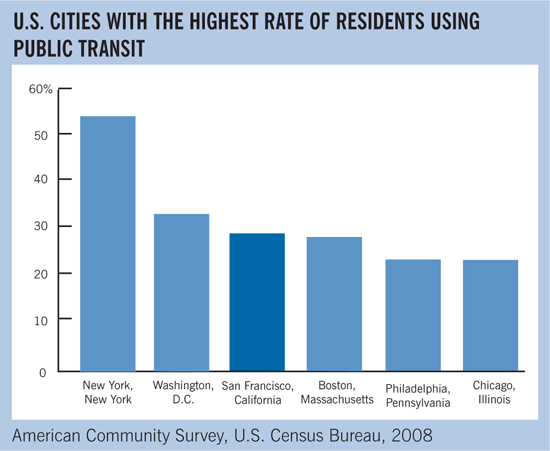

It's easy to forget all that is good about public transportation in San Francisco. Every day, the number of boardings on Muni buses and trains is nearly equivalent to the entire population of the city, and per-capita transit use is higher here than anywhere else in America but New York. One-third of local commuters take transit to work—during rush hour, fully two-fifths of trips to and from downtown are on transit—and Muni riders are more economically diverse than those on other U.S. transit systems. Atypically for an American transit system, Muni is a viable transport option for many, if not most, of the people who live and work here. In addition, it is widely used by the middle class and essential to the everyday functioning of the city.

Of course, Muni's reputation for dysfunction also is grounded in reality. It is unique among large U.S. transit systems in that the overwhelming majority of its riders must travel by bus and not train. Even Muni's light rail vehicles often mix with other street traffic, and as a result, Muni is the slowest major transit system in America—and among the least reliable and most overcrowded. In recent months, a few high-profile accidents and criminal incidents also have made headlines, although data suggest Muni hasn't actually gotten noticeably less safe.

While there are lessons both good and bad that other cities might draw from Muni and its parent organization, the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, a few recent highlights may be most noteworthy.

The Transit Effectiveness Project

The Transit Effectiveness Project is a comprehensive audit and redesign of Muni services, an effort to make the system more cost-effective by redeploying existing resources and targeting investments to better serve a majority of riders. The process of studying service and developing ideas for improvement often was contentious, and many of its final recommendations remain controversial. A time line for implementation remains uncertain, and some of its most difficult challenges, such as stop consolidation, are yet to be fully confronted. Yet the TEP has already proven its value, even if not precisely in the way it was originally intended. When the TEP was conceived, Muni was in relatively less-dire straits than it is now, though it was not precisely flush even then. The project was launched on high hopes: using exhaustive data collection and careful planning, a transit system under more or less constant siege could be made smarter and more efficient, both more financially sustainable and more useful.

It's easy to forget that before this most recent Muni crisis, the agency was making real progress. One of the TEP's most often overlooked elements was a push to fill front-line positions, including the maintenance workers necessary to ensure the consistent delivery of service day in and day out. Muni staffed up, and statistical indicators of reliability rose to their highest levels in years.

Critics always viewed the TEP as a Trojan horse for service cuts. And when Muni was confronted by a sharp downtown in its financial situation shortly after adoption of its final recommendations, those fears appeared to have been confirmed. By the agency's own admission, Muni's recent service cuts were guided by TEP recommendations. Routes 4, 7, 20, 26, 53 and 89? They never stood a chance, not after they were targeted for elimination by the TEP.

Yet less publicized among the changes were upgrades to service born of TEP recommendations: A new route (9L) serving some of the city's most impoverished neighborhoods; longer hours and more runs on the workhorse 38L-Geary; and the long-overdue conversion of the 14L-Mission from a route Muni had always considered a superfluous duplication of BART service into a fully fleshed-out line.

In the end, overall service levels weren't cut. But by taking the opportunity to redo operator schedules that hadn't been updated for years, the agency was able to save millions. The new schedules reflect growing traffic congestion—the root cause of many of Muni's troubles—and should prove more realistic and reliable. And this won't just benefit riders; it should improve operator morale.

Whenever Muni had needed to cut service before, it had cut not with a scalpel but with a cleaver. Who would notice if headways were made a minute longer on frequent routes? It hadn't seemed to matter if a minute amounted to a 10 or 20 percent reduction in service and capacity, or if the attendant increase in crowding made service less reliable and made that extra minute stretch ever longer.

And as much as Muni riders may have protested the latest service cuts, it's not hard to imagine the outrage that might have exploded if the agency had not already previewed many of the changes at dozens of public meetings during the TEP process —or if the TEP recommendations hadn't been thoroughly rethought as a result of those meetings. The TEP, whatever else it may turn out to be, has already curtailed the damage from a crushing budget deficit and could serve as a model for other transit agencies struggling with similar scenarios.

Multimodal Management of Streets

A decade after the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency was born of a citizen-mandated merger (led by SPUR) of Muni and the Department of Parking and Traffic, the SFMTA is showing signs of fulfilling the promise made to voters in 1999: that a joint agency responsible for mobility by all modes, including driving, transit, cycling and walking, could be a holistic, comprehensive and balanced manager of the city's public rights-of-way, an arbiter considerate of and fair to all users.

