↓ scroll to explore this exhibition ↓

THE GUADALUPE RIVER PARK

It holds significant ecological value and is home to many wildlife species, including the Chinook salmon, rainbow trout, great blue heron and California beaver.

Understanding the trends and forces at play, SPUR focused its research on three main objectives:

Current River Conditions and Stressors

The Guadalupe River is continuously affected by a multitude of factors that have an incredible influence along its course. Both natural and human-caused, these forces affect the larger ecosystem of the river, including its flow and the habitats within, and along, its banks.

The Urban System

The urban system in San José neglects the river. The proximity of downtown San José to the river presents the challenges of impervious surfaces, ranging from building surfaces to vast concrete spaces, and insufficient treatment of runoff water prior to discharge. Pedestrian and bicycle connectivity is challenged by an exposed, auto-centric and occasionally industrial experience, with rail infrastructure to the west and poorly maintained trails along the river. Hot summer temperatures increase cooling demands in buildings, and challenge outdoor comfort levels. A generic and relatively hard surfaced public realm does little to encourage vibrancy and interaction once outside the primarily private properties typical of the downtown, and there is little to suggest proximity to the Guadalupe River. Taken together, the existing urban experience is disconnected and somewhat disorienting.

Flooding

Flooding events have historically flood areas of downtown San José and the downstream Alviso community. Currently, these events are mostly contained within the river channel, thanks largely to infrastructure projects that have been completed to mitigate flooding from the river. Back in 2004, under the direction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Santa Clara Valley Water District, a one hundred-million-dollar Downtown Guadalupe River Flood Protection project which consisted of three diversion channels and culverts in the river adjacent to downtown San José, designed to overflow during large events including a 100-year flood was completed. However, recent studies have raised concerns that flooding associated with more frequent storm events remains a threat due to climate change, and on-going modifications to the watershed.

Land Use and Zoning

Land use and zoning in the downtown area is currently dominated by commercial development and transit uses. Parks and green spaces are not well connected, isolating ecological habitat, presenting challenges for pedestrian continuity, and precluding opportunities to create green stormwater conveyance networks to capture and filter runoff. The Guadalupe River Park and connecting trails are largely framed by areas zoned for commercial, industrial, transit and downtown oriented development.

Urban Heat Island

Urban heat island studies indicate that downtown San José experiences a temperature 5-7ºF higher, relative to surrounding rural temperatures. During the summer months alone, there has been an increase of 1-3ºF in average monthly temperature for San José, relative to measurements taken 50 years ago. The term “Urban Heat Island” describes the tendency for urban development to increase temperature relative to pre-development conditions. Contributing factors include thermal mass and changes in albedo (color and light reflectivity) associated with materials such as asphalt and roofing membranes, de-watering via paving and drainage systems, and the removal of vegetation which plays a role in modulating temperature.

How might we begin to reimagine the river and park to respond?

In recent decades, many cities have gone to great lengths to bring back natural river process and function, drawing people back to the riverfront as an amenity. These projects range from highly urbanized environments dominated by human activity, to restored natural areas and parks that focus on habitat for wildlife.

Riparian system management should prioritize protecting areas in natural or nearly natural condition. The restoration of altered or degraded areas could then be prioritized in terms of their relative potential value for providing environmental services and/or the cost effectiveness and likelihood that restoration efforts would succeed.

The idea of “rewilding” the river simply means allowing nature to take over far more often than we do. That might look like any number of things: replacing hard infrastructure with soft infrastructure, reinstating river meanders, protecting certain ecosystems sites from harvesting and other man made involvement, allowing brownfield sites to grow wild after cleanup, and more pertinent to the case of the Guadalupe River - replacing concrete channels with naturalized and restored habitat that can support a diverse flora and fauna.

Repurposing Underutilized Parcels

Underutilized land, from unbuildable lots to rights of way and roadway medians, can play an important role in addressing stormwater and hydrology. When aggregated, these parcels amount to a substantial opportunity for managing stormwater runoff that would otherwise be discharged directly into the Guadalupe River. These areas can simultaneously expand the riparian corridor, increasing habitat and public access while addressing climate and stormwater challenges.

Stormwater and Flood Management

As cities grow, impermeability typically increases as well; paved surfaces, buildings, and other urban infrastructure replaces natural systems and processes. The resulting larger flood volumes alternate seasonally with lower summer flows. As these problems have grown, many cities - San José included - have attempted to improve or restore urban hydrology to a more tempered flow regime through green infrastructure initiatives that aim to retain stormwater, recharge local groundwater, and reduce the rate at which runoff is discharged to rivers.

Green streets, green parking lots, rain gardens, vegetated roofs, disconnected downspouts, permeable pavements, and soil amendments are implementable tools to improve water capture and soil infiltration at the scale of individual parcels. The Guadalupe River is a complex natural system nestled in an urban watershed. By modifying the adjacent urban fabric, the river and riparian zone can be expanded and made into a high performing system that can extend outwards into downtown San José.

