Parking spaces are expensive to build, especially where land values are high. Typically, a parking space adds $25,000 to $50,000 or more to the construction cost of a new housing unit in San Francisco. If we can find a way to build less parking, we will see both lowered housing prices and more efficient use of urban land for the city as a whole.

In every American city, vehicle ownership has increased more than population over the last several decades. The dilemma of how to deal with our cars confronts all cities with greater urgency as each year goes by. In San Francisco, where the 19th century street grid puts absolute physical constraints on the ability of people to move around by car, we have made a virtue of necessity and decided to promote a Transit First policy. SPUR in fact first proposed the Transit First policy in 1972. It was adopted by the City the next year and ultimately placed in the City Charter in 1996. This policy is one of the major reasons that San Francisco has retained so much of its historic fabric and pedestrian friendliness. Given the conflict between maintaining our compact, Transit First city and our society's increasing dependence on the automobile, we have no choice but to work out a compromise.

There is a lot at stake on our decisions about parking, in addition to the cost of housing. If we increase the amount of urban real estate we devote to our parking needs, we push activities farther away from each other, thereby making it even harder for people to walk where they need to go. Increased parking becomes a vicous circle, where the more parking we build, the more people have no choice but to drive. Access-by-proximity, the great advantage that belongs to city dwellers, depends on a compact, intimate mingling of people and land uses. We cannot simultaneously provide parking spaces for each person at each destination and still be a city that enjoys access by proximity.

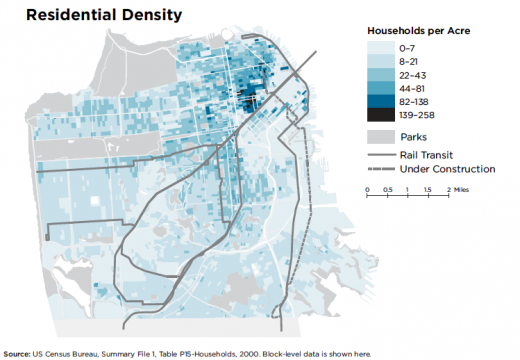

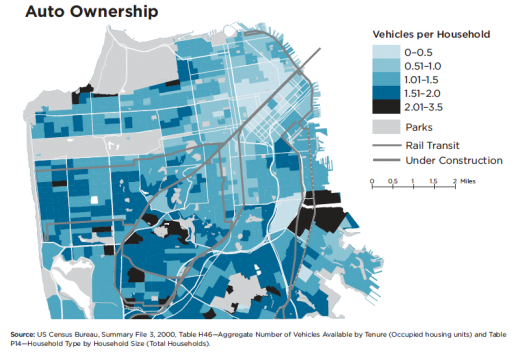

Higher residential densities allow people to own fewer cars.

When we talk about the ability to get around without a car, we are getting near the heart of what makes San Francisco different from most other American cities. San Francisco's urban form is compact rather than spread out, human scaled rather than highway scaled. Even after these many decades of increasing car orientation, we are still a city where people can live their lives without cars. Consider some of the following numbers, based on 2000 census data:

- Fewer than 40 percent of San Francisco residents commute to work in a single-occupancy vehicle.

- Twenty-nine percent of San Francisco households don't have a car and 42 percent have just one.

- In the most compact, walkable neighborhoods, auto ownership rates are less than 0.5 autos per household.

Our policy and urban design decisions today will determine the way future generations of San Franciscans live. If, over time, we remake our city to accommodate cars at the expense of walking- and transit-oriented environments, people who live here will drive more. If, over time, we create more pedestrian-accessible land uses and invest in our transit system, people will drive less.

SPUR recommends reducing parking requirements in certain locations and under certain conditions. These recommendations would lower housing costs, increase housing production, and improve San Francisco's quality of life by:

- Promoting more efficient use of our limited land by allocating more space on a given lot for housing and less for automobiles

- Allowing residents to choose to forego the costs of having a parking space

- Making it easier for people to use cars when they need them, without having to own (and park) their own car

- Making the approval process for transit-friendly housing developments more predictable.

SPUR recommends seven policy and Planning Code changes that promise to either rationalize or reduce a portion of housing costs associated with parking.

- Reduce minimum parking requirements for housing that serves populations that do not have a high frequency of car ownership.

- Encourage residential developers to build and market parking seperately from the dwelling unit, thereby "unbundling" the cost of parking from the costs of the unit and reducing parking requirements.

