How can we get past stagnant partisan arguments about climate change and begin looking at its impact on economic planning and investment? Kate Gordon of Next Generation presented this question at a SPUR lunchtime forum on the Risky Business Project, a nonpartisan effort to quantify and publicize the economic risks from climate change impacts.

Gordon, the executive director of the project, said the goals were two-fold:

- Lead a nonpartisan, business-focused national conversation on the risks of climate change to the U.S. economy

- Provide credible, actionable data so public and private sector decision-makers can incorporate climate risk into everyday planning

A committee of high level business and political leaders led the project; co-chairs were former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, former United States Secretary of the Treasury Henry Paulson and investor and philanthropist Tom Steyer. By framing the issue around risk, rather than previous approaches like cost-benefit analysis, the authors aimed to present the problem in a language that business people would immediately understand.

The final report covered every region of the United States and selected a few sectors where historical climate science data could be statistically analyzed to predict future economic impacts. These sectors were agriculture, energy demand, coastal infrastructure, labor productivity and public health.

The report’s results were a mixture of positive and negative impacts. The researchers found many negative economic impacts of staying on a business-as-usual emissions path. However, these negative impacts were highly localized: Gordon noted the importance of telling regional stories instead of averaging results nationwide, which would have led to some negative impacts being masked by positive changes elsewhere.

Coastal cities on the Eastern Seaboard and the Gulf of Mexico will have the greatest economic impacts from damages caused by coastal storms, hurricanes and sea level rise. San Francisco, despite its coastal positioning, is at much lower risk from sea level rise than other U.S. cities.

Overall increases in nationwide temperature will raise energy demand in most regions, with the Southwest and the southern Great Plains taking the brunt of the impact. Higher air conditioning use will require up to 95 gigawatts of new power generation, or approximately 200 new gas or coal-fired power plants.

The agricultural sector results demonstrate the importance of looking at impacts regionally. Averaging results nationwide would indicate little change, but the story is much more complex at a finer grain. For example, many Midwestern and Southern counties may see their yields decline by as much as 20 percent without adaptation, while areas farther north and west may see yield increases due to warmer temperatures and higher levels of carbon in the air. In California, some areas will see productivity declines of more than 20 percent, while other areas will see increases of up to 10 percent.

Changes in national temperatures will have enormous impacts on both human health and labor productivity. There will be an extreme increase in the number of days over 95 degrees, with the southern regions seeing the largest increases. In California, the number of these days will double or triple.

There will also be an increase of days surpassing a threshold on the Humid Heat Stroke Index (HHSI), which is a function of both heat and humidity. Above a HHSI of 95 degrees (approximately an outside temperature of 108 degrees F and a dew point of 95 degrees F) exposure to the outdoors for longer than about 20 minutes can result in heat stroke and even death. The country has never before experienced a day with this type of extreme heat and humidity. By late century, the Midwest could see up to two of these days per year, and up to 20 per year by the following century. The southeast could see up to 36,000 deaths per year from heat-related mortality, or approximately the same number of annual deaths from auto accidents.

Outside worker productivity across the country could fall by as much as 3 percent in some industries, which is the equivalent of losing the entire Connecticut labor force. California will see labor productivity declines of up to 1.6 percent. Minorities, especially Latinos, make up a proportionally greater portion of the outdoor labor force, raising equity issues on top of the health and productivity concerns.

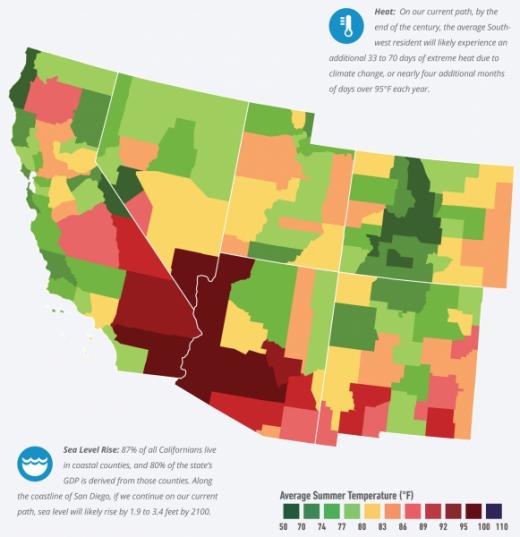

Average Southwest Summer Temperature by 2100 and Key Impacts

The biggest impacts to California will be in increased temperatures and rising sea levels. San Francisco, however, will see less extreme changes than other parts of the state. Source: Rhodium Group.

The Northwest appears to be the region that will emerge most unscathed from climate change. According to Gordon, “the biggest risk to the Northwest is that everyone is going to want to move to the Northwest.” She noted that the Northwest may also see larger impacts from increased fire risk or ocean acidification, neither of which were modeled in the report.

At the end of her presentation, Gordon stressed that these extreme impacts are not set in stone. We can still mitigate emissions and avoid risk, but we need partners in the business world to accept the economic risks and make adaptation and mitigation a part of their everyday decision-making processes.

Read the Risky Business report >>

Explore SPUR's work on climate adaptation >>