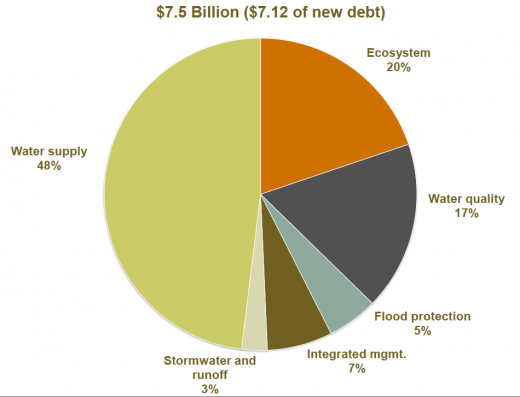

This November, after years of intense stakeholder negotiations, expanding and contracting, going on the ballot and then coming off again, being specific about projects and then becoming vague again, Proposition 1 — the latest in a decade-long series of state water bond issuances — will be decided by California voters. Prop. 1, the Water Quality, Supply and Infrastructure Improvement Act of 2014, is a $7.5 billion general obligation bond placed on the ballot by a near-unanimous legislative vote and the governor’s signature. It would fund water supply, ecosystems, water quality, groundwater cleanup, conservation, recycling and reuse — and it would complement the funding that local governments and water districts provide (in far greater amounts) for water projects and flood protection. Prop. 1 is also intended to help close an identified gap of water system needs and available funding, which is as much as $2 to $3 billion annually just for flood and stormwater management, small drinking water systems, and ecosystem support.

Figure 1. What Does Prop. 1 Fund?

Source: Public Policy Institute of California

Source: Public Policy Institute of California

Unlike the nearly $20 billion in other water bonds that voters have recently approved for water, Prop. 1 devotes its biggest chunk of resources, $3.63 billion, to water supply. Within that piece, 75 percent is appropriated to water storage, which is also the most controversial aspect of the bond. New storage facilities for water supplies are controversial because they almost always involve dam-building, land inundation and diversions, which negatively impact river environments and ecosystems. Although the bond money would be allocated by the state Water Commission in a competitive process and may only be used for the “public benefits” of water storage projects — such as recreation, flood protection and ecosystem restoration (and not for the storage projects themselves, which must be paid for by ratepayers) — Prop. 1 is opposed by some environmental and recreation groups.

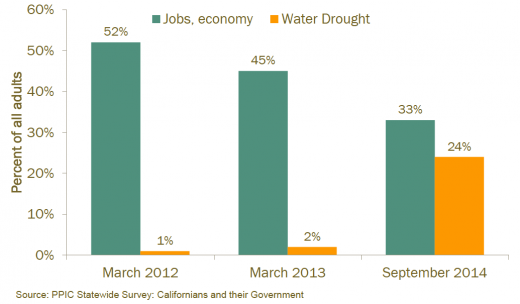

On the other hand, as we discussed in our 2013 report Future-Proof Water, new storage facilities enable water agencies to capture more of the benefits of water transfers, wet years and new supplies like recycled or desalinated water. Expanded storage facilities could also help manage climate change impacts by providing additional storage for heavy rains and capturing more of the precipitation that may fall in the Sierras as rain rather than as snow, due to climate change. With the utter lack of rain this year, Prop. 1 probably faces good political odds that voters will want to pay for public benefits associated with new storage facilities. The bond funding could improve the likability of those projects, and provide resources to mitigate their negative environmental impacts.

One major change between the 2014 bond and its previous incarnations is a lack of any appropriations specific to the Bay-Delta, a linchpin of the state’s water conveyance system and an ecologically fragile area. The Bay-Delta Conservation Plan, a 50-year plan to meet water supply reliability and ecosystem restoration goals, which is now undergoing environmental review, looked to state bond funding at least in part to pay for some of the restoration work that is to be publicly funded under the plan (the “twin tunnels” part of the project would be funded by ratepayers). This plan is controversial because of a long-held belief by some residents that continued water diversions in the Delta, even at the same levels as today, will hasten its demise. By making the bond “Delta-neutral” in order to win political support, Governor Brown has probably neutralized some potential opposition to Prop. 1, but he may have made the challenge of finding public funding to restore the Delta even more difficult.

Two other appropriations within Prop. 1 provide new funding in underresourced areas and represent an opportunity for the Bay Area: $725 million for water recycling and reuse, and nearly $1 billion for groundwater projects and cleanup. New state legislation requires local agencies to manage and plan for their groundwater resources but does not provide additional funding — a gap this bond could help fill. During this year’s drought, statewide groundwater use has increased from 40 percent to 60 percent, and until now there has been no requirement to manage the resource in a sustainable, planned way. That should change within the next five years, and bond appropriations could be helpful.

As a March 2014 report from the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC) describes, even if Prop 1 passes, our water system still faces funding gaps, and California needs to increase its financial commitment to the system from all sources by 7 to 10 percent to close structural funding gaps. With support from the federal government diminishing, and local agencies facing hurdles to raising local funds (such as Prop 218 and Prop 13), bond funds are a key piece of what California can offer. However, they are a one-time source, and with debt repayments now nearly at the same level as annual bond spending, there is a limit to how much more we can do. PPIC recommends that in a post-bond era, we need new fees and taxes at the local and state levels, more funding authority for local agencies to manage stormwater and groundwater, and even constitutional reforms to allow modern water management practices and remove barriers to funding. Perhaps the severity of the drought is providing a window of opportunity to make reforms, such as the historic legislative package on groundwater that passed last month.

Figure 2. What Californians See as the State’s Top Issue

SPUR does not take positions on state ballot measures; we focus our ballot analysis and Voter Guide on San Francisco measures. But since we do work on local and regional water policy, we felt it was important to provide a brief analysis of Prop. 1, as it has implications for the Bay Area. Let us know if it helps you decide — and don’t forget to vote on November 4, or sooner.