San Franciscans face hard choices at the Port. Compared to the Ferry Building and other recently completed high-profile projects, the future challenges facing the Port are far more formidable, and time is not on the Port's side. The costs of repairing, seismically upgrading and redeveloping the Port's iconic but rapidly deteriorating finger piers are staggering. Significant public investment above and beyond what could be generated from proposed development will be needed, and sources of funding will have to be found. Painful priorities will have to be set because of limited funds. The numerous regulations to which the Port is subject, including the City's own Proposition H, will have to be revisited if there is to be real revitalization. Hard choices will have to be made - and made soon.

Pier 36 in South Beach is a blighted facility along the beautiful Embarcadero Roadway.

Since the 1970s, the Port has lost 15 of these historic finger piers.

Instead of the bustling harbor that once characterized San Francisco, today's Port is a collection of underused, aging and deteriorating maritime facilities that separate the city from the Bay. Nevertheless, as some of the recently completed projects along the Northern Waterfront have shown, these same facilities provide unparalleled opportunities for reuniting the city with its waterfront. Sensitive and sensible development along the waterfront could vastly increase both open space and public access to the Bay, while contributing to the economic vitality of the city and producing the world-class waterfront all San Franciscans want. But it won't be easy. City and state plans set forth a vision for reconnecting the city with the Bay. They call for adaptive reuse of the Port's historic finger piers and other structures with a mix of commercial and maritime uses, connected by a series of waterfront open spaces and view corridors to the Bay. While this is a compelling vision, it is increasingly elusive given the physical, regulatory, financial and transportation constraints under which the Port operates.

Nevertheless, there is no turning back. The Port has embarked on a transition from its largely industrial past to a future that maintains maritime industrial uses in smaller, more compact areas along the waterfront, making way for mixed uses and exciting new recreational opportunities along the water's edge.

In this report, SPUR details the physical, regulatory, fiscal and transportation challenges the Port faces, then presents a palette of possible solutions for public consideration. There is no panacea, no single solution that will revitalize the city's waterfront. Rather, solutions will require the diligent, concerted efforts of the City, the Port, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, the State Lands Commission and the public.

Introduction

Completed high-profile projects - including AT&T Park, the renovation of the Ferry Building, Pier 1, Piers 1½-3-5 and Rincon Park - have transformed the city's Northern Waterfront from a dismal elevated-freeway corridor into one of the nation's outstanding urban waterfronts. But compared to the Ferry Building and other recent projects, the future challenges facing the Port are far more formidable, and time is not on the Port's side.

The costs of repairing, seismically upgrading, and redeveloping the Port's iconic but rapidly deteriorating finger piers are daunting, to say nothing of the hundreds of millions of dollars in other pressing needs the Port has identified in its 10-year Capital Plan, published in 2006. Significant public investment above and beyond what can be generated from proposed development will be needed, and sources of funding will have to be found. Tough decisions will have to be made about whether and to what extent historic pier structures can be saved along the Northern Waterfront. Difficult access and parking questions on The Embarcadero will have to be addressed. Painful priorities will have to be set because of limited funds.

The numerous regulations to which the Port is subject, including the City's own Proposition H, will have to be revisited if there is to be true revitalization. But even if all these regulatory constraints disappeared, it would not be possible for private development to absorb the enormous expense of rehabilitating Port development sites, while producing development even remotely acceptable to the people of San Francisco and the State of California, for whom the City and the Port hold the waterfront in trust.1 Hard choices will have to be made - and made soon.

Fronting on one of the world's great natural harbors, San Francisco has been a maritime city since its founding. For almost 200 years, in peace and in war, the city has defined itself in terms of its relation to the sea. San Francisco Bay has also provided the city with a physical setting that few other cities, if any, can match.

Today, the Port enjoys the most diverse maritime portfolio of any port in California. It provides a key stopping point for cruise vessels along the West Coast, burgeoning ferry service across the Bay, ship repair in the largest floating drydock on the west coast of the Americas, and in its Southern Waterfront, significant breakbulk and bulk shipping terminals and sand and gravel processing. In the last four decades, however, changes in shipping technology along with direct access to intercontinental rail have led to the relocation of container activity to the East Bay. The bustling harbor that once characterized San Francisco has been largely replaced by underused, aging, and deteriorating maritime facilities that separate the city from the Bay.

But as some of the recently completed projects along the Northern and Central Waterfront have shown, these same facilities provide unparalleled opportunities for reuniting the City with its waterfront. These recent, high-profile projects represent only a fraction of the vast and largely untapped potential for redevelopment and public access on Port-owned waterfront property.

Behind the imposing bulkhead buildings along The Embarcadero lie more than a dozen historic finger piers, long off-limits to the public, that offer unparalleled views of the Bay. And at Pier 70 near Potrero Hill, the Port owns a property large enough to support a new city neighborhood and containing the most important collection of historic industrial buildings in the western United States. Sensitive and sensible development along the waterfront could vastly increase both open space and public access to the Bay, while contributing to the economic vitality of the City and producing the high-quality waterfront all San Franciscans want.

But it won't be easy. Though the City gained title to Port property in 1969, it wasn't until 2000 that the city, the Port, the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission and San Francisco citizens finally arrived at a common agreement and blueprint for change, reflected in the Port's Waterfront Land Use Plan and BCDC's San Francisco Waterfront Special Area Plan. These plans set forth a vision for reconnecting the City with the Bay. They call for adaptive reuse of the Port's historic finger piers and other structures, with a mix of commercial and maritime uses, connected by a series of waterfront open spaces and view corridors to the Bay. The vision they present, while compelling, is increasingly elusive given the physical, regulatory, financial and transportation constraints under which the Port operates.

Nevertheless, there is no turning back. The Port has embarked on a transition from its largely industrial past to a future that maintains maritime industrial uses in smaller, more compact areas along the waterfront, making way for mixed uses and exciting new recreational opportunities along the water's edge. This transition gives rise to some critical questions:

How should San Francisco relate to its waterfront? How much should we invest in the shoreline, and who should contribute? How do we align the policy goals of the City and the state? Are all of the historic finger piers worth saving, and what is the best way to reuse them? What should we do in the event of an earthquake or if sea levels continue to rise?

Answering these questions will require San Franciscans, as the stewards of the waterfront for the people of California, to make difficult choices. In this report, SPUR details the physical, regulatory, fiscal and transportation challenges the Port faces, followed by a palette of possible solutions for public consideration. There is no panacea, no single solution that will revitalize the city's waterfront. Rather, solutions will require the diligent, concerted efforts of the City, the Port, BCDC, the State Lands Commission and the public.

The Port's failing infrastructure

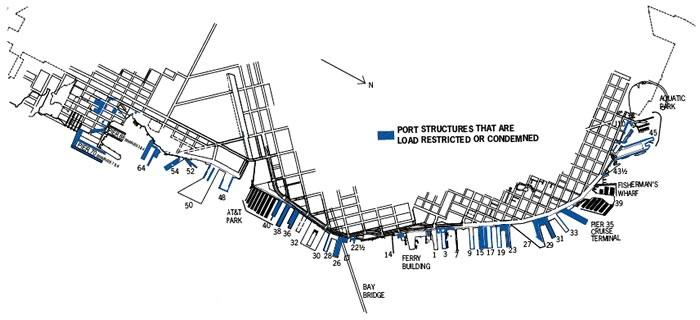

The Port holds a diverse property portfolio covering some 600 acres that extend 7.5 miles along the shoreline. Its holdings include 39 piers and wharves over water, 43 inland parcels (called "seawall lots"), and 245 commercial and industrial buildings that together comprise some 20 million square feet of buildings; miles of streets, sidewalks and utilities; and large capital assets such as maritime dry docks, cargo cranes and heavy equipment.