A recent reorganization of the agency's hierarchy offers some evidence of this new attitude. Where before there was a head traffic engineer, there is now a "director of sustainable streets." Skeptics remain skeptical, and as always, only time will tell.

But there is some evidence on the ground. To be sure, the SFMTA is but one player in the emerging Complete Streets movement, which seeks both to re-engineer streets to accommodate movements by a variety of users and to green the city's landscape. The San Francisco County Transportation Authority, the Planning Department and the Department of Public Works all bear some responsibility for the city's streets. But the partnerships the SFMTA is building as a part of these efforts are themselves signs of progress toward a more comprehensive and unified approach.

More concrete examples of this shift can be found on Market Street. The Better Market Street pilot program is a joint effort of all four agencies, and preliminary findings from its experiment in the limited diversion of Market Street traffic—major benefits for transit riders and cyclists, with only a modest impact on motorists—have been well-publicized, as has the support it has earned from business interests who were previously skeptical of changes to the city's main street. But another pilot program has received less press: the Calm the Safety Zone project, a collaboration between the MTA and SFCTA that has redesigned the areas around Muni boarding islands at Fourth and Fifth streets to better protect cyclists and pedestrians, including transit passengers.

Proof of Payment Policy

Under a "proof-of-payment" policy, transit riders who've already paid for their trips can board buses and trains through any open door, without lining up and stopping in front to pay or display passes or transfers to drivers. This speeds up the loading and unloading process.

Muni's long journey toward a systemwide proof-of-payment policy—a move that now seems inevitable, though the timing of its implementation remains unclear—has been going on much longer than many people realize. The agency first implemented POP on the platforms of its new Stonestown and San Francisco State University Muni Metro stations in 1993. POP throughout the Metro network followed some years later, and some years after that, Muni threw its weight into a genuine enforcement effort to ensure riders were actually paying.

But Muni planners understand the value of such a system. The agency's recent Proof-of-Payment study found that while Muni was losing millions of dollars annually to freeloaders boarding through back doors, a de facto policy of all-door boarding on busy bus lines has reduced the time vehicles spend stopped and loading and unloading passengers. It also has contributed to productivity that is literally off the charts: an average of nearly 70 boardings per hour on Muni buses, a figure higher even than rates in New York, Los Angeles or Chicago.

The same study also found that while the systemwide fare evasion rate was nearly 10 percent, on Muni Metro—where a formal POP policy is in place, including fare inspection—it was less than 5 percent.

Real-Time Data Availability

After a dispute in summer 2009, the SFMTA took steps to put its real-time arrival data in the public domain.

Image: flickr user Jamison

The Bay Area may lay claim to the world's most tech-adept populace, but government agencies haven't always been early adopters. While BART has made a name for itself as an industry leader in making available real-time data on vehicle locations (for example, announcements of "next arrivals in 5 and 15 minutes") for third-party developers of mobile applications, until recently Muni seemed consigned to the 20th century.

That changed in November when the agency took an important step toward opening up its data for use by outside software developers by publishing the NextMuni real-time arrival data stream on its web site in the popular XML format. XML has become a standard format for a diversity of applications, so Muni's move is a nod to developers that ultimately should prove a boon for riders, who stand to benefit from a wider range of more robust choices among arrival-time applications. These applications not only can display arrival times, but also allow users to customize them according to their own needs, by entering favorite stops or simply calling up nearby stops automatically.

But progress toward opening up Muni's information hasn't been without its bumps. Over the summer of 2009, a dispute played out between the developer of Routesy, one of two iPhone applications repackaging NextMuni data, and a company called Next Bus Information Systems, which claimed the data as proprietary. Routesy was temporarily removed from Apple's iPhone App Store, and tech-reliant Muni riders cried foul.

Other transit agencies might have ignored the fracas—or worse, taken the position that open-sourcing would compromise control. Instead, Muni not only took Routesy's side in the dispute, but inserted a clause in a renegotiated contract with NextMuni stipulating that the company must help it make the data public. NextMuni, for its part, has publicly supported release of the data.

The NextMuni system itself took years to roll out, and Muni was subjected to much criticism. Others might dismiss the notion that an important part of a transit agency's mission is providing arrival-time info to disproportionately white and wealthy smart-phone users. Yet there is little if any downside for the agency in making it possible for others to make the system more user-friendly.

Ultimately, if there is one lesson to be learned from Muni, it might be one that has little to do with the agency itself: Land use and urban design really do matter. Making Muni faster, more reliable and capable of carrying more passengers—by way of rail and bus rapid transit projects, or through the less expensive measures recommended by the TEP —will make it more attractive to riders. But for all of Muni's problems, ridership is already remarkably high. Muni's busiest corridor, Geary, is served exclusively by buses—relatively slow, unreliable and overcrowded buses. Yet San Franciscans ride Muni because San Francisco is a city that was built for transit. In recent decades, as San Francisco has become more accommodating of automobiles, Muni ridership has declined somewhat. And San Franciscans love to complain about Muni service, rightly so in many cases. Nevertheless Muni offers proof that supportive land uses and a walkable environment can drive transit use, even where transit service suffers from a lack of political and financial support.