UPDATE: Governor Brown declared a drought emergency in California on January 17.

The governor is likely to declare a drought in California in the next few weeks, in response to consistent dry weather that has been affecting the state for over a year now. (The San Jose Mercury News has a good explanation of why this dry spell is happening.) 2013 was one of the driest years on record, with San Francisco, for example, receiving just 15 percent of its average annual rainfall. 2014 is not off to a great start either. Sierra snowpack — which provides water for about 25 million people in California — is only about 20 percent of normal, and the state Department of Water Resources has forecast that it will only be able to meet 5 percent of water supply requests from cities and farms this year. As we head into a third dry year, water conservation is more important than ever — and so is preparing for future uncertainty in our water supply by investing in reliable, sustainable supplies such as recycled water and potable reuse.

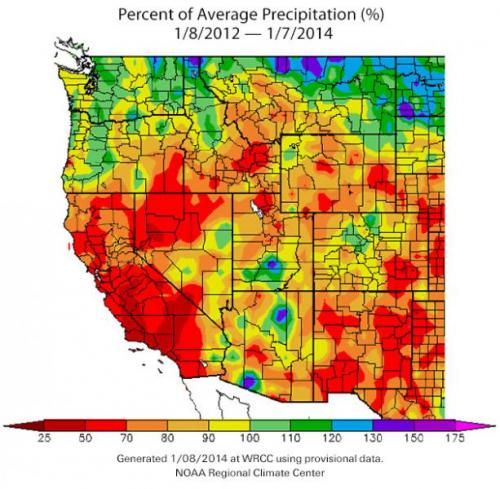

The last two calendar years have seen below-average precipitation in almost all of California. Source: California Department of Water Resources, http://www.water.ca.gov/waterconditions/

SPUR’s 2013 report Future-Proof Water describes water supply vulnerabilities in the Bay Area and recommends ways to reduce demand and augment supply. Without thoughtful planning, today’s water supply challenges will only worsen: Our region of 7 million people will add 2 million more by 2040. Our water demand as a whole will increase about 22 percent above 2010 usage by 2035, and demand in some places will accelerate even more rapidly. About two-thirds of the region’s water is imported from outside the region, so statewide water conditions are critical for us, too — not just for Central Valley farms and Southern California cities. And climate change — frequently cited as a culprit of the last two years’ uncommonly dry weather — may in the future significantly affect both the availability of supplies and our ability to store it.

It takes many years to build new water supply facilities, which means the Bay Area should use this second dry year as a chance to prepare for water uncertainty in the future. Optimizing for reliability, cost-effectiveness, and environmental impact, here are some of the best tools we’ve identified to improve water supply reliability to our region:

Managing Demand

These tools are typically the most cost-effective and reliable, and have the lowest environmental impact.

- Conservation and water efficiency. Reducing water waste through incentives, rules and education, have grown increasingly important to urban water agencies in California over the last 20 years. Most water suppliers view conservation as an investment in reliability and even consider conservation savings as a source of future water supply in their long-term portfolios.

- Metering of all water connections is considered a best practice in urban water conservation in California. It enables measurement of individual customers’ water use, and volumetric pricing, so that water bills reflect levels of consumption.

- Pricing water use provides a powerful economic incentive for conservation. Although demand for water is relatively inelastic, it is not unresponsive to price. On average, a 10 percent increase in the marginal price of water can reduce urban residential demand in the U.S. by 3 to 4 percent. The ideal rate structure to create an incentive for conservation is a multiple-tiered structure, where higher volumes of use command higher per-unit prices.

- Water budgets are a way of benchmarking individual water use and charging customers more per unit for water used above their budgeted amounts. (On the downside, they’re complex to administer.)

- Green building programs can create incentives in new construction or major retrofits to achieve water savings beyond code requirements.

- Compact development. Low-density development, like single-family houses, uses more water than high-density development, such as apartments and condos, largely because of increased outdoor water use.

- Retrofit on resale ordinances require that all water fixtures in a building meet certain plumbing code requirements before a deed is transferred in a sale. Such rules can accelerate the pace of projected conservation savings.

- Water demand offsets require a developer to not only build water-efficient new development but to fund retrofits elsewhere in the service territory to result in water “neutrality,” i.e. having a neutral or positive impact on the region’s water supply. Negotiated on a case-by-case basis, this tool aims to result in a “zero water” footprint for new development, meaning that the development saves as much water as it uses through a combination of on-site and off-site investments in water efficiency.

- Reducing system losses. Upgrading older infrastructure and keeping water distribution systems in a state of good repair are good practices to save water by cutting unnecessary and wasteful leaks.

Developing New Supplies

New water supplies have tradeoffs in terms of cost-effectiveness and environmental impact, but some are better than others. In rough order of least-to-most downsides, here are the tools we found relevant for the Bay Area:

- Conjunctive use is a type of groundwater banking strategy that manages groundwater and surface water together. During wet years, conjunctive use puts extra imported water into a groundwater basin, letting the aquifer recharge while serving as a storage reservoir. In dry years, higher pumping rates can occur without unsustainably mining groundwater.

- Groundwater extraction is considered a relatively sustainable source of water supplies when extraction rates do not exceed recharge rates, and when extraction itself does not contribute to worsening water quality in the basin.

- Direct and indirect potable reuse are two ways to treat and reuse highly purified wastewater. These types of projects produce water that is drinkable and more highly treated than recycled water.

- Banking and transfers. Water banking refers to a suite of transfer and storage tools that enable multiple buyers and sellers to legally exchange various types of surface, groundwater and storage entitlements. Transfers, which may involve more direct leasing or purchase contracts between suppliers and users, are a growing tool to supply urban users in California.

- Onsite reuse and district-scale systems. Onsite water reuse systems are a type of water recycling that can be permitted at the site scale and can save between 20-75 percent of potable water demand in mixed-use and commercial buildings. District-scale water recycling, detention and treatment systems are an opportunity in the future to reduce stormwater flows and augment supplies in dense urban areas and new large campus-type developments.

- Recycled water is highly-treated wastewater that can be used for landscape, industrial, agricultural, environmental and other beneficial but non-potable uses.

- Desalination commonly refers to the production of potable water from seawater. The costs to produce it, and the environmental impacts of such production, are highly specific to individual sites and projects.

- New surface water. There is very little “new” water for Bay Area utilities to develop, but building new surface storage and increasing the size of existing reservoirs is an area of active exploration and planning.

All of these options will help us avoid future rationing, an emergency measure that is already being implemented in parts of California that do not have reliable dry-year water supplies. There is no one-size-fits-all prescription for water security, because cities and water agencies in the region have such different water supply portfolios. But since it takes many years to study, plan, permit and construct water supply facilities, it is not too early to begin planning for water supplies for the next drought — and the next 2 million people. And let’s not neglect our most important near-term strategy: praying for rain.

Resources:

For more about this year’s drought, and the history of droughts in California, read a helpful FAQ from the California Department of Water Resources >>

Learn more from KQED's comprehensive Drought Watch coverage >>

Read SPUR’s report Future-Proof Water >>

Read SPUR’s analysis of San Francisco’s water supply diversification plan >>