Phase II of the BART Silicon Valley extension — a 6-mile, four-station extension of the BART system in San Jose and Santa Clara — is moving forward through the planning, engineering and environmental review processes. The City of San Jose and the Santa Clara Valley Transportation Authority (VTA) Board of Directors will vote on their “preferred project alternative” in the next few weeks. There are three major decision points:

- Should the downtown BART station be located to the east or to the west?

- Should the BART station at Diridon be located to the north or to the south?

- What type of tunneling method should be used to construct the BART tunnels and stations downtown and at Diridon?

BART is going to shape San Jose and the south bay for a long time, opening up new labor markets, stimulating and supporting housing and job growth, and giving people better ways to get where they need to go. While SPUR isn’t taking a position on all three of these decision points, we offer a few ways to think about each of the options.

1. Should the downtown BART station be located to the west or to the east?

There are two choices about where to locate the downtown BART station. SPUR has been an early and vocal supporter of locating the station to the west, on Santa Clara between Market and Third streets (rather than between Third and Seventh streets). Our support for the west option is based on the following key principles:

• The station should be located in the place that will maximize the number of riders. There are more potential riders within walking distance of the west option, and this will continue to be true in the future, with 58,000 new jobs and over 14,000 housing units planned nearby.

• The station location should help support economic development. Areas that are transit rich are more attractive to employers, so bringing BART downtown can stimulate job growth. The west option offers more support for job growth: more large parcels, more existing commercial buildings and more potential for clustering businesses.

• The station location should promote quick, direct and intuitive connections between different modes of transportation. The west option offers closer and more direct connections to buses and light rail.

2. Should the BART station at Diridon be located to the north or to the south?

There are two options for the location of BART at Diridon Station: to the north (along or under Santa Clara Street) or to the south (mid-block, south of Santa Clara Street and north of San Fernando Street). This decision is hard to make in isolation. Diridon is going to be home to many different transportation modes, and remaking Diridon has to be considered as one project — not a series of discrete projects that happen to be located near each other. To that end, it’s important to consider:

• The station location should promote quick, direct and intuitive connections between different modes of transportation. The city, VTA, Caltrain and the California High-Speed Rail Authority have committed to taking a fresh approach to planning for a truly intermodal station at Diridon. The placement and physical design of high-speed rail, light rail, bus facilities and bicycle facilities have not been finalized. Therefore, we don’t know which option will offer the best connections between modes.

We recommend moving forward with the BART decision, but we encourage all of the stakeholders to launch a process to create an integrated plan and vision — and do it soon. Each approach identified through this visioning process should demonstrate the ease of connections between modes and provide a circulation plan that addresses how to get pedestrians, bicycles, buses, shuttles, and services like Uber and Lyft to and through the site and station.

• The station should contribute to an integrated, walkable public realm activated by ground-floor uses. City staff recommends putting the BART station to the north, under Santa Clara Street. Today, Santa Clara Street is a wide, auto-oriented arterial that’s not very friendly for people who walk or bike. That has to change, especially if BART (or other transportation facilities) locates to the north.

If the station is to the north, the station entrances will be located along Santa Clara. This means the street must become a pleasant and safe place to walk and bike, lined with storefronts and businesses that attract people at all times of day and night. This will not only help encourage people to use transit, but it will also help to disperse the crowding that may occur at special events — such as concerts and hockey games at the SAP Arena. Given the proximity of the arena to the potential station and station entrances, it will be important to draw people in many directions. Walkable streets with destinations that disperse the crowds will promote safety and comfort — and can support retailers and restaurants nearby.

And this shouldn’t stop at Santa Clara Street. Some of the best stations in the world, such as Rotterdam Centraal, are surrounded by entire districts that limit driving and promote walking and biking. This is different than typical American stations, which typically emphasize connections via one or two complete streets. We need to be thinking about walkability at the district scale if we are to truly reshape San Jose.

3. What type of tunneling method should be used to construct the BART tunnels and stations downtown and at Diridon?

SPUR recognizes that there are pluses and minuses of both tunneling options. We offer a few ways to evaluate the tradeoffs of each construction method.

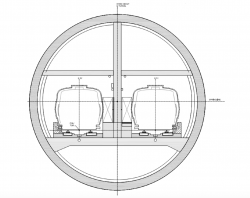

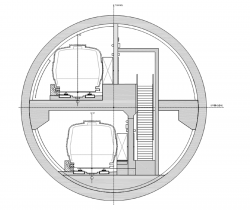

There are two different tunneling methodologies under consideration: double bore and single bore.

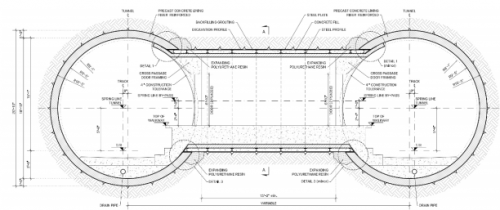

In a “double bore” tunnel, a tunnel-boring machine creates two parallel tunnels in which trains run side by side, joined by a center platform. The station and platform are constructed using cut-and-cover methods, which excavate a shallow trench and then build a roof over it, creating a significant amount of surface disruption (e.g., road closures, noise and impacts to businesses). The platforms are located 55 feet underground, compared to about 85 feet underground for single-bore construction. This is how every other BART station was constructed and configured, and it is the most common tunnel construction practice worldwide.