- Encourage convenient pay-per-use automobile services such as car sharing.

- Reduce minimum parking requirements for housing that serves populations, such as seniors and low-income households, that do not have a high frequency of car ownership.

- Waive off-street parking requirements when a new curb cut would take away as many on-street spaces as the private parking spaces it would create.

- For historic buildings, allow exemptions from new off-street parking requirements triggered by a change in use or occupancy.

- Adjust the Planning Code's parking-space-size requrements to conform to the Department of Parking and Traffic's size requirements and to allow for a greater proportion of compact parking spaces.

It should be clear that these housing policies must go hand-in-hand with appropriate transit policies, both locally and regionally. The ability of people to live without daily use of cars depends on a well-functioning transit system and on good land use-transportation coordination. In this paper, we confine ourselves to a discussion about residential parking requirements as an aspect of San Francisco's housing policy, but our goals of reduced auto dependency and lowered housing costs can only be achieved by simultaneously increasing our local and regional investments in transit and other mobility options.

1. Reduce Minimum Residential Parking Requirements in Neighborhoods Where It Is Convenient for People to Get Around Without a Car.

It is the policy of San Francisco to cluster higher-intensity land uses such as dense residential developments near major transit lines. In areas that are well-served by transit and which are located near local retail services, can San Francisco define a set of "Transit-Intensive Areas" in the Planning Code and reduce the minimum parking requirements in these areas?

It almost goes without saying that when people find it easy to get around without a car, they drive less and tend to own fewer cars. San Francisco neighborhoods range in their auto ownership rates from under 0.5 per household to more than 1.5 per household.

Perhaps we can find a way to pay attention to this difference, rather than treating all locations the same with respect to their parking requirements. In neighborhoods that are walkable and close to major transit lines, can we reduce, or perhaps eliminate altogether, the minimum parking requirement for new residential construction?

"Transit-Intensive Areas" are defined by two characteristics: They have commercial districts (so residents can walk for many daily errands) and they lie on major transit lines (so residents have easy transit access to destinations throughout the city and region). For the purpose of amending the Planning Code, Transit-Intensive Areas would need to be rigorously defined. As a starting place, SPUR suggests that any area that meets the following criteria be considered a Transit-Intensive Area:

- Any area within 1,200 feet of a Transit Center (as defined in the General Plan); 1,200 feet is slightly less than a five-minute walk at a slow pace.

- Any area within 1,200 feet of the overlap between a transit corridor and a commercial or mixed use district (transit corridors are herein defined as the General Plan's Transit Preferential Streets or Rail Lines; commercial and mixed use districts are defined in the Planning Code)

- Any area within the Downtown Parking Belt (an area within downtown designated by the General Plan as having only short-term parking)

These neighborhoods are great urban locations, filled with human activity and scaled to pedestrian use. They are the kind of neighborhoods that evolved historically in San Francisco. In areas such as these, where the infrastructure is in place to provide good transit and pedestrian amenities, it makes sense to give housing developers the flexibility to provide less parking.

In order to make this work, we would need to address the issue of on-street parking, meaning the problem of "parking spillover" where people who don't have their own off-street parking space would crowd the on-street spaces. One way of solving this would be to make the Transit-Intensive Areas into residential parking permit zones. It might even be possible to charge market rates for any non-permit holders to park on the street, and to use the monies for neighborhood improvements. If a Transit-Intensive Area were a parking permit zone, the Planning Commission would have a tool at its disposal for helping to fit new developments into existing neighborhoods: As a condition of approval, the Commission could make residents of new units that do not come with parking spaces ineligible for parking permits. A person who would choose to live in a unit created under this new provision would benefit from the lowered cost of housing and simply would not be allowed to park on the street for extended periods.

As San Francisco adds to its transit system over time, new neighborhoods would come under the Transit-Intensive designation, and the parking requirements could be adjusted accordingly. The goal would be to enhance neighborhood character and walkability, which means that the specific design solutions would need to be tailored to each unique neighborhood.

2. Encourage Residential Developers to Build and Market Parking Seperately From the Dwelling Unity, Thereby "Unbundling" the Cost of Parking. PARTIALLY UNDERWAY.

Some of the costs associated with automobile ownership are hidden in that they are inseparably bundled with something else. A "free" parking space which comes with a home, workplace, or shopping center is not really free at all. The cost is just bundled into the cost of the house, the employer's overhead or the retailer's fixed operating costs.