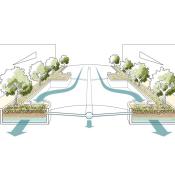

Bioretention and sub-grade soil systems shown are green infrastructure examples that have become common practice in California. Runoff collected from the streets of downtown can be directed into sub-grade soil systems and, via treatment and slowed conveyance, be directed into the Guadalupe River with improved water quality and flow patterns.

Shaping A Spatial Dynamic Between Community And Ecology

In order to truly promote the return of ecology and enhancement of habitat, we need to encourage the protection and conservation of natural areas. By doing so, we will create environments that are more rich and enjoyable for the public to visit. The complete removal of people from the river is socially unfeasible and detracts from our thesis of viewing the river as an asset, we propose creating protected nodes along the river dedicated to ecosystem regeneration, alternated with a variety of social programs along the river that are tactfully located based upon local opportunities and constraints. By maintaining the economical and social values of the river, one can provide the public with access and with the river in multiple ways, led by various local entities.

San José is experiencing a housing crisis, leaving many individuals homeless across the region. Homelessness is not confined to the city, many have found refuge among its rivers and streams as a source of shelter and access to water – introducing significant amounts of trash, biological refuse, and bacteria into the water bodies. This significantly impacts the river’s water quality and the species living in and along the river that depend on it. It is crucial that the Guadalupe River remain uninterrupted by human activity - in targeted areas along the river - in order for species to thrive and biodiversity to be fully realized and resilient.

These spaces were not designed to be homes, however, and housed users voice that the presence of unhoused residents degrades public spaces, rendering them unwelcoming or even unsafe.

A majority of the public spaces in American cities were designed by generations of predominantly white male professionals. These designers worked from their personal experiences and assumptions, and often created spaces that prioritized one type of user: a white able-bodied man.

Over time, the rules and norms that developed within these spaces further prioritized and accommodated this white male user at the expense of others.

Through a partnership with the urban design firm Gehl and a number of local stakeholders, we began exploring how to best facilitate community dialogue about the key challenges that housed park users experience when visiting Guadalupe River Park, specifically homelessness and safety.

from: “The park will only be great if there are no homeless people in it”

to: “The park will only be great if we design for coexistence.”

We identified four facets that allow for coexistence to take shape:

& Equitable Development of the Park

In San José, given the significance of Guadalupe River Park’s size, central location, and potential value to diverse residents, workers, and visitors, downtown stakeholders need to pursue concerted efforts to create high-quality open spaces and adopt holistic planning, policy, and management initiatives that ensure that all communities can access the revitalized park.

Resource Library

Here you'll find a repository of all of SPUR's public information about the Guadalupe River Park, from reports to blog posts.

News Articles

- What Guadalupe River Park Can Learn From New York’s High Line (June, 2018)

- Lessons for Guadalupe River Park: Thinking Big Together to Plan the Los Angeles River (August 2018)

- Lessons for Guadalupe River Park: How D.C.’s 11th Street Bridge Park Promotes Inclusion (September, 2018)

- Lessons for Guadalupe River Park: Denver Plans for Economic Growth Along the South Platte River (November, 2018)

- Leading With Public Space: The Case for Guadalupe River Park (January, 2020)

Public Programs

- Drawing the Future of Public Space in San José (September, 2018)

- Exploring One of San José’s Most Important Public Spaces (August, 2019)

- What's Next for SJ's Public Spaces? (November, 2019)

- Connecting Downtown San José Through Public Space (January, 2020)

- Re-envisioning the Guadalupe River Park (June, 2020) [recording available]

- Learning from the Best: How Toronto's Experience Can Shape San José's Future (November, 2020) [recording available]

- A New Tool for Achieving Coexistence in Public Space (January, 2021) [recording available]

- A 'Bigger Picture' for the Bay Area (April, 2021) [recording available]

- The Future of the Guadalupe River is Just Around the Riverbend (August, 2021) [recording available]

Credits

Content

- SPUR's work on the future of the Guadalupe River Park is led by Michelle Huttenhoff (Planning Policy Director, SPUR), with support from:

- Sherwood Design Engineers (on Rewilding Guadalupe River Park)

- Gehl (on Homelessness & Public Space)

- James Lima Planning + Development (on Funding, Stewardship & Equitable Development)

Photography

- Unless otherwise indicated, all photography by Kara Brodgesell (Kara Brodgesell Photography)

Website

- Plan and outline: Michelle Huttenhoff (Planning Policy Director, SPUR) and Amanda Ryan (Public Programming Associate, SPUR)

- Website template design: Neelu Bhuman and Andrew Nicholson (Design of Neelu)

- Project management and layout: Noah Christman (Director of Public Programming, SPUR)

Special Thanks

SPUR's multi-year Guadalupe River Park initiative is made possible with generous support from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation and John M. Sobrato, and close collaboration with the Guadalupe River Park Conservancy.