Alleys serve many purposes and people, often all in the same space. They provide back access so that service vehicles and garages don't conflict with transit and pedestrians, and so that main frontages can be preserved for shops and lobbies. They provide affordable and quirky commercial spaces for small businesses. They reduce the scale of large blocks, bringing light and air into dense areas, and creating a humane physical and mental framework for walking — with shortcuts, variety, and interest. They provide intimate, slow-paced environments protected from the noise and traffic of arterials, where people can spill out into the streets. The most interesting alleys are those that mix back-of-house with front-of-house with the house itself. But above all, they're the nooks and crannies of the city. For me, the sheer promise of hidden-ness, mystery and a sense of the unknown glimpsed down every narrow side street is what makes the city intriguing.

However, alleys are under constant threat, including by development. Once "vacated" and sold, we can never get them back. The fine city fabric is lost, made coarser and consolidated into larger parcels with bigger buildings owned by fewer people. Publicly owned rights-of-way are our most valuable and flexible assets. Our modern standards and codes, too, challenge our ability to design and replicate the best of San Francisco. In areas with large blocks, particularly industrial areas, we need to require all new large developments to create new alleys in order to build the web of public paths that inspire and enable people to explore on foot.

1. Quirk and fabric. At six feet wide, Elim Alley (above) is about the narrowest right-of-way in the city. You can almost touch the buildings on both sides. It reminds me of the Callejon de los Besos in Guanajuato, Mexico, so-named because lovers can lean out of their windows across the public way to kiss. Easily overlooked artifacts of space are vulnerable — this alley may be threatened or celebrated by a current proposal incorporating the parcels on either side.

2. Mess makes function. This Chinatown alley shows that informality and messiness can create a functional and humane place. Great places such as these give the standard-bearers the fits: it's impossible to fit the required sidewalks on both sides plus a separated roadbed plus space for trash cans, light poles, etc. Pedestrians dominate the space and everything else gently fits in.

3. Misapplication of standards. The re-designed Valencia Gardens was supposed to continue the pattern of great small streets in the Mission (e.g. Lexington Street, right), which have one lane of traffic and parking. But the Fire Department applied a suburban 20-foot drive width here, so we ended up with an overbuilt two-lane road that later required the installation of bone-jarring speed-bumps.

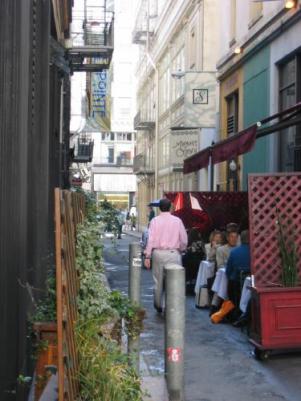

4. Get vertical and span the space. Alleys are perfect for creating a "roof" to the public realm with lights and decorations that span from building to building. Adding thin, lightweight elements overhead that don't block the sky — like these banners and retractable awnings on Mark and Claude Lanes — creates vertical interest and a human scale to draw people down otherwise foreboding and canyon-like corridors.

5. It's the small things that count. Trinity alley has been transformed into a successful lunchtime Financial District open space. Thin retail slivers that hold a hot-dog stand and poster store show that it doesn't take much to enliven a space! It's back-street businesses like these, not the premier restaurants, that make the city functional and affordable day-to-day.

6. Moderation and scale. Keeping alleys livable means maintaining sunlight as well as an appropriate scale. The Planning Department is crafting new height controls to require stepbacks and lower height limits along alleys. The Yerba Buena Lofts, while eight stories on Folsom Street, creates the right scale along Shipley Street by stepping down along the alley.

7. Erasing the public realm. Jessie Street. RIP. Nice wall, eh? Selling off streets to increase the size of development is explicitly prohibited in the General Plan, yet strong policies protecting the city's intangibles often lose out when officials are enticed by the economies of scale.

Caseworker: Joshua Switzky is a planner and urban designer in San Francisco.

Photo Credit: All photos by author.

[Urban Field Notes, an additive of cultural landscapes and observations compiled by SPUR members and friends, will now be a regular feature on the SPUR Blog. Urban Field Notes can also be found in the Urbanist, a monthly publication sent to all SPUR Members. Send your ideas to Urban Field Notes editor Ruth Keffer at editor@spur.org]