A 1997 study for the San Francisco Planning Department (using 1996 data on housing prices) found that housing units without parking spaces were significantly more affordable and sold significantly more quickly than those with a parking space. On average, the value of an off-street parking space for a single family home was $46,391; for a condominium unit the value was $38,804. Approximately 20 percent more San Francisco households could qualify for mortgages for units without off-street parking than can qualify for units with parking. Most importantly, for people who wonder how great the demand is for housing without parking, single family units without parking sold five days faster and condominium units without parking sold 40 days faster.

Our knowledge of market economics tells us that when the true costs of parking are made visible in the rental or purchase transaction, we can expect that some people will opt to forego the cost of a parking space. Bundling parking spaces into the cost of housing artificially increases car ownership rates because it prevents the proper functioning of a market for parking. If we made the added cost of providing parking explicit in the transaction between developer and owner or between owner and renter, the market would determine how high the demand for parking really is for each location. This could be done by creating parking "units" on a separate deeded or leased parcel.

Ideally, this pattern would sometimes encourage multiple developers on the same block to combine their parking units into one structure. While this would devote a piece of land to a parking garage—not always a desirable goal—it would have the benefit of using city land more efficiently and lowering the construction cost of housing by agglomerating parking into one location. As a significant side benefit, it would reduce the number of curb cuts encroaching onto the sidewalk.

Based on the expectation that residents who do not need parking will choose not to purchase it, the Planning Department should conduct a study to determine the proper reduction in parking requirements when parking is provided as a separate parcel. We stress that these would be reductions in the minimum parking requirements; more parking could still be constructed according to the developer's understanding of market conditions.

As a related measure, we should amend the Planning Code to allow the lease and sale of parking spaces to off-site residents. While this practice takes place "under the table" today, it should be encouraged as part of the creation of a true market for parking.

STATUS: Since we first brought up this idea of unbundling parking spaces from the dwelling unit, it has become increasingly common practice among developers of new housing. This has happened through either market forces or project-specific negotiations with the Planning Department. We expect this idea to be adopted as a development regulation on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood basis over the next several years.

3. Encourage Pay-Per-Use Car Services Such As Car-Sharing. DONE.

Car-sharing is a service that makes cars available to people by the hour, allowing residents and businesses to use a car whenever they need one without having to pay the costs of owning, insuring, maintaining, and parking one.

Car-sharing organizations reduce over-dependency on cars, while still providing access to them when needed. Economists have long pointed out that individual car ownership encourages over-reliance on the automobile because so many of the costs are fixed costs. Insurance, financing, and registration are paid up-front, and are constant, no matter how much or how little one drives. Car-sharing converts these costs into a variable time and mileage charge, so that people pay based on the amount they drive. When the fixed costs of car-ownership are made visible in each use of the vehicle, people have been shown to switch many of their trips to foot, bike, or transit, using a car only when it is truly "worth it."

The idea holds great promise as part of the solution to the parking dilemma for urban areas such as San Francisco. Here, where people have excellent access-by-proximity, there is literally not enough space for everyone to have a dedicated personal parking space at home and at work. By making more intensive use of each car (and each parking space), City CarShare is reducing the total number of vehicles that need to be stored in San Francisco. The results so far show that every car added to City CarShare's fleet translates into six cars being sold.

To make sure that car-sharing actually translates into more affordable housing, the City should change the Planning Code to allow developers to build fewer parking spaces if they provide access to a shared fleet of vehicles. This shared fleet could be provided through a car-sharing service, an on-site rental car agency, or a car “concierge” to an off-site location. For residential construction, the City should reduce the current parking requirement of one space for every one unit to one space for up to every four units if the developer commits to provide access to a shared fleet of vehicles. In addition, provision of car-sharing could be used as one criteria for granting conditional use permits to developments over a certain size.

As with many of the recommendations in this paper, this one depends on the ability of the City to develop appropriate enforcement mechanisms. We would suggest that the Planning Department, as a condition of project approval, could require the

developer to demonstrate the continued presence of a car-sharing service on an annual basis, to ensure that some form of car-sharing is provided in perpetuity.

Amending the Planning Code in this way would not force developers to build less parking. Rather, it would give more flexibility to developers who are willing

to work with the city to find creative solutions to San Francisco’s parking problems.

STATUS: Since this report first appeared, City CarShare has gone from concept to reality and is now providing service to thousands of households and businesses. Many housing developments include car-sharing as an amenity. Legislation to codify the trade-off between car-sharing and parking requirements has been drafted and, as of this writing, is making its way through the political process.