Even under the best of circumstances, a portfolio of this size would be a challenge to maintain. But the advanced age of many Port structures (often approaching a century), a history of deferred maintenance, and the punishing effects of wind and waves have caused much of the Port to decline into a dire state of disrepair. While the Port sustained manageable damage during 1989's Loma Prieta earthquake, the condition of the Port's historic structures means that a large earthquake on the Hayward Fault or another local fault could devastate the waterfront and dramatically alter the image of the city.

The Finger Piers

Of particular concern are the Port's historic "finger" piers. From Fisherman's Wharf to Mission Bay, these piers extend out from The Embarcadero, supported by wooden or concrete piles. The piers are interspersed with "marginal wharf " facilities that run parallel to The Embarcadero. Many of these structures were built in the period leading up to the construction of the Panama Canal (1910), as San Francisco positioned itself for a major expansion as the West Coast's major port.

The finger piers were originally built to function as cargo terminals for "break-bulk" cargoes (individual products moved on pallets or bundles). The cargo shed and decorative "bulkhead" buildings that line The Embarcadero sit atop the pier platforms and housed the loading, storage and freight movement of cargo in simple, utilitarian fashion. They are now recognized as significant historic architectural resources, among the last examples of a collection of finger piers in the nation. The Beaux Arts bulkhead buildings create the distinct architectural form that makes The Embarcadero a great urban boulevard.

But the finger piers have long ceased to be needed for their original maritime warehouse purposes. The rise of container shipping in the 1960s and San Francisco's tardiness in investing in appropriate technology began to drive shipping toward the modernized and spacious Port of Oakland. San Francisco's remaining non-containerized cargo activity has been consolidated in the Port's Southern Waterfront.

As a result, many of the finger piers fell into disuse. Some of the aprons and the berths alongside the piers continue to provide berthing for non-cargo maritime tenants. But the Port leases many of the piers on an interim basis for short-term non-maritime uses. With the exception of the recently restored Ferry Building, Pier 1, and Piers 1½-3-5, public access to the finger piers is minimal to nonexistent. Restoring and revitalizing the remaining finger piers and opening up their perimeter aprons, sheltered water basins, and historic interiors to the public is one of the great redevelopment opportunities in the city.

The City took a major step toward preserving these historic resources when it succeeded in 2006 in listing the historic piers from Pier 45 in Fishman's Wharf to Pier 48 south of Mission Creek, now the "San Francisco Embarcadero Waterfront Historic District," on the National Register of Historic Places.

Unfortunately, while these piers have become icons for San Francisco, many are in an advanced state of deterioration. The cost of maintaining and restoring these pile-supported structures over water is daunting. Surveys undertaken by the Port show that its historic infrastructure is crumbling: Numerous piers have been yellowtagged (load restricted) or red-tagged (declared unsafe for any use) by Port engineers, effectively limiting their economic use. Within the past year, the Port has seen two piers (or portions thereof) literally fall into the Bay. Since the 1970s, 15 of the original historic piers have been lost - approximately one every two years.

Pier 70 and the Southern Waterfront

The finger piers are not the only major redevelopment opportunity on Port property. The Port owns approximately 65 acres of filled land and former uplands in the vicinity of Pier 70, just east of Potrero Hill and the Dogpatch neighborhood. Pier 70 has been home to San Francisco's ship-building and repair industry for 150 years. The site is still home to the Port's Drydock No. 2, the largest floating drydock on the west coast of the Americas and the longest continually operating drydock operation on the West Coast. The remainder of the site contains Victorian-era industrial buildings, including the awe-inspiring Union Iron Works Machine Shop, which collectively are eligible for listing on the National Register. These buildings are failing.

South of Pier 70, the Port's piers are mostly land masses built on fill created in the 1960s and '70s to accommodate new container cargo terminals. Since then, the Port has followed the volatile global cargo-shipping industry and adapted its cargo facilities at Pier 80 and 90-96 to accommodate non-containerized bulk and break-bulk cargoes, which supply the city with steel and sand and aggregates for concrete production, among other imports. Built before engineers understood the seismic performance of fill, the cargo terminals could slough into the Bay during a major temblor, eliminating deep-water access in the Port's Southern Waterfront.

Natural Risks

In developed shoreline areas, the harsh conditions of a tidal marine environment and the structural interface between land and water often dictate the need for special engineering design and costly construction specifications. In addition, projected changes associated with global warming and new Federal Emergency Management Agency efforts to map coastal flood hazards in San Francisco will force the City to conduct a comprehensive review of how the waterfront and shoreline areas need to be fortified to eliminate flood hazards and protect against rising Bay waters. The California Climate Change Action Team's most recent report indicates that sea level may rise by as much as 39 inches by 2100. Unchecked, rising seas would engulf major portions of the San Francisco Bay shoreline, including Mission Bay. If this increase in sea level comes to pass, it will necessitate a dramatic rethinking and eventual re-engineering of the city's waterfront, to protect adjacent inland areas and replace vital wetlands areas lost to rising seas.

This risk, however compelling in the current debate over global warming, is remote compared to the clear and immediate risk of a major earthquake. While we don't often think of it, the Port needs to function after an earthquake as a harbor, bringing in supplies and aid, and as a way of moving people, debris and construction materials. The Port's harbor facilities may not survive an earthquake to serve city residents, as the Port did in 1906, and the consequences could hamper the city's post-earthquake recovery operations, potentially for years.

The Port's entire jurisdiction is located within a U.S. Geological Survey seismic hazard area, and most of the Port's facilities were built prior to the adoption of seismic building standards. Recent development projects, such as the Ferry Building, Pier 1, Piers 1½-3-5 and AT&T Park, are built to modern standards. Nevertheless, the risk of catastrophic damage along the waterfront during a major earthquake is high. The City can no longer afford to consider the Port as a separate financial entity, the conditions of which bear no consequence for the city at large.

The Port has conducted facility-condition surveys for all of its property. Many of its facilities are load-restricted, limiting their economic use, or are condemned.

The Port's regulatory setting

With the decline of maritime cargo in San Francisco, the non-maritime use and development of Port lands and facilities has become an increasingly important aspect of the Port's role in the city, as well as a key source of Port revenue. But because of the Port's proximity to the Bay, its land use activities are subject to layers of regulatory oversight and control that are generally absent for development in other areas of the city. These state, regional and local restrictions have played an essential role in protecting the Bay from fill and overdevelopment, but they have also given rise to considerable uncertainty as to what land uses are possible on Port lands and to some extent have contributed to their underutilization. Any solution for the waterfront will need to include strategies for harmonizing these sometimes competing regulatory objectives.

The Public Trust and the Burton Act

Most San Franciscans think the City owns the Port and the waterfront. While the City holds title to Port property, the State of California maintains a sovereign interest in the property and can take it back if it finds the City has failed to properly steward these lands.

When California joined the Union in 1850, it acquired title to all previously unconveyed tidelands and submerged lands within the jurisdiction of the new state. These lands were subject to a legal encumbrance rooted in English common law called the "public trust for commerce, navigation and fisheries." As interpreted by California courts, the public trust ensures that the state uses tidebands and submerged lands for purposes that benefit the people of the state. The state is not free to use or dispose of trust lands for purely private purposes that do not further the objectives of the trust. Since 1879, the California Constitution has prohibited the alienation of tidelands and submerged lands within two miles of any incorporated city. Since 1909, the Legislature has prohibited the sale of any tidelands and submerged lands anywhere in the state.2 The state may, however, grant these lands to municipalities subject to the public trust and whatever additional restrictions the state imposes.