In a “single bore” tunnel, a large tunnel-boring machine drills a tunnel deep underground and the trains are stacked atop each other. Barcelona’s Metro Line 9 is the only system in the world to use a single-bore tunnel. With this method, more of the rail facilities, such as ventilation structures and stations, can be placed in the tunnel, reducing the need for cut and cover and minimizing surface disruptions (although some cut-and-cover work is still needed).

When considering each construction method, we encourage decision-makers to balance the following tradeoffs:

What are the financial risks?

All large tunnel boring carries some risk. Drills can get clogged with soil material (or there can be mechanical issues, as happened to Seattle’s Big Bertha). This can lead to unanticipated delays and cost overruns.

A particular risk with double-bore tunnel projects is that they can run into unforeseen utilities and ground conditions, driving up capital costs. A single-bore option allows the tunnel to bypass most of the utility infrastructure that is underground, potentially saving money and time. VTA estimates that a double-bore tunnel could cost $70 million more in capital costs than a single-bore tunnel.

Operating costs are also a concern. The rest of the BART system runs trains next to each other, not stacked. Having a single-bore tunnel in this one place would require some changes to how the system is operated, such as retraining train drivers for this new configuration and for new emergency procedures. VTA estimates that a single-bore tunnel could cost 2.8 percent more over 30 years compared to the double-bore tunnel. (Although the single-bore costs less in capital costs, that money most likely can’t be repurposed for operating costs due to restrictions on uses of funds.)

VTA is responsible for all of the costs of operating BART in Santa Clara County, and VTA’s budget is already very strained. The additional money needed for the single-bore tunnel’s operating costs would need to come from somewhere — either an existing funding pot or new revenue. We would discourage pulling the additional money for the single-bore tunnel’s operating costs from bus and light-rail service.

What are the political risks?

We can’t underestimate the importance of delivering BART to downtown San Jose in a timely way. If BART becomes embattled by cost overruns and controversy, it could slow down construction and even make future transit projects more challenging to build.

One of the main reasons why VTA is considering a single-bore method (and why the city supports it) is because it could have fewer surface disruptions — a good thing for local businesses. Many people in favor of the single-bore method remember the construction of light rail in downtown and are understandably eager to avoid negative impacts to local businesses once again.

However, BART is not the only project that will be under construction in downtown. Along with BART, Caltrain electrification, high-speed rail and potentially even a new Google campus at Diridon Station may be under construction. With so many projects going on at once, the single-bore tunnel’s smaller surface impacts may not make much difference on a day-to-day basis to downtown business owners, workers and residents: cars will be re-routed, trucks will be carrying debris off-site. For this reason, the reliable double-bore method shouldn’t be overlooked.

Which option will promote quick, direct and intuitive connections between different modes of transportation? Which option will create a safe and comfortable experience for riders?

We have to build stations that make it easy for people to choose and ride BART. The single-bore station doesn’t perform quite as well as the double-bore in terms of promoting intermodal connections and passenger experience.

A double-bore tunnel allows for a wide platform between tracks that is shared by people traveling in both directions. A single-bore tunnel requires a narrower platform that can only be used by people traveling in one direction, like this one in Barcelona. Practically speaking, the single-bore’s narrow platforms could feel crowded if there are a lot of riders (which we hope will be the case) or if there is a delay.

The single-bore tunnel is deeper than the traditional double-bore tunnel, meaning that platforms are far below the surface. This can be a disadvantage when it comes to station design and passenger experience: People have to go 85 feet below the street to catch the train (compared to about 55 feet for a double bore tunnel). This takes a long time and can be difficult to navigate, especially if transferring to other transportation modes.

A rendering of the downtown San Jose station in a single-bore configuration shows the depth and potentially disorienting nature of descending and ascending as much 85 feet. Image courtesy VTA, 2017.

A rendering of the downtown San Jose station in a single-bore configuration shows the depth and potentially disorienting nature of descending and ascending as much 85 feet. Image courtesy VTA, 2017.Arriving in downtown San Jose by BART could be disorienting. A rider would have to zig zag up a set of escalators, which can make it hard for people to get their bearings and determine which direction they need to go to reach their destination. The single-bore option’s depth isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker, but it would require sophisticated design and wayfinding to counter-balance these challenges.

Next Steps

With the final decisions planned to take place in January, it is time to take the long view — just as the elected officials who originally built BART did, just as those who decided to extend BART to Santa Clara County did. Bringing BART to downtown and Diridon has been decades in the making, and the outcomes of these three decisions will shape San Jose and the future of transit in the South Bay for decades to come. Let’s weigh them carefully.