4. Reduce Minimum Parking Requirements for Housing That Serves Populations That Do Not Have a High Frequency of Car Ownership. PARTIALLY IMPLEMENTED.

Some housing types primarily or exclusively serve populations which have very low utilization of private vehicles. Parking requirements increase the costs or subsidy of these units and provide little value to the residents. SPUR believes that minimum parking requirements should be eliminated altogether for two specific types of housing:

- 100 percent affordable developments, in which every dollar spent building parking is a dollar not available to build another affordable unit

- Single Resident Occupancy (SRO) units, which are only allowed in the areas with great transit and stores, and which serve populations that cannot afford cars

This does not mean that the nonprofit agencies that build these types of housing would be prevented from building parking; it means that the City would not force them to build it, leaving the number of parking spaces up to their professional judgment about the client base they serve. In a city with the kind of homeless problem that San Francisco has, it simply does not make sense to have laws that require us to spend what little affordable housing money we have building parking spaces that will sit empty.

STATUS: As with the previous recommendation, the legislation to implement this idea is in the works.

5. Waive Off-Street Parking Requirements When the Curb Cut Would Take Away as Many On-Street Spaces as the Private Parking Spaces it Would Create.

Often in districts with lower residential densities, the creation of new off-street parking spaces takes away an equal number of on-street parking spaces. From the perspective of the neighborhood as a whole, there has been no net gain in parking, but the curb cuts have increased potential hazards for pedestrians and reduced retail continuity in commercial districts.

It can easily cost between $20,000 and $50,000 or more to create an off-street space as part of a residential remodel. Where the presently required creation of a new off-street space would be directly cancelled out by the removal of an on-street space, the property owner should have the choice not to build the parking space.

There is already a precedent for this approach in the provision in the Planning Code in the Bernal Heights Special District, which allows for the administrative reduction of parking requirements that are triggered by building enlargements if it can be shown that the imposition of the requirements would cause a loss of on-street spaces. This policy should be expanded to all residential districts.

In commercial districts, new curb cuts and garage entries also reduce pedestrian safety and disrupt retail continuity. To prevent this impact, off-street parking requirements for buildings on commercial streets should be able to be modified if the imposition of the full requirements would create such negative impacts. Residents living above commercial uses are less likely to need cars for shopping, so there is an additional logic to allowing for the reduction of parking in mixed use areas.

In both cases, the appropriate mechanism for evaluating the reductions would be a zoning administrative modification.

6. For Historic Buildings, Allow Exemptions From New Off-Street Parking Requirements Triggered by a Change in Use or Occupancy.

Owners of historic buildings face a lot of challenges. Parking requirements don't have to be one of them. San Francisco should waive parking requirements for these buildings both as a bonus to people who maintain our architectural heritage and as a way to protect historic character from the incursion of new parking garages.

The issue arises only when a change in use or occupancy would normally trigger increased parking requirements. For buildings that are listed as historic (or eligible for listing), or buildings that are contributory to landmark districts, there should be no required increases in parking for use or occupancy changes, provided the changes are certified as appropriate by the Landmarks Preservation Advisory Board.

7. Adjust the Planning Code's Parking Space Size Requirements to Conform to the Department of Parking and Traffic's Size Requirements and Allow for a Greater Proportion of Compact Parking Spaces.

The Planning Code says that regular off-street parking spaces must have a minimum area of 160 square feet and "compact" spaces must have a minimum area of 127.5 square feet.

The Department of Parking and Traffic defines the minimum dimensions of a parking space as 8 feet by 18 feet for a standard space (equivalent to 144 square feet) and 15 feet by 7 1/2 feet for a compact space (equivalent to 112.5 square feet).

SPUR recommends changing the Planning Code to use DPT's measurements.

In addition, the Planning Code currently allows one out of every four parking spaces to be compact. In San Francisco as a whole, supporting the use of small vehicles is one of the most obvious ways to strike a reasonable compromise with the automobile. And in fact, even with the recent proliferation of large "sport utility vehicles," the average San Francisco car is not as long as cars were several decades ago, when the codes were written. Both out of recognition of the fact of smaller cars and out of the need to encourage them, SPUR recommends changing the Planning Code to allow one out of every two spaces to be built to compact dimensions, for any structure for which two or more spaces are required.