Most of the lands within the boundaries of the Port of San Francisco, filled and unfilled, are subject to this public trust. In fact, the state even administered the Port of San Francisco as a state agency from the late 19th century until 1968, when the state Legislature adopted the Burton Act, which granted the state's interest in the lands to the City. The Burton Act grant was subject to the public trust and subject to additional trust restrictions contained in the act. These restrictions have had serious implications for the development of waterfront properties.

Most importantly, the public trust and the Burton Act place substantial limitations on the uses that can be made of Port lands. The traditional triad of public-trust uses - commerce, navigation and fisheries - has been interpreted by the courts over time to include a number of public and private uses beyond those that are strictly maritime-related. Public parks, open space, wildlife habitat and environmental protection are all permissible trust uses. Uses that enhance the public's use and enjoyment of the waterfront - restaurants, hotels, wateroriented recreation, visitor-serving retail shops, public parking that is ancillary to a trust use - are also allowed. Fisherman's Wharf is a good example of these uses. But uses that are neither water-related nor visitor-serving are generally not permitted. The most important of these are residential, non-maritime office and localserving retail uses. The state has also interpreted the trust as limiting certain recreational uses that are viewed as serving primarily local residents.

These public-trust use restrictions have played a critical role in protecting the Bay, reserving the shoreline for uses that require water access, and preventing privatization of the waterfront. But they have also led to the underutilization of a number of Port properties that would otherwise appear to be appropriate for a wider range of development options. Of particular note are the "seawall lots": Port-owned parcels located on the landward side of The Embarcadero and surrounded by private residential and office development. These have been used by the Port primarily as surface parking lots, in large part due to trust use restrictions.

The Burton Act (together with subsequent amendments to the San Francisco Charter) also established the Port Commission as an agency of local government, with exclusive control over the lands granted to the City. There was a conscious effort by the state to establish a single entity - separate from the rest of the City, but operating as a City department - as both the property owner and regulator of Port lands.

The effort was not totally successful. Three other entities now have a major impact on development of Port property: The City itself, through its authority over non maritime development; BCDC, through its permit process regulating development in or over San Francisco Bay and within the first 100 feet of the shoreline; and the State Lands Commission, through its oversight of the state tidelands the Port holds in trust under the Burton Act. The three have often complementary but sometimes contradictory policies for waterfront use - and each has, in effect, a veto over individual waterfront projects. The Port is also subject to requirements imposed from another quarter: the San Francisco electorate.

The Port celebrated the grand opening of Piers 1½-3-5, above right, in 2007. This mixed-use development project has received an award from the California Preservation Foundation. The Port’s Mission Bay shoreline, above left, contains “ghost piles” from piers that have disintegrated into the Bay.

Proposition H and the Waterfront Land Use Plan

In 1990, in reaction to simultaneous proposals for hotel development on three different piers, Proposition H was placed on the ballot and approved by San Francisco voters. Proposition H prohibited hotels on Port piers. More importantly, it required the Port to develop a "Waterfront Land Use Plan" with maximum public participation for all its property bayward of The Embarcadero.

The Port had participated in, but had not led, previous waterfront planning efforts. In 1991, the Port Commission decided that it needed to chart its own course. The commission took the unprecedented approach of establishing a Waterfront Plan Advisory Board charged with recommending a plan for the commission's consideration. To ensure broad representation, advisory board members were appointed by the mayor, members of the Board of Supervisors, and the commission. The mayor appointed the chair of BCDC as chairman of the Waterfront Plan Advisory Board.

Over four years, the advisory board, its committees, consultants and guest experts met twice a month. The scope of work was exhaustive: evaluating the needs of each maritime industry, defining desired uses and qualities to promote along the waterfront, and creating waterfront subareas and "opportunity areas" to define where and how development should take place. The resulting plan was embraced by the Port Commission, which further directed its staff to develop more detailed policies to address urban design, public access and historic preservation, to accompany the advisory board's land-use plan. Following the completion of a program environmental impact report, the Waterfront Plan was approved by the Port Commission in 1997. Notwithstanding this unprecedented effort, the success of any plan relies on an intricate choreography of many regulatory players in a very public arena.

City and County of San Francisco

While the Port Commission has "exclusive jurisdiction" over Port property under the San Francisco City Charter, other agencies and departments of the City influence waterfront development, both formally and informally. Since voters approved a charter amendment in the late 1970s, the Board of Supervisors has had fiscal approval authority over all contracts in excess of $1 million and leases with a term of more than 10 years (and, therefore, virtually all public-private development projects).

The City's land-use regulations (zoning, height, bulk, etc.), as administered by the Board of Supervisors and the Planning Commission, also apply to Port non-maritime land uses. Port projects are further subject to environmental review under the California Environmental Quality Act as administered by the Planning Department, with final CEQA determinations appealable to the Board of Supervisors. In addition, the Board of Supervisors recently adopted an ordinance requiring fiscal-feasibility review of projects costing more than $25 million and requiring public subsidies of $1 million or more. This ordinance requires Port projects involving rent credits3 to obtain an affirmative finding from the Board of Supervisors that the project is fiscally feasible, based on criteria such as direct and indirect financial benefits to the City and available funding for the project, prior to commencing environmental review under CEQA.

Following the Port Commission's approval of the Waterfront Plan, the Port worked with the Planning Department to develop amendments to the City's General Plan, Planning Code and Zoning Map to align the City and Port's land-use and urban-design policies for the waterfront. These amendments were approved by the Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors, and provided the basis for a number of waterfront development projects that have since been approved, including the Ferry Building, Pier 1, Piers 1½-3-5 and Piers 30-32.

Recent history has seen fewer success stories, as several high-profile projects have foundered in the face of strong local opposition. In 2000, city voters adopted an advisory measure urging the Port to pursue a Bay-oriented public educational facility at Pier 45 instead of the interactive, San Francisco-themed museum proposed by Malrite for that location. In mid-2005, the Board of Supervisors lowered the height limits for the site of a hotel proposed by the Port, effectively stopping the project. And in late 2005, the Board of Supervisors found that the mixed-use retail/ recreation project proposed by Mills Corporation was not fiscally feasible, thus preventing the project from proceeding to environmental review.

The experience with these recent development projects - specifically the time and predevelopment costs that the existing City regulatory process can consume - point up the need for a stronger consensus within the City and with its regulatory community regarding such development before the Port solicits private investment in specific development proposals. The principal reason for this is that the Port cannot afford to finance its development projects with high-risk capital.

Pier 70 has been home to ship construction and repair for 150 years, and remains home to

the largest floating drydock on the west coast of the Americas. The Union Iron Works

Machine Shop at Pier 70 is an example of Victorian-era industrial architecture that is eligible

for listing on the National Register and is an ideal candidate for adaptive reuse.

San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission

BCDC was created, with SPUR's guidance, as a temporary state agency in 1965 and became permanent in 1969. The deputy director of SPUR became its first executive director. Under the McAteer-Petris Act, BCDC is charged with regulating all filling, dredging and substantial changes in use within its jurisdiction. BCDC's permitting jurisdiction includes all areas of the Bay that are subject to tidal action up to the mean high tide line, and a "shoreline band" extending inland 100 feet from the mean high tide line. The term "fill" includes replacement and significant repair of pile-supported structures. Use of fill must also be consistent with the public trust and can be permitted only for "water oriented uses."

