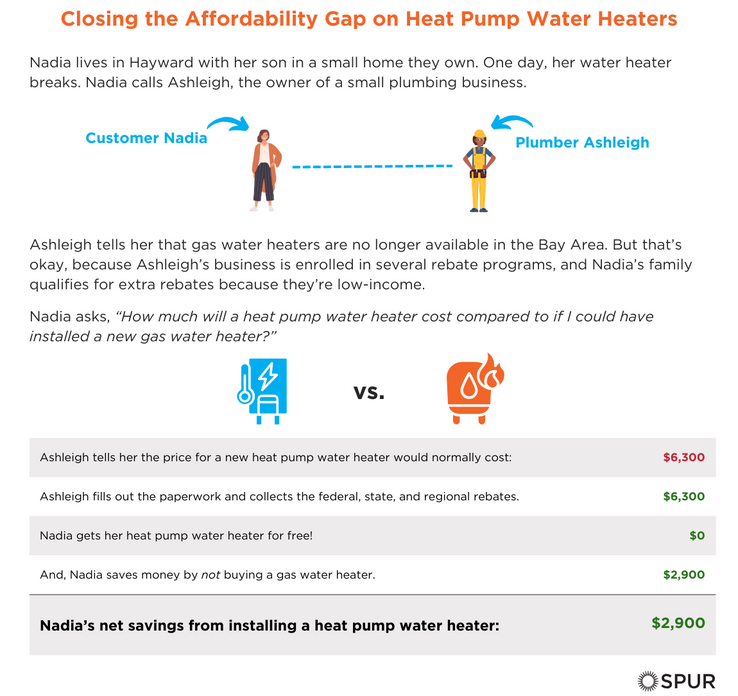

What is the affordability gap for low-income households to install heat pump water heaters?

In the current incentive landscape, every low-income household in the Bay Area can — or soon will be able to — get a heat pump water heater for FREE. In fact, low-income households would not only get a heat pump water heater for free, they would also save thousands by not purchasing a new gas water heater, resulting in a net savings of $2,900. Here’s how it works:

The question of incentive programs running out of money came to the forefront when TECH Clean California announced that 100% of the funds for PG&E customers to get heat pump water heater rebates had been reserved by February 5, 2024 — less than four months after they became available. However, 97% of the rebate money allocated for low-income households to install heat pumps remains available. Additionally, combined potential rebates from federal, state, regional, and Community Choice Aggregator sources exceed the average cost of a new heat pump water heater by hundreds or thousands of dollars. So, if any rebate goes on hiatus, installation costs for low-income households will still be covered.

Because heat pump water heaters are now or soon will be free for low-income households in the Bay Area, the region has a window of opportunity to implement the policies that will bring down the cost of heat pump installations and to develop more sustainable sources of funding so heat pump water heaters and HVACs will remain affordable as rebates gradually wind down.

What is the affordability gap for low-income households to install heat HVAC systems?

The cost for low-income households to install a heat pump HVAC system depends on where they live — specifically, on the Community Choice Aggregator (CCA) that serves their area. If they live in an area served by a CCA offering generous heat pump HVAC incentives, they will spend less on a heat pump HVAC system than a furnace, resulting in net savings. If they live in an area served by a CCA that offers less generous or no heat pump HVAC incentives, they will spend less on a gas furnace than a heat pump HVAC system, resulting in net costs. SwitchIsOn.org lets any homeowner or landlord quickly find the incentives available to them.

The Net Costs/Savings to Install a Heat Pump HVAC Unit Instead of a Gas Furnace Varies by Location

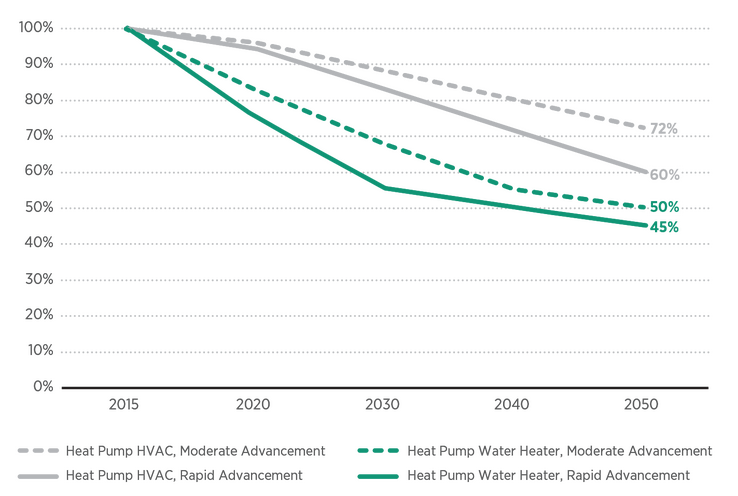

Market development is likely to reduce the price of clean heating equipment.