Current guidelines allow 100 percent of parking spaces in the South of Market district to be compact. This is a good precedent. We recommed either allowing larger numbers of spaces in the rest of the city to be compact, or, better yet, removing this regulation from the Code entirely and letting the size of parking spaces be a market decision. There does not seem to be a compelling public interest in policing the size of the parking spaces that developers build.

We cannot fit high numbers of additional cars into San Francisco. If we design our city along suburban lines, where we construct a parking space for every person, at every destination, San Francisco's walkable streetscape will be compromised and the intensity of activities—the very definition of urbanity—will decrease. It will also become increasingly difficult to get around, as traffic slows down not only cars, but also blocks the way for bikes and transit. If we want to evolve in a way that builds on our urban strengths, it is in our best interest to limit the amount of parking we construct, and simultaneously, to invest heavily in our transit, bicycle, and pedestrian infrastructure.

Our relative independence from cars can be leveraged into a way to make living in San Francisco more affordable. Re-thinking our parking requirements as suggested in this paper would lower the cost of housing by:

- Making available new housing without parking, for people who would choose to forego a car in order to bring down their housing costs

- Fitting in more housing on a given lot size, by trading garage space for living space

- Allowing people to utilize car-sharing as a cheaper, more convenient alternative to private ownership

- Providing more certainty in the approval process for new housing developments that try to take full advantage of San Francisco's transit and pedestrian accessibility.

Through changing our parking requirements along these lines, San Francisco can build more housing while reinforcing the city's unique urban strengths so that, over time, it will grow more pedestrian-friendly, more transit-rich, more environmentally-sustainable, and more affordable.

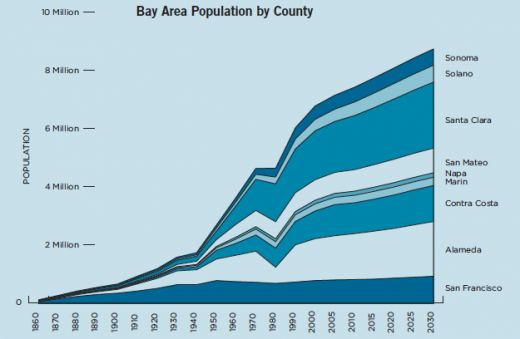

APPENDIX I: The Housing Crisis in Regional Perspective

The Bay Area does not produce enough housing for the jobs it creates. This “jobs/housing imbalance” is one of the fundamental causes of San Francisco’s housing crisis. Between 1990 and 2000, the Bay Area added 548,000 jobs, but only 220,000 housing units—just 60 percent of the housing supply needed to keep housing costs level with inflation.

Economic projections show more than a million new jobs being created in the region over the next 20 years. This is what fuels population growth. People are moving to the Bay Area for high-paying jobs. The question is, where will all these people live?

From a regional environmental perspective, the projected population growth is troubling because if the majority of these new residents live at suburban densities, the population growth will consume vast amounts of open space and will place people in locations that are car-dependent. Planners know that the most important way to reduce America’s ecological footprint is to reorganize our settlement patterns into tight urban clusters instead of suburban sprawl. The pedestrian- and transit-oriented city is both ecologically and socially more desirable. There is an environmental imperative to channel as much of the region’s

growth as possible into the central cities: San Jose, Oakland, and San Francisco.

For every person forced out of the city by the lack of housing and forced to live on the periphery of the Bay Area, we make the region’s problems worse. Sprawl development consumes enormous resources in land and infrastructure while forcing residents to drive for every trip. San Francisco, because of its unique urban character, is the best equipped place in the region to support density. Our housing policies have a regional—and a global—responsibility to accommodate a greater share of the region’s growth.

But we can also expect that large numbers of these new residents will want to live in San Francisco. The qualities current residents love about San Francisco—beauty, walkability, urbanity, cultural tolerance, diversity—are likely to appeal to newcomers to the region as well. This, in a nutshell, is why there is such a large demand to live in San Francisco. This is the problem that our housing policies must solve.

We cannot stop regional population growth. But what would happen if we “pull up the drawbridge” into the city by not building housing for the people who want to live here? The answer is clear: We will preserve the existing built fabric of the city, but at the expense of dramatic cultural displacement. We will force people to compete with each other to live here, so that only the most economically-successful will be able to stay. This, in essence, has been the strategy of carefully-protected enclave cities like Carmel, California and Boulder, Colorado.

San Francisco’s only chance to hold onto its cultural diversity coincides with the ecologically responsible path: Build substantially more housing, both market rate and subsidized affordable.