For many years, BCDC allowed fill on publicly owned land only for replacement of pile-supported structures for "bay-oriented commercial recreation and public assembly," and generally permitted only half the area of the former pile-supported structure to be replaced. This policy, known as the "50 percent fill rule," effectively prevented the historic preservation of San Francisco's finger piers. Operating under these criteria during the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s, BCDC approved replacement fill for Pier 39 over water, but not much else.

Once the Waterfront Plan was completed, BCDC amended the rules contained in its Special Area Plan for the San Francisco Waterfront to make it consistent with the Waterfront Plan. The amendment replaced the 50 percent fill rule4 with new pier-specific requirements for public access and open space under the new BCDC Special Area Plan. BCDC can now approve any project that is consistent with the public trust, the terms of the Burton Act, the San Francisco Waterfront Special Area Plan and the Waterfront Land Use Plan.

The Waterfront Plan and the BCDC Special Area Plan both attempted to bring more certainty to the development-approval process. But these plans assumed that all projects subsequently approved would be consistent with the public trust - a factor that would give rise to its own set of uncertainties.

The California State Lands Commission

The State Lands Commission oversees the administration of the state's granted lands, including the Port lands granted to the City by the Burton Act. BCDC looks to the commission for guidance on trust-consistency determinations. Further, the State Lands Commission can sue (and has sued) its grantees when it believes trust principles are being violated.

For many years, the State Lands Commission played a relatively minor role in project review along the San Francisco Waterfront. The State Land Commission's participation in waterfront project approval significantly increased as major, nontraditional and mixed-use projects were proposed in the 1990s. Project lenders wanted certainty that a project lease approved by the City would be honored by the State in the unlikely event that the State exercised its sovereign right to revoke the Burton Act grant and retake title to Port property. Thus, projects such as AT&T Park, Pier 1, the Ferry Building, the Pier 30-32 Cruise Terminal, and Piers 1½-3-5 drew the State Lands Commission and the state Attorney General's Office ever more deeply into complex trust questions surrounding specific projects along the San Francisco waterfront.

The State Lands Commission and the Attorney General's Office worked closely with project proponents, the City, BCDC, the Port and the public to arrive at solutions that would respect the values and objectives that the public trust was designed to protect and advance. In particular, the commission has determined that in the context of a broader project that promotes the public trust, historic preservation is an exercise of the trust. In this way, the State Lands Commission afforded San Francisco much greater flexibility to incorporate non-trust uses such as general office or non-trust retail into its historic preservation projects than is allowed in new construction on trust property.

Nevertheless, clear guidelines as to the trust consistency of certain uses, and as to the proper balance between trust and non-trust uses allowed in historic preservation projects remain absent. This has made closure on trust issues complicated and time-consuming for specific projects. A determination of trust consistency often cannot be made until a project's uses and design have been established at a high level of detail, which usually occurs late in the entitlement process, after considerable predevelopment costs have been incurred. The resulting costs and lack of predictability are a major disincentive to investment. Further, the State Lands Commission and the Attorney General's Office, mainly in response to proposals from Southern California but pressed in part by some proposals along the San Francisco waterfront, have taken a careful and cautious approach to public trust consistency. For example, under the State's present interpretation of the law, the public-trust consistency of a project is determined on a structure-by-structure basis, rather than on a project-by-project or on a limited geographical basis - even though there is some precedent in other states for a different approach. Project-specific state legislation is often required to resolve uncertainties as to permitted uses.

But the State Lands Commission and the Attorney General's Office cannot be expected to be more flexible on matters of trust consistency when trust-consistent developments - such as the recreation, commercial and open-space project proposed by the Mills Development Corporation at Piers 27-31, or the hotel project proposed at Broadway and Embarcadero - are approved by the Port, the commission and the Attorney General's Office, only to be rejected by the Board of Supervisors in response to local opposition. The City's pleas for greater flexibility in the interpretations from the State Lands Commission and the Attorney General's Office must also ring somewhat hollow when the City itself refuses to permit hotels - a clearly trust consistent, revenue producing use - on Port land bayward of The Embarcadero.

Fixing the land-use approval process for Port development will require movement on the part of all parties with a stake in the outcome: the City, the state and the local electorate. The landuse approval process must be streamlined, and more flexibility on permitted uses is needed from all sides. But this can only be accomplished if all concerned are assured that their objectives will be addressed and major conflicts will be resolved early in the process.

A broken financial model

From its inception in 1969, the Port of San Francisco has been an enterprise department of the City5 - that is, its operating and capital budgets are derived wholly from the revenue generated from its properties. Other than occasional special purpose grants from state agencies, it receives no resources from the State of California or the City's General Fund. Currently, the Port's revenues are nearly $60 million annually, virtually all in the form of lease revenue from its properties.

In addition, when the City and County of San Francisco took on the management of the Port of San Francisco, it inherited a debt of more than $50 million from the State. Ironically, this debt - and a desire to fund maritime cargo improvements in the Southern Waterfront - led the City to propose dramatic and inappropriate waterfront development that led to local downzoning of the waterfront and a further decrease in the value of Port assets.

Thus, from the outset, the Port has been able to invest very little in its infrastructure. The Port's negligible bonding capacity constrained its ability to address long-term capital needs, even though the Port has long known that its assets were failing. However, the Port, the City and the state did not have a full understanding of the magnitude of the Port's infrastructure problem until the Port produced its first 10-year Capital Plan in 2006.

The Port's 10-year Capital Plan is based on a comprehensive survey of the physical condition of all Port properties under its ownership. The Plan identifies the cost of bringing the Port into basic compliance with health, safety, seismic and Americans with Disabilities Act regulations, as well as fulfilling waterfront open-space needs, at nearly $1.5 billion. Almost one-third of the costs identified in this Capital Plan are for substructure repair and seismic strengthening of the Port's pile-supported structures. The Capital Plan is a basic fix-it plan, not the sweeping vision of the Waterfront Plan. If all of the Capital Plan improvements are made, the Port will still look much the same as today, with the exception of some new open spaces.

Yet, almost $1 billion of the Capital Plan is unfunded. The actual and potential funding sources identified in the Plan - tenant repairs, budget allocations and development projects, as well as Port-sponsored revenue and taxincrement bonds - are not nearly enough to implement the plan. While the Port spends a greater percentage of its annual operating budget on capital projects than most City departments, that figure is only $7.5 million annually. At this rate, it would take more than 200 years to implement the Port's Capital Plan. Nor can the Port rely on bonds repaid with Port revenues to finance Capital Plan improvements: if the Port were to secure a bond issue of $1.5 billion, it would require annual payments totaling approximately $118 million over 30 years. This far exceeds the Port's current revenue-generating capacity and bonding ability. In short, hard choices need to be made regarding allocation of limited resources.

When the Waterfront Plan was adopted in 1997, it was understood that commercial development within the opportunity areas identified in the Waterfront Plan would not generate sufficient revenue to absorb the cost of upgrades to those piers remaining in maritime use as well as fund open-space improvements required by BCDC. There was, however, an understanding that redevelopment of Port property would increase revenue to the Port's Harbor Fund. The Waterfront Plan Advisory Board and the Port Commission explored alternative funding sources, such as general tax support, and the Advisory Board recommended that such sources be pursued. However, their task was to develop a landuse plan, and they recognized that the plan implementation was necessarily a work in progress. As projects came on line, however, the Port quickly realized that the financial challenges were more severe than anticipated.

