It takes tenacity to cross the Bay Area on public transit. Take the trip from U.C. Berkeley to Stanford: important destinations that are both inherently walkable places with daytime populations in the tens of thousands. It’s logical to think they’d be linked by high-quality transit connections. But even during the morning rush hour, this trip takes nearly two hours, three different transit vehicles and good wayfinding skills at every station.

This is just one example of how trips in our region are made difficult when they require traversing multiple transit systems. The Bay Area is infamous for having 27 transit operators, but that fact obscures the many other kinds of transit fragmentation we experience: different maps; different apps and web sites; different names for transit services (“local” or “rapid” mean different things in different places); different types of signs and wayfinding at stations; different schedules and frequencies; and different amenities on each service. Parking is priced differently for different park-and-ride locations, bike parking options change from station to station, and what is depicted as a direct connection on a map doesn’t feel like one once you arrive.

Palo Alto Station, one of the two transfers required along the two-hour ride from U.C. Berkeley to Stanford via BART, Caltrain and local bus. Photo by Zack Dinh

Determined transit users, or those with no other option, have gotten used to the difficulty. Many others simply opt out and jump in a car rather than decode complex transit information and deal with uncertain transfers. New web- or app- based mapping tools are a real leap forward in trip planning. But nice maps don’t solve the problem of physically getting around the region.

Our best transit is not always located where it’s needed most. Popular lines are at capacity while near-empty rail cars and buses are an every day occurrence on other lines. The private sector is increasingly paying for shuttles or private carsharing to provide their employees with transit services that don’t otherwise exist. Certain trips will never make sense for the public sector to provide, but in many cases, our system hasn’t figured out how to keep up with demand.

Tackling Transit Fragmentation

SPUR recently hosted a charrette to look at how we can make the region’s many transit operators function more like one system. Transit operators, regional planners, transporation experts and private transportation providers, among others, gathered to share what we have learned from the past and where the opportunities lie. The charrette was part of a current SPUR project to identify practical approaches to making the region’s transit function like a true network.

We asked participants to envision the system in the year 2025 and think about solutions to five questions:

1. How can we make the transit system more legible? This group discussed the importance of dignity when traveling by transit, having a sense of place throughout the system and adopting an entrepreneurial mindset about service design. Potential solutions included creating a shared look and feel across transit maps and developing targeted marketing for different riders.

2. How can we better coordinate and connect service between operators? Group 2 discussed the many ways to make transfers between operators more seamless, such as coordinated schedules, consistent or integrated fare structures, coordinated service planning and way finding, and solving the “last mile” problem. They prototyped a regional fare structure, developed ideas for more consistent signage at stations and suggested an incentive system to improve on-time connections.

3. How can the transit system better respond to demonstrated demand? This group identified a role for cities to help shape transit services to match demand, as well as a need for transit to be seen as an asset in cities. Participants suggested developing better metrics for success that could be tied to funding, as well as piloting innovative transportation services in low-density areas that are hard to serve.

4. How do we prioritize the most important transit investments as a region? Group 4 focused on the need for better regional funding for transit and creating tools to incentivize or support more seamless transit. Participants identified the need for champions to advocate for long-term solutions and sustainable regional growth.

5. Where are the gaps in the network? This group identified all kinds of gaps — not just gaps in the transit network. These included gaps in last-mile solutions, gaps in the job-housing balance (which leads to empty transit seats), gaps in physical integration at stations, gaps in high-quality transit-oriented development and even gaps in funding tools. (For example, could grants to build parking structures be used to operate transit if the structure isn’t built?)

Mergers and acquisitions of transit operators is always a popular topic, and we are certain there are instances where that would make sense today or in the future. SPUR is working to determine the criteria for which moves should be made, and when.

Growing Around a System

It also takes tenacity to build neighborhoods — and grow a region — around reliable, world-class transit. SPUR and others promote growth focused on transit neighborhoods: places where you can meet a variety of needs by foot, bike or transit. But what happens to a transit neighborhood when the transit doesn’t have a stable funding source? Or if service only runs some parts of the day?

It’s hard to imagine great regional planning without agreeing on a cohesive core transit system to organize it, but that is essentially what we have been doing in the Bay Area. If we look at all the services together as one system, we can make better decisions about which parts need investment — and what kind of investment.

How Much Does Transit Cost?

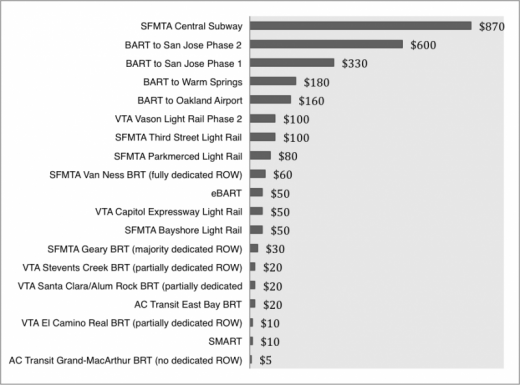

Capital cost per mile (in millions of dollars) of different transit technologies

Click to enlarge chart >>

Are we choosing the right transit technology for each corridor in the region? Source: Metropolitan Transportation Commission

Thanks to the determination of many leaders, we have made some progress on making the system more cohesive. The Clipper fare card, which allows payment on eight transit operators and will soon expand to seven more, is the biggest accomplishment. Bay Area Bike Share is a promising example of shaping a transit service to be uniform across the region. But at the same time, new choices like local shuttles and ridesharing are increasing the fragmentation.

Charette Group 1 considered ways to make the Bay Area's transit network easier to navigate.

Creating a Seamless System

In the coming months, SPUR will take the many ideas developed at the charrette and workshop them with stakeholders including cities, transit operators, riders and potential riders, the private transportation sector and regional agencies. We will also identify the best places and times to pilot changes. Plan Bay Area’s performance targets, and climate change laws like Senate Bill 375 and Asembly Bill 32 give the region a healthy mandate to design our transit network to produce real travel behavior change. Some windows of opportunity may open when a new transit service is planned, when an agency draws new maps, or when county or regional agencies undertake the planning and programming of funds. Stay tuned for our recommendations this fall.