We know the region as a whole will continue to grow, but we don’t know where exactly the growth will be. SPUR is one of many organizations in the region working to direct population and job growth into existing urban areas, hopefully near transit. The alternative is to continue to export our housing demand onto farmland in the Central Valley and force people to commute hours each way.

Source: Association of Bay Area Governments, ABAG Projections 2005, http://data.abag.ca.gov/p2005/regional.htm; Association of Bay Area Governments, “Population by County, 1860–2000,” http://census.abag.ca.gov/historical/copop18602000.htm

APPENDIX II: The Role of State Government in Solving the Housing Crisis

This report talks about policy changes within the control of the City and County of San Francisco. However, it’s important to remember the broader context of problems that require changes at a higher jurisdiction. Many of the tools that would help us solve the housing crisis require action at the state level.

Fiscalization of land use. Since Proposition 13 reduced the ability of California cities to raise money through property taxes, cities have found that housing “doesn’t pay.” From a fiscal perspective, City and County governments gain more revenues with fewer costs if they attract retail or office development instead of housing. This fact has created a dynamic in which cities compete with one another for sales tax revenue, each city hoping to gain the sales tax generated by people who live somewhere else. There is an obvious solution: Shift some of the property tax that goes to the state back to the local level and shift some of the sales tax back up to the state level as a way to level the playing field between housing and other land uses.

CEQA. The California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), passed in 1970, is a critical piece of legislation for the protection of the State’s natural environment. But there are some unintended consequences of CEQA that have the effect of discouraging infill housing and, ironically, of pushing development onto undeveloped land at the metropolitan edge. As CEQA has come to be used in the planning process, it typically treats the most environmentally sustainable projects—such as a high-density infill housing development near transit with limited parking—as potentially having negative “environmental impacts.” CEQA is used to stop, delay, or shrink housing projects, even when the projects are in the most environmentally appropriate locations. CEQA should be better integrated with planning policies and land conservation strategies. so that a comprehensive planning process, not litigation over environmental laws, guides the evolution of California’s cities and towns.

Lack of regional planning. Because California has weak regional planning laws, it is very difficult for the nine counties of the Bay Area to get together to solve common problems such as the jobs/housing imbalance. Now that Bay Area jobs are starting to be filled by people who live outside the Bay Area (for example, in the Central Valley), the need for the state to play an active role in supporting regional planning will become even more acute. Many creative ideas have been proposed short of a true “regional government.” For example, state and regional funding for infrastructure (such as transit, roads or water treatment) could be directed to places with compact, pedestrian-oriented local zoning, and away from sprawl.

Lack of political support for the Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD). The State of California has a housing department one of whose functions is to encourage planning and other activities which can increase the supply and quality of housing. Over the years, the department, through a variety of administrative and budgetary constraints, has been unable to meet this and its other mandates. Such inaction is traceable to a lack of commitment to the goals of the department by the Legislature and the Governor’s office. The department is explicitly directed to prepare a statewide housing element which contains housing goals for the following year and for five years ahead, analyze state and local housing markets and constraints, and present recommendations which will contribute to attainment of statewide housing goals. This has rarely been done except for the very early years of the department’s existence. The Department of Housing and Community Development should be empowered to take more state leadership on planning issues.

Lack of enforcement of affordable housing legislation. There are several mandates in State housing legislation that require local governments to provide density bonuses for low- and very low-cost housing projects. These are quite specific and enforceable by the State Attorney General where local governments do not adhere to them. Local governments are also statutorily unable to disapprove affordable housing projects in the absence of specific findings which must be made. Although there are many instances where such disapproval has occurred, project proponents are unwilling to pursue litigation; hence, it is up to the state to enforce such statutes.

One option to improve enforcement would be to follow Massachusetts' lead and establish a state-level zoning board of appeals. Under the Massachusetts "40B" legislation, developers can appeal directly to the state board of appeals if their permit is denied by a local jurisdiction that fails to meet a statewide affordability target (in this case a minimum of 10 percent of the local housing stock must be targeted to low or moderate households). Developments seeking appeal must meet minimum affordability thresholds: either 25 percent of units must be affordable to households earning 80 percent of Area Median Income or below or 20 percent of usnits must be affordable to households earning 50 percent of Area Median Income or below. Currently the California courts are not authorized to issue building permits if a local jursidcition unlawfully disproves an affordable housing development. The establishment of a statewide zoning board of appeals would help strengthen affordable housing legislation enforcement.