The Embarcadero Waterfront Historic District, with the Ferry Building as its centerpiece, top, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2007, enabling the Port to obtain federal historic-preservation tax credits for its adaptive reuse projects. The 40-acre Pier 90-94 backlands in the Southern Waterfront, above, is one of the few remaining undeveloped industrial sites zoned M-2 in the city. Development of this site should relate to the Port’s Pier 90-96 maritime terminals that are immediately adjacent to the site.

The Ferry Building, Pier 1 and Piers 1½- 3-5 all sit at the foot of Market Street in the most transit-accessible location in the city. Each of these structures was individually eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, thus providing developers with access to the Federal Historic Tax Credit program. Nevertheless, the far-greater-thanexpected costs of seismic and substructure upgrades, combined with the enormous cost of preservation of these structures consistent with the standards of the secretary of the Interior Department, resulted in great public architecture and public spaces - but not in significantly increased revenue to the Port.

As the costs of substructure repairs, seismic upgrades and historic preservation rose, the associated return on investment dropped. By the time the Piers 1½-3-5 Project was approved for development in 2002, it was clear that Port development projects were barely covering their own development costs within the first 10 years after project opening, and could not be relied upon to generate substantial new revenues to support the Port's core maritime functions and develop costly new waterfront open space.

In 2006, San Francisco Piers LLC, a subsidiary of Bovis Lend Lease, allowed its exclusive rights to construct a cruise terminal and associated retail and entertainment venue on Piers 30-32 to expire, even though the project had obtained most of its regulatory approvals. The developer cited the increasing cost of retrofitting and seismically upgrading the rotting pilings of Piers 30-32 as the major factor in its decision.

Further, the cost of construction is rising at rates of up to 10 percent annually. It is generally safe to say that the Port's historic piers have negative residual land value. To put it another way, it costs more - often approaching $200 per square foot - to seismically upgrade the Port's finger piers and repair the associated substructure than it does to purchase comparable private land in the city. This bleak financial outlook calls into question the premise of the Port as an "enterprise department" capable of supporting itself through its own revenues.

The only factor offsetting this dismal picture is that there is no land in the city that is comparable to the piers and their dramatic location over water. The piers establish an important transition between the city's urban edge and the expanse of San Francisco Bay. These unique qualities provide the incentive for the kind of public and private investment in the waterfront that will be necessary to overcome the formidable constraints on waterfront redevelopment.

But private development alone will never be enough to generate the revenues needed to save the finger piers and achieve the public benefits envisioned in the Waterfront Land Use Plan. Substantial public subsidy is needed. Indeed, without it, the Port is unlikely to be able to leverage the benefits of private capital in the first place. If Port-wide revitalization is to occur, a greater share of the tax revenues generated by the Port must be directed back to the Port.

Access, parking and transit: The Embarcadero Roadway

Recent waterfront development projects have been challenged not only by the regulatory and financial constraints discussed above. The public has little confidence in the ability of the City's transit system to provide needed access, yet also fears auto congestion and parking problems arising from development.

This lack of consensus would appear to be counterintuitive, since in 2000 a 20-year City effort to convert the industrial road and railway that once defined The Embarcadero culminated in today's public promenade and public-transit corridor. Nevertheless, while The Embarcadero has been embraced by residents, the City has been unable to fully exploit this transportation facility. Notably, the level of transit service along the center dedicated light-rail line falls far short of its potential capacity. People love riding the F-Market historic streetcars between the Agriculture Building and Fisherman's Wharf, but the currently low carrying capacity falls short of what is needed.

The Embarcadero is designated in the San Francisco General Plan as an important street for all modes: It is a major arterial street, a major transit corridor and a priority bicycle and pedestrian route. Existing and new highdensity development at the foot of Telegraph Hill and in Rincon Hill, Mission Bay and South Beach is predicated on increased waterfront transportation capacity. Maximum public access to the waterfront is also based on a transit-first policy.

Improving transit capacity along The Embarcadero will be a challenge. As discussed in previous SPUR reports, there is a major structural defect in the way San Francisco funds and supports public transit. Current assessments indicate that the Municipal Transportation Agency requires an additional $100 million annually in operating funds to provide the drivers, supervision and maintenance capacity to support current levels of transit service in the City. With its Transit Effectiveness Project, the MTA is studying how existing resources can be managed better to yield increased service.

Where transit does not work, people drive cars and need to park them. Port, BCDC and City plans all promote locating new parking structures inland, away from the piers, to protect pedestrians strolling down Herb Caen Way and bicyclists in bike lanes. Port efforts to carry out this policy have met with strong resistance by transit advocates who oppose construction of large parking facilities. The Port has attempted two different proposals to develop parking structures on inland property, both of which failed.

The failure to solve these transit and parking questions continues to plague consideration of new development. Nowhere has this problem been more evident than along The Embarcadero, where Herb Caen Way and waterside developments have attracted so many new visitors and residents to enjoy the Bay.

Project-by-project battlefields are not an effective forum for real solutions, and waterfront redevelopment cannot solve the transit deficit along The Embarcadero. Ultimately, the City, the Port and the MTA must find a way to develop and fund an approach to integrated land use and transportation planning. But the Port cannot afford to wait that long for transportation relief. Shorter-term solutions are needed. The Embarcadero provides an ideal laboratory for testing transportation ideas that could benefit both the Port and, if successful, the city at large.

A way forward

There are stark truths about San Francisco's waterfront that government, private developers and the public must confront.

First, it is essential that the process for waterfront development be streamlined and made more certain. The multiple layers of approval from public entities with distinct and sometimes overlapping mandates, together with uncertainty as to permissible uses, have substantially increased the risk for private capital. Lengthy processes for project approval eat up huge amounts of pre-development costs that would be better spent on public improvements. Developers respond to rising pre-development costs by proposing more private uses, which in turn provokes greater stakeholder opposition. Developers also pass on the increased risk premium to the Port, further decreasing the Port's limited return.

What is needed is increased public planning. An integrated planning process that brings together state, regional and local agencies can provide a road map for identifying the right mix of public and private uses within defined areas of the waterfront that will bring greater certainty, attract private capital, and ensure that public benefits and uses are established. Second, attaining public-oriented redevelopment of the waterfront will require significant public investment. The Port's capital needs are too great and cannot be met through project-generated revenue alone. Both the City and the state must provide funding to help accomplish the public program they envision for the waterfront.

Third, developers must understand that development of the waterfront is not an opportunity for maximizing returns on investment, even with public subsidy. Waterfront projects must be, first and foremost, public in orientation. Developing along the water's edge must be understood by developers as an invitation to create great architecture for the city and great public spaces on the waterfront.

And finally, not everything can be saved. Even under the best-case scenario, the combination of public and private resources will not be enough to preserve every historic pier and structure on the waterfront. There simply isn't enough money available to fund a $1.5 billion 10-year Capital Plan. These recommendations can only reduce the hard choices that must be made, not eliminate them.

The Waterfront Land Use Plan: A Subarea Planning Approach

Proposition H, approved by voters in 1990, required both the adoption of the Waterfront Land Use Plan and a periodic review of the plan every five years after its adoption. The plan defines policies and locations for the Port's diverse portfolio of maritime industries. This issue was a primary concern to San Francisco voters when they approved Proposition H. Consequently, the 27-member Waterfront Plan Advisory Board gave priority consideration to meet maritime business needs.

Heavy industrial, land-intensive maritime uses (ship repair and cargo shipping) are located primarily in the Southern Waterfront. Other commercial maritime uses, such as cruise vessels, harbor support, fishing, ferries, excursion boats and marinas, are located primarily north of China Basin. Almost all maritime industries require some form of Port or public financial support, because lease revenues from these uses are insufficient to fund capital improvements and maintenance.

