As part of the SPUR Regional Strategy, we are looking at job trends and projections to help inform SPUR’s recommendations for creating a more livable, equitable and sustainable future for the Bay Area and Northern California. This article reviews data projections to 2030 in order to understand what types of jobs are growing and how the coming retirement wave will affect job openings. A related article looks at what types of jobs are growing and how low-wage jobs are faring relative to jobs at higher wage levels.

We highlight three key findings from our analysis of recent data and projections. (For data sources, see our note at the bottom of this article.)

- Given the low number of young people who will age into the workforce in the coming decade to 2030, the Bay Area will face a worker shortage as retirements surge. These jobs could be filled by immigration, domestic migration or in-commuters from the Central Valley — yet even the Central Valley will need new migrants to fill future jobs due to the limited number of new entrants into the workforce.

- While the number of middle-wage jobs will grow somewhat, most job growth will be in high- and low-wage jobs.

- Although retirements will provide a large source of job openings, there is evidence that automation may cut into the number of middle- and low-wage replacement job opportunities. Automation will meanwhile create some new job opportunities, but we know very little about what those jobs will be like or how many of them there will be.

This article looks primarily at data for the nine-county Bay Area and also considers data for the larger 21-county Northern California megaregion and for other metropolitan regions within it, including the Sacramento region, the Monterey Bay Area and Northern San Joaquin Valley.

Finding No. 1: The Bay Area and Northern California Megaregion will face a worker shortage as more workers approach retirement age.

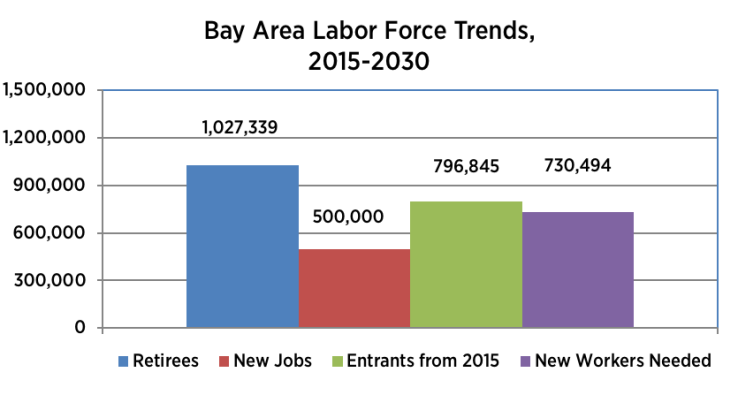

A coming surge in Bay Area labor force retirements will leave a potential worker shortage of more than 700,000 by 2030. This is because the combination of retirements and expected new jobs will outpace the labor force increase from today’s children as they become old enough to work. These retiring workers will be among the region’s most experienced and skilled workers. While new workers can acquire the necessary skills, the loss of experienced workers is an issue across many workplaces.

Filling this potential worker shortage will require increased foreign and domestic migration and/or in-commuting from adjacent counties. Given recent trends, immigration remains the most immediate source of new skilled workers (although the future of immigration is less certain in light of federal administration policies).

To ensure that more residents of the megaregion are able to fill the jobs of the future will require increases in the educational level of today’s children, a shift that takes places slowly over time. The other major challenges of high housing costs, housing shortages and long commutes also pose threats to finding new workers to fill the jobs of the future. Thus immigration, housing and transportation policies have major implications for our future workforce, along with education and training policies.

The chart below shows the projected changes to the labor force between 2015 and 2030. It highlights how the combination of retirees and new jobs far exceeds the new entrants to the workforce from children of current residents. This shortfall of over 730,000 workers must be filled by immigrants, domestic migrants or in-commuters.

For this analysis, we calculated retirees by taking the population in 2015, aging it 15 years and applying current labor force participation rates for each age group. The participation rates for each age group over 55 were increased in line with recent trends showing that older workers are working longer.

New entrants from today’s population were calculated by aging the 2015 youth population 15 years to show how many people will be 16 to 29 in 2030, then applying current participation rates. Bay Area job projections were developed by the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy.

The results reveal two trends. First, labor force participation rates fall sharply after age 55 even after accounting for older workers working longer. Second, the Bay Area population is aging, and a large share of regional growth to 2030 is in residents 55 and older. Retirements may be delayed, but they do happen eventually. The first chart below shows that labor force participation rates for older workers have increased in the nation, state and region, a trend expected to continue.