A National Renewable Energy Laboratory study projects that research and development funding, combined with policy and consumer choice shifts that increase heat pump demand and production, will lower costs for HVAC heat pumps and heat pump water heaters by 2050.

Installation Costs Are Predicted to Decrease

A no-regrets strategy to reduce the cost of electrification is to avoid unnecessary panel upsizing.

Upsizing a home's electric panel to accommodate electric heating equipment is one of the most time-consuming and expensive steps in electrification. Upsizing costs between $2,000 and $4,500 and requires a complex approval process with PG&E.

Most Bay Area homes can avoid panel upsizing by using optimization strategies — solutions for accommodating more electric equipment on a smaller panel. The key is getting owners and contractors to plan and right-size their equipment.

California should implement several strategies to remove the necessity for panel upgrades, including contractor education and easy-to-use tools that help homeowners pick the right zero-pollution equipment. (Watch this space for a decision support tool from SPUR and partners TRC and Build it Green). Incentive programs should also include subsidies for technologies that mitigate the need to upsize a panel. One such technology is the 120-volt heat pump water heater, which plugs into a standard outlet.

Policy changes are also needed. Policymakers should revise the national and California electrical codes to allow homes to add electrical equipment without triggering a panel or service upgrade while maintaining safety standards.

Avoiding unnecessary panel upgrades can help save California homeowners between $31 billion and $309 billion. Avoiding that work has another benefit: lightening new demands on California’s already-taxed electric grid.

The switch to electricity could save millions of homeowners from buying an expensive new air conditioner when they could buy a heat pump, which heats AND cools.

Between 2015 and 2021, some 1.72 million homes in California added air conditioning for the first time. This trend is likely to accelerate as extreme heat intensifies. For a modest increase in upfront cost, households in the market for central air conditioning can install a heat pump instead, getting themselves a brand-new heater in the bargain.

Bay Area policymakers can ensure that the transition to healthy, climate-friendly heat pumps is affordable for low-income households.

The Bay Area is home to approximately 585,000 low-income households, 40% of which are homeowners and 60% of which are renters. Making the transition to zero-pollution heating equipment affordable for homeowners requires funding and financing to cover the incremental cost of heat pumps. SPUR recommends two strategies for mitigating the cost burden of air quality standards on low-income homeowners:

- Spread the good news that ratepayers can choose electrification-friendly rate plans that will help most people save money when they switch to heat pumps.

Electricity rates should be redesigned to encourage the transition to electric heating and cooking equipment and to incentivize customers to shift their electricity use to times when the power supply is high and demand is low. The good news is that new electrification-friendly rates from PG&E mean that most single-family home customers can save money on their energy bills when they electrify. How apartment dwellers’ bills will be impacted if they sign up for electrification-friendly rates requires study.

- Increase the availability of financing options, especially those that serve the needs of households with poor credit that cannot afford the risk of taking on debt.

Low-income households benefit most from financing they repay from bill savings, so they aren't taking on an additional expense they can't afford or a loan they might default on. In inclusive utility investment financing, the utility treats appliance upgrades as utility investments, which are gradually paid by the account holder from their realized bill savings. If an account holder moves out, the new account holder takes on the repayment.

For renters, ensuring that the cost of installing zero-pollution equipment is affordable means ensuring that those costs aren’t passed on in rents, which could deplete the region’s already-scarce supply of affordable housing. The strategies differ based on housing type:

- In rent-controlled housing, landlords are already limited in the amount of capital investment they can pass on to their existing tenants. Still, they can increase rents when a new tenant moves in. Therefore, incentive programs should encourage projects that allow tenants to stay in the building or return after retrofits. These programs should cover enough of the upfront costs that the landlord still makes a profit and isn’t pushed to sell the building, thereby triggering the Ellis Act, which would allow evictions.

- In subsidized affordable housing, rent is legally limited and doesn’t change when new tenants move in. Therefore, incentive programs should cover enough upfront costs so landlords neither eat into their operations and maintenance budget nor take on excessive debt.

- For housing where rents aren’t controlled or are only subject to the statewide rent cap, incentive programs must balance the goals of safeguarding tenants and enticing landlords to participate. Landlords will sign up for incentive programs only if the programs are simple and cost-effective. Incentive programs should offer deep discounts on zero-pollution equipment so landlords can limit the costs they pass on to tenants.

Implementing the Bay Area’s air quality standards for HVAC and water heating equipment in a way that protects low-income households is absolutely possible, and much is riding on the region’s success. Policymakers must use this critical three-year window before the standards go into effect to mobilize agencies to implement cost-reduction policies, smooth the challenges households face in accessing electric equipment, and protect renters.

Read SPUR's report Closing the Electrification Affordability Gap