To help address this shortfall, as well as to create authentic new development to reconnect the city with the waterfront, the Waterfront Plan identifies 13 development opportunity sites and several transitional maritime areas in the five subareas of the waterfront. In these locations the plan seeks to preserve or restore maritime operations and berth facilities, finance preservation of the Port's historic resources, and create development activities and public open space that attract the public to experience and enjoy the Bay.

Some of the Port's recent development failures demonstrate market and financial challenges, while others reflect changes in the public's understanding and expectation of waterfront development projects. Over the past five years, the Port and waterfront constituents have improved their understanding of what it takes to successfully implement projects, as well as the unique physical and economic challenges facing the Port. Those lessons learned should inform any review and update of the Waterfront Plan, in order to reduce or avoid the types of controversies that have hampered some of the Port's projects.

SPUR recommends that the Port update the Waterfront Plan to incorporate lessons learned, reflect current forecasts for maritime uses on the Port's property and develop more specific transportation policies. An update of the Waterfront Plan could also incorporate performance measures or benchmarks that could allow the Port to measure its progress in specific areas that are relevant to the entire waterfront, such as maintaining and expanding the Port's maritime portfolio, improving public access to the water, historic preservation, and wildlife habitat restoration. This update should be overseen by the Port Commission with a robust program for public involvement.

SPUR also recommends a new planning approach that focuses on individual subareas and involves the State Lands Commission and BCDC at the planning stage. This approach would have several advantages that could help overcome some of the obstacles facing projects today.

First, a subarea planning effort would provide a way to refine the Waterfront Plan in stages without having to revise the entire plan all at once - a daunting task by any measure. The Port simply does not have the staffing resources to conduct reviews for each area of the waterfront simultaneously. Subareas provide a coherent and manageable planning unit. A public process focused on a subarea is also likely to draw the greatest amount of stakeholder participation, which will help resolve important local and citywide issues early in the process.

Second, subarea planning can be done at a greater level of specificity and resolve some issues that would otherwise arise at the projectapproval stage. This provides an opportunity to streamline the local review process. Under this model, the Board of Supervisors would set policy at the level of zoning and general plan approvals for subarea plans. The Board of Supervisors would also maintain fiscal-feasibility review for projects involving public subsidy. However, city voters could consider replacing the Board of Supervisors' fiscal review of leases for Port development projects that are consistent with adopted subarea plans with fiscal review of such leases by the Controller's Office. This might result in better financial oversight and add further certainty to the development-approval process. Environmental review could also be streamlined through the use of program environmental-impact reports for subareas, which would facilitate project-level CEQA review. However, the planning process should not delay projects already under discussion or in the pipeline.

Third, and most importantly, a subarea planning process provides an opportunity for a new approach to public trust review by the state. A subarea is a discrete planning unit that is ideal for addressing public trust considerations more comprehensively. Involvement of the State Lands Commission and BCDC at this early stage would help provide certainty on the key issue of trust consistency. It would allow the commission to simplify its review of individual projects by shifting from structure-by-structure trust consistency to plan trust consistency. In addition, by increasing certainty in the public uses and benefits to be provided in each subarea, the subarea plan would provide a basis for increased flexibility on the mix of trust and non-trust uses within the subarea. Using this approach, the state could determine whether the development program for each subarea, taken as a whole, is consistent with the public trust.

Building on the Waterfront Plan process, the City, BCDC, and the State Lands Commission should cooperate, possibly through a jointpowers agreement, to create a structure and process for the creation of subarea planning committees that include appointed citizen representatives. To build support for an updated Waterfront Plan, the agencies should work closely with waterfront stakeholders to develop a planning process that is inclusive and, at the same time, holds everyone accountable to the schedule and program that is agreed on. The subarea committees should conduct staffed workshops to present and discuss the most critical issues that should inform subarea plans. The subarea committees should oversee a public planning process to develop a shared vision, resolve conflicting public priorities (to the extent feasible), and develop specific development goals and objectives. During this process, the subarea committees should generate land-use scenarios for each subarea to test what combination of revenue-producing uses (office, retail, hotels and housing) will meet Waterfront Plan objectives (maritime, historic preservation, open space/recreation, seismic retrofit, environmental) in a financially viable manner. The subarea committees should seek public comment on scenarios for a subarea to create a process that balances competing objectives.

The Pier 90-94 backlands area is home to the city’s construction materials industries, including two of the city’s three concrete-batching plants.

What should a Waterfront Plan update and subarea planning involve? The review should focus on addressing the Port's capital and economic crisis, and should balance the different revenue- generating capacities of each area of the waterfront with the different capital needs described in the Port's 10-year Capital Plan. SPUR recommends answering the following major questions during these planning efforts:

Maritime: Which pier sheds, aprons and berths need to be preserved for maritime use? How can the City best preserve the M-2 zoning and the maritime industrial terminals at Pier 80 and Piers 90-96? How can the Port expand its inland-waterway portfolio (ferries, harbor services, etc.)? Which piers and open land are not required for the Port's current and projected maritime needs?

Historic preservation: If certain historic piers in the proposed Embarcadero Historic District are too expensive to redevelop or the mix of uses required to make redevelopment feasible is not acceptable to the community, what should happen to these facilities? If some piers are removed, how would this affect the integrity of the Embarcadero Historic District?

Open space and recreation: What is our vision of major open spaces along the water? How can we accommodate the Blue Greenway in the Port's industrial Southern Waterfront? How do we secure adequate funding resources for implementation?

Wildlife habitat, biodiversity and connection to the Bay: What opportunities exist for habitat restoration and education about natural areas? How do we build upon the Port's record of wetlands enhancement at Heron's Head Park and Pier 94? How should the Port coordinate with San Francisco Recreation and Park Department and the California Department of Parks and Recreation to maximize habitat and wildlife-watching opportunities at locations such as India Basin and Yosemite Slough?

Other public trust uses: How do visitor-serving uses such as hotels and hostels fit into the Port's public-trust mandate? Where should such uses be authorized?

Financial: How do the projected capital costs and revenues from a given subarea fit into the Port's overall financial plan? What mix of uses and how much of each major use type, including revenue-generating non-trust uses, is required to preserve historic resources in the subarea and to support the Port's maritime and open-space maintenance requirements? Which development opportunities are likely to yield the most significant early infusion of funds to address the Port's capital needs? Starting with the funding needs outlined in the Port's 10-year Capital Plan, what level of public investment is required?

Transportation: What is the best combination of public transit, bike, pedestrian and parking resources that will serve new development, and how will it be financed? How can new development best add to transit capacity along Muni's F and E lines? How can improved transit reduce the need for additional parking? If new parking is required, where should it be located and how should it be designed? How can the Port effectively expand waterside transportation such as ferry service and water taxis?

Economic access: How do we ensure that development efforts serve and are affordable to residents and visitors of all incomes?

Environmental sustainability: How can Port development meet or exceed the City's sustainability policies? How can we ensure that low-impact development technologies (such as the vegetated swales at the Pier 90-94 backlands) will be incorporated into the Port's entire water management system? Can an "eco-industrial park" concept, combining industrial recycling enterprises that make use of each other's products and byproducts, work for the Port's Pier 90-94 backlands?

Public orientation: What makes a waterfront project successful? How can future waterfront development projects become destinations for both residents and visitors?

