For decades, San Francisco and other high-cost California cities have added fewer homes than needed to accommodate all the people who want to live in them. Adding fuel to the fire, San Francisco has added over 50,000 jobs in the last four years and is growing by approximately 10,000 new residents per year. With statistics like those, even the city’s current housing “boom” of approximately 3,500 units per year in 2014 and 2015 (compared to an average of 1,750 per year over the prior twenty) can’t go far in solving the crisis.

There are 3.3 million low-income households in California, the majority of which spend more than 50 percent of their income on housing. Most of them will never have the opportunity to live in a high-quality subsidized affordable housing unit like the ones that nonprofits build and manage in San Francisco. Nor will they be able to access one of a shrinking number of housing vouchers provided by the federal government. How do we help the vast majority of low- and middle-income residents who cannot access these benefits?

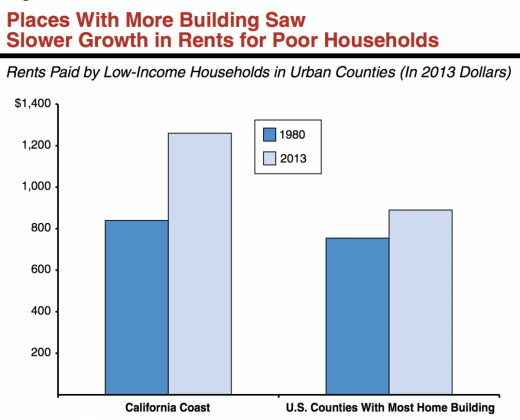

A new paper from the California Legislative Analyst’s Office provides evidence that market-rate housing construction plays an important role in housing affordability for low-income households. In this follow-up to last year’s California’s High Housing Costs: Causes and Consequences, the LAO shows that urban counties nationwide with more housing construction had slower rent growth than California coastal cities.

California Legislative Analyst's Office

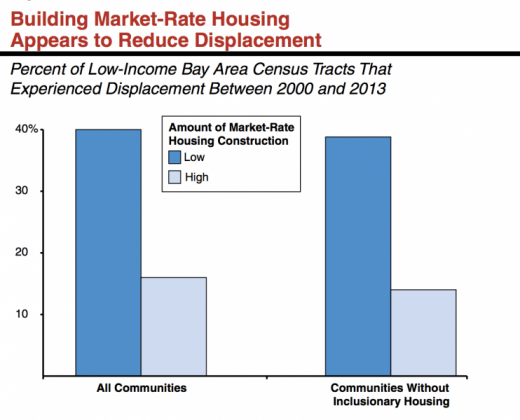

In the Bay Area between 2000 and 2013, census tracts with more market-rate housing construction experienced significantly less displacement of low-income households than those with the least construction.

California Legislative Analyst's Office

As SPUR has long argued, to address this crisis San Francisco and cities like it must plan for dense growth in the right places, dedicate significant funding to subsidized housing for those with the most need, pursue innovations that could address the needs of the middle-class as well as lower-income households, and allow robust production of non-subsidized, market-rate housing. It won’t be easy, but growing the overall supply can reduce the strain on our existing housing— and the resulting displacement pressures that many low-income households face.

Read the LAO's Report >>

Read more from SPUR and others in the Washington Post >>