The next chart shows the sharp decline in participation rates between workers aged 25 to 54 and those 55 and older.

And participation rates fall within the over-55 age groups as people age.

This finding is important because most population growth — except in San Joaquin, Stanislaus and Merced counties — is in residents aged 65 and above.

The megaregion will need 1 million additional workers to meet the projected job growth as the number of retirees will be larger than the number of new entrants in to the labor force by 2030.

These projections include an assumption that older workers will remain in the workforce for a longer period in the future. It’s possible that economic conditions and improving health will allow for more labor force participation from all age groups in the future, however the Bureau of Labor Statistics projects increases for older workers only.

Finding No. 2: The number of low-wage jobs will continue to increase, and there is no likely surge in middle-wage jobs.

In general the share of jobs in each wage group (low, middle and high) changes slowly. Updated occupational projections are available for the state but not, as of yet, for counties in the megaregion. The projections for California are shown below.

Projected Job Growth in California, 2016–2026

| Wage Group | Projected New Jobs | Percent Increase |

| High Wage | 584,100 | 13.4% |

| Middle Wage | 462,400 | 7.6% |

| Low Wage | 885,800 | 11.5% |

| Total Jobs | 1,933,100 | 10.7% |

The projections show that there is no surge coming in middle-wage jobs. Jobs in middle-wage occupations have the smallest overall and percentage growth in projections released this summer by the California Employment Development Department. And at least a third of the projected job growth, especially in middle-wage jobs, will have already occurred by the beginning of 2019.

While the projected changes in the share of jobs in each wage group are relatively small, they continue the recent pattern, with gains in the share of high-wage jobs and declines in the share of middle-wage jobs.

Finding No. 3: While there will be a large number of job openings from retirement and people moving from job to job, some of these jobs are at risk from growing automation.

Job openings are the result of replacing a retiring worker, replacing a worker who transitioned to another job or where a new job is created. Looking ahead to 2030, most job openings will be from retirement (40 percent) and transitions (50 percent), not from job growth.

Most occupations with the largest number of job openings, and many with the most growth, are low-wage occupations with minimal education and experience requirements. In looking more closely at the job openings to replace retiring workers, the California Economic Development Department projects these openings are very important in slow-growing production and office sectors that will be impacted by potential automation. For example, the number of jobs in office and administrative occupations fell in the Bay Area during the past 10 years despite overall strong job growth.

High-growth, high-wage occupations are concentrated in health care and computing.

Automation trends will impact future job prospects. According to the McKinsey Global Institute’s report Jobs Lost, Jobs Gained, there will be a mix of job creation and job destruction from automation. McKinsey reports that workers in low- and middle-skill jobs will be impacted. One key concern is that job losses across particular occupations could take place at a speed that does not allow workers to become retrained or reemployed, even if there is significant overall job growth. McKinsey also reports that the pace of change will exceed that of historic transitions out of agriculture or industrial work in prior centuries. The key to managing the transition will be to ensure ongoing job growth and effective retraining programs that help workers, particularly those in midcareer, transition to new employment when their jobs are lost. Policy makers will have to be cognizant not to retrain workers for occupations that will be similarly threatened by automation in future decades. For example, in recent years many workers and military veterans received training to become truck operators — one of the occupational classifications most likely to be impacted by automation in the coming decades.

The coming waves of retirements and automation necessitate effective long-range planning and new forms of policy intervention to make sure workers are able to manage these transitions and can best benefit from new opportunities.

Notes on the data:

This article summarizes research prepared for SPUR on Bay Area and megaregion workforce trends. Bay Area data is for the nine-county Association of Bay Area Governments planning region. Data for the 21-county megaregion adds the six counties in the Sacramento Area Council of Governments planning region plus Monterey and Santa Cruz counties in the Association of Monterey Bay Area Governments (San Benito County data is not available) plus San Joaquin, Madera and Stanislaus counties in the San Joaquin Valley.

Data on labor force participation rates comes from the American Community Survey. Data on projected population growth comes from projections published in 2017 by the California Department of Finance. Data on state projected job growth by occupational group comes from projections published in 2018 by the California Employment Development Department. Job growth projections for counties outside the Bay Area came from the California Department of Transportation’s County-Level Economic Forecast.

About the author: Stephen Levy is director and senior economist of the Center for Continuing Study of the California Economy (CCSCE) in Palo Alto. CCSCE is a private research organization founded in 1969 to provide an independent assessment of economic and demographic trends in California. See www.ccsce.com.