Subarea planning efforts may yield recommendations for:

> changes to the Waterfront Land Use Plan

> modifications to the BCDC Special Area Plan and/or the Seaport Plan

> other land use changes, such as amendments to zoning controls, if required

> priorities for development-opportunity sites and required staffing and resources

> changes to transit, bicycle, pedestrian or parking policies or designs

> possible changes in the orientation and levy of public-benefit exactions for Port projects

> state legislation to permit the State Lands Commission and BCDC to address public-trust consistency issues on a subarea basis rather than structure by structure

The subarea committees should produce final recommendations for the Port Commission, BCDC and the California State Lands Commission regarding their proposals. After subarea plan adoption by each agency, the State Lands Commission should be able to review individual Port development projects within a subarea for consistency with the subarea plan previously reviewed and approved for trust consistency.

SPUR cautions that while a planning process is necessary to resolve conflicting visions for our waterfront, the San Francisco waterfront is a citywide and statewide asset. Therefore, it is essential that the planning process include voices representing these broader interests.The Port should investigate varied approaches to enhancing public participation in planning exercises beyond the planning workshop format, including but not limited to weeknight and weekend forums co-sponsored with neighborhood or public-policy groups, and active outreach to citywide interest groups.

Expand allowable uses on Portlands

For subarea planning to be effective, a broader mix of uses on Port property must be made available. In their current form, state and local use restrictions, though designed to protect important policy objectives, can be fairly blunt instruments and at times work at cross-purposes.

The seawall lots, for example, are subject to public-trust use limitations even though they are on the landward side of The Embarcadero and are generally not needed for trust purposes. Their use for surface parking degrades what should be a powerful urban form along the city's edge, and substantially limits the Port's ability to raise revenues for important trust projects such as preserving the finger piers.

This graphic shows a possible breakdown of public versus private investment if SPUR’s recommendations are

This graphic shows a possible breakdown of public versus private investment if SPUR’s recommendations are

implemented, as applied to a cross-section of major Port development opportunities that are likely to become viable

with public investment. It shows that the recommended public subsidies would leverage private equity to redevelop

the waterfront. Under this scenario, the ratio of private to public investment would be approximately 5-to-1.

The piers themselves are afforded a greater level of use flexibility within the historic sheds and bulkhead buildings under the State Land Commission's current interpretation of the trust, but not enough to attract the private investment needed to undertake costly structural improvements. Recent pier development projects such as Pier 1 and Piers 1½-3-5 have relied heavily on a use usually not permitted on trust lands - general office - as a primary revenue generator to pay for historic preservation and public-access improvements. At the same time, hotels - one of the few trust-consistent uses capable of generating substantial revenue in San Francisco - were prohibited on piers by the local electorate under Proposition H. As enacted, the hotel ban applies even where the use is entirely contained within a historic pier building.

SPUR believes that current use restrictions can be modified to allow for greater flexibility to reduce conflict and to produce more successful subarea plans, without undermining the public orientation of the waterfront:

> Remove seawall lots and other surplus land from the trust. The City and the state should jointly pursue legislation that would lift trust use restrictions from those seawall lots that are surplus to the trust. The Port has estimated that development of nine vacant seawall lots free of the trust could yield up to $12 million in new revenues annually. In particular, Seawall Lot 337 in Mission Bay is the most promising revenue opportunity and should be prioritized for development first. The proceeds from development of these sites could be earmarked for historic preservation and other trust-consistent projects for which funds are desperately needed, and can be used to leverage new debt for public purposes. The Port also owns a number of surplus "paper street" fragments that are not used or not needed as rights-of-way, several of which have been built upon. Legislation should be sought allowing the Port to dispose of these paper streets and use the revenue to implement its Capital Plan.

> Amend Proposition H to allow hotels bayward of Embarcadero under certain limited circumstances. The City should place a measure on the ballot to modify the hotel ban under Proposition H. Exceptions to the ban should be limited to a few hotels consistent with the existing historic district. Approval of any hotel must be contingent on (a) the completion of a subarea planning process like the one recommended earlier in this paper; and (b) a design that takes advantage of its Bayfront setting and meets the highest aesthetic standards.

> Allow for broader mix of non-trust uses within historic structures. The Port should have wider latitude to lease portions of the historic piers and other historic buildings to help finance preservation. Criteria can be developed through the subarea planning process to ensure that public-trust purposes are not compromised. For example: placing public trust uses in the bulkhead buildings and the front of pier sheds; concentrating non-trust uses away from The Embarcadero or on the second floor of proposed projects; providing public access around the shed and within the bulkhead buildings; and ensuring public views of historic features of shed interiors. Subject to these criteria, and in the context of an adopted subarea plan that has been reviewed and approved by the State Lands Commission, the Port should be able to devote a greater portion of historic buildings to non-trust uses.

Taxes Generated at the Port Should Be In vested in the Port

The Port's real problem is the lack of financial resources necessary to address waterfront blight. Cities commonly combat blight with a combination of tax incentives and reinvestment of new taxes generated in blighted areas. San Francisco needs to employ these and related tools to rejuvenate and preserve its historic waterfront.

In 2005, the California Legislature passed a measure enabling the Port of San Francisco to establish an Infrastructure Financing District to capture the local City and County of San Francisco share of increases in property tax (possessory-interest tax) collections from Port property, subject to Board of Supervisors approval. IFDs function much like redevelopment project areas, and do not involve tax increases.

In contrast to redevelopment law, the IFD legislation does not require the public agency to make a finding that a subject area is blighted (although such blight clearly exists along the waterfront) or require a set-aside of a portion of the tax increment for affordable housing (except when the projects to be financed through the IFD displace housing). Further, adoption of an IFD does not affect the land-use requirements or zoning designations for the area.

SPUR recommends the following measures, some of which are currently being pursued by the Port staff, to facilitate the elimination of waterfront blight and to preserve those historic resources that can be saved.

Build high-quality Waterfront Parks

The Port is public property that belongs to all Californians. Therefore, SPUR strongly supports development of high quality parks along the water's edge. Dramatic waterfront parks can leave an indelible impression on visitors and add to the quality of life in the city in a way that is impossible to measure in financial or economic terms. The success of the Hudson River Parkway in New York, Millenium Park in Chicago and Crissy Field locally are excellent examples of the striking potential of waterfront recreation.

As the City pursues voter approval of new general-obligation bonds and applies for Proposition 84 and Proposition 1C funds, it should prioritize funding for high quality parks on Port property. Realizing the type of vision currently being pursued for the Hudson River Park Greenway, due to its enormous expense, would require the type of private fundraising that Chicago accomplished with Millenium Park. John Bryan, the former president and Chief Executive Officer of Sara Lee Corp., led a private fundraising effort that raised $205 million of the total $475 million capital costs to build Millenium Park, including 85 gifts of $1 million or more.

One way to attract more funding for waterfront parks may be through partnership with park agencies. San Franciscans enjoy an amazing legacy in the successful effort led by SPUR and Sierra Club members - now almost 40 years ago - to establish the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, which preserved the lands surrounding the Golden Gate. While the GGNRA incorporates major coastal and Bayfront areas in San Francisco, its reach does not extend to San Francisco's Eastern Waterfront.

The Port and the City should investigate a high-level partnership with the GGNRA or the California State Parks Department to provide future stewardship for natural areas such as Warm Water Cove and Heron's Head Park, and perhaps also for areas that should be preserved as unique maritime historic assets.

Waterfront and Bay Recreation

With the construction of Herb Caen Way along the waterfront, San Francisco enjoys a new, urban facility for biking, running and strolling along the Bay. Herb Caen Way is an urban park for the 21st century and is extremely popular with residents and visitors alike.

The Port and the City should develop a continuous path connecting the Northern Waterfront from Crissy Field to Hunters Point, including a Blue Greenway through, or at least with views of, the Port's industrial lands in the Southern Waterfront. Continuous pathways are a significant public value for purposes of recreation and open-space planning, as we have seen in efforts to establish the San Francisco Bay Trail. In planning for this effort, the Port and the City should revisit the design of The Embarcadero Roadway to create Class 1 bike paths physically separated from cars. One retrofit option that may be relatively affordable would be to build bike paths between the sidewalks and the parked cars along the entire length of the roadway.

Residents of the city's eastern neighborhoods need more opportunities to swim and enjoy recreational boating. For more than a century, the city has been cut off from its northern and eastern waterfronts by major industrial operations along the water, including the former rail yards in Mission Bay. The city's Sunset, Richmond, Presidio, Marina and North Beach neighborhoods all have a close, physical connection to their respective waterfronts. South of AT&T Park, residents and visitors enjoy very limited opportunities to enter the water for recreational boating purposes and even fewer opportunities to swim in the Bay. As the Port plans recreational access in the Southern Waterfront, it should place a premium on opportunities for residents to enjoy swimming, sailing and hand-powered boating along this stretch of the Bay.

Sadly, the city's Eastern Waterfront is seriously contaminated by historic industrial activities. Attaining the water quality necessary to allow safe water contact cannot be accomplished by the Port alone, and will require the cooperation of the federal government, the Regional Water Quality Control Board or the California Department of Toxic Substances Control and the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission.

There are a number of potential funding sources for preserving historic piers along the waterfront. The estimates

are based on financial modeling performed by the Port assuming likely development scenarios for each case. As

shown in the table, the major financing strategies recommended in this paper would be sufficient to make specific

development opportunities on Port property viable. In some cases, the proposed public subsidies do not provide a

solution for extraordinary substructure and/ or seismic strengthening costs.

Wildlife Habitat and the Enjoyment of Nature

San Francisco is fortunate that part of its shoreline remains free of a seawall - where land and water are allowed to meet, and the tide can go in and out as well as up and down. In these areas, where the elevations are right, there exist remnants of the extensive tidal marsh system that provided a rich bounty of seafood and waterfowl for this area's first inhabitants and many who came afterward. Although the wetlands at Mission Creek, Islais Creek, Pier 94, Heron's Head Park, India Basin and Yosemite Slough are located considerably bayward of the natural shoreline and are tiny slivers compared with the marsh acreage of the 1700s, these Port holdings and shared holdings offer the same biological diversity and values as the indigenous Bay-edge ecosystem.

Preserving, restoring and interpreting this natural heritage and associated human uses such as the Ohlone shell middens and Chinese fishing camps are as important to many people as preserving the historic resources of the northern waterfront. The Port has done an admirable job of working with community groups on the enhancement of the wetlands of Piers 94 and 98, and in its cooperation with Literacy for Environmental Justice on the soon-to-be-built LEED6 Platinum Living Classroom at Heron's Head Park.

Tidal marshes serve as the nurseries that support much of the aquatic food web, including the fish that provide recreational angling or a source of protein for many. They also serve as habitat for a huge diversity of bird life (avocets, egrets, great blue herons, pelicans, and many more) that has been drawing wildlife watchers to the Southern Waterfront shoreline for many years. The Port's wetlands are also the site of many ecological-stewardship work parties, another form of recreation. The Port and the City should pursue opportunities to expand shoreline natural resources and the recreational and educational uses that depend on them, including the removal of the Hunters Point power plant.

As the Port develops new open spaces, it should utilize resources such as BCDC's 2007 publication "Shoreline Plants: A Landscape Guide for the San Francisco Bay" as guides for natural landscaping appropriate to the Bay setting.

The Embarcadero Roadway and Transportation Solutions

Individual Port development projects cannot solve the transportation shortfalls along The Embarcadero, so until the City addresses congestion and transit along The Embarcadero, the Port is unlikely to be able to develop active, publicly oriented uses along the water that draw new visitors.

The Port and the Municipal Transportation Agency are cooperating to analyze the constraints of The Embarcadero Roadway and to design new parking management systems - including new parking meter technology. As this effort continues, SPUR urges City decisionmakers, and in particular MTA and the Port, to view The Embarcadero as a transit corridor on which the City can test funding and operational solutions for possible implementation citywide. Possible ideas to test along The Embarcadero include:

> use of modern low-floor, high-volume streetcars as companions to historic street cars on the F-Line and on the E-Line, as a means of increasing transit capacity along The Embarcadero

> a Class 1 bicycle path separated from traffic, like the Hudson River Greenway in Manhattan.

> a waterfront transportation assessment district to fund higher levels of Muni service and the purchase of new low-floor vehicles along the waterfront. (The City, State and federal governments spent a combined $560 million on The Embarcadero Roadway transportation corridor, enhancing property values along this corridor dramatically. It is time to recapture some of that investment.)

> implementation of the policy - defined in the BCDC Special Area Plan - of moving parking from the piers to land, as the Port considers development of its seawall lots on the landside of The Embarcadero

Herb Caen Way should be a pedestrian resource with as few vehicles crossing as possible. This may entail the construction of structured parking in some locations. If this is necessary, the Port should pursue structures that are below grade, wrapped with other uses, or otherwise designed to present the best architectural face possible to the street and surrounding structures.

Development Priorities

SPUR offers the following policy considerations to guide the Port and the City as the Port pursues future waterfront development. First and foremost, it is critical that the Port pursue near-term development strategies to increase annual revenues and thus its revenue bonding capacity. This means focusing on relatively easy opportunities, such as completing the Seawall Lot 337 planning process (Lot A in Mission Bay) or leasing or developing the Southern Waterfront backlands. As it pursues these development opportunities, the Port should establish a goal of achieving the highest environmental-performance standards for development that Port projects can afford.

Pier 48 to Pier 70: The Port should prioritize planning and development for the area from Pier 48 to Pier 70 above all other development opportunities. Pier 48 and Seawall Lot 337 in Mission Bay represent substantial potential leasing value to the Port, and the area around these sites is developing rapidly. Seawall Lot 337 is 14 acres and represents perhaps the single most valuable piece of property in the Port's real estate portfolio. The Port is poised to capture the upside of land values in Mission Bay if it moves expeditiously to develop appropriate uses in this area.

Continuing further south, Pier 70 is an industrial brownfield site with multiple hurdles to productive reuse. However, it is the site of what is likely the most historically significant collection of Victorian-era industrial buildings west of the Mississippi. There is no other way to describe it: Pier 70 is a gem and has the potential to become one of the city's most distinctive neighborhoods.

Historically, the Port and the City have focused their collective attention on the Northeast, Waterfront and, more recently, the Central, Waterfront. Meanwhile, residents of the southeast neighborhoods remain isolated from the Bay by blighted industrial lands. The Port, which is in the midst of master planning for Pier 70, should continue its commitment to the southeast neighborhoods by prioritizing Pier 70 redevelopment before engaging new development opportunities in the Northern Waterfront (with the exception of those projects, such as The Exploratorium proposed for Piers 15-17, where the Port has a current development partner).

Piers 90-94 backlands: The Piers 90-94 Maritime Terminal enjoys a 44-acre "backlands," or upland area, the site of a former city landfill. While land uses on this property are constrained by its proximity to active maritime uses and geotechnical considerations, property zoned M-2 for industrial use in San Francisco is scarce, and this site represents a significant additional revenue opportunity for the Port.