Social vulnerability — the intersection of factors such as poverty status, race, age, disability, home ownership, and immigrant status — reduces the ability of individuals and communities to absorb and respond to a natural disaster. For example, low-income individuals enter disruption events, from losing a job to losing their home in an earthquake, with fewer resources such as financial savings to aid in their short-term and long-term recovery. In the Bay Area, due to historical and present-day practices of racial discrimination, those with high socially vulnerability are often concentrated in neighborhoods that have recently been identified as “equity priority communities” (census tracts with a significant concentration of underserved populations, such as households with low incomes and people of color). This designation helps local and state governments target planning projects to mitigate social, economic, and climate risk in these communities. When the next major earthquake shakes the Bay Area, these same communities, as well as vulnerable individuals living in areas outside identified census tracts, are likely to experience the greatest short- and long-term impacts, suggesting the need for integrated planning.

According to the US Geological Survey (USGS), there’s a 72% chance that the Bay Area will experience a magnitude 6.7 or greater earthquake in the next 30 years. In the event of a magnitude 7.0 earthquake on the Hayward fault –– modeled in the Haywired scenario — USGS Science Advisor Ken Hunt estimates that more than 400,000 people across the Bay Area could be displaced. In 1989, the 6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake killed 63 people, injured 3,757 and left as many as 12,000 homeless.

Because of its high seismic risk, large low-income population, and multiple equity priority communities, the City of Oakland amply illustrates the challenges policy makers must address in bringing an equity lens to their earthquake resilience efforts.

Mitigation Efforts Must Center the Needs of Frontline Communities

One of the most valuable paths toward community resilience in the face of the region’s next large quake is retrofitting the existing building stock, among the oldest in the nation, to resist collapse or serious damage. Bay Area residents of all income levels live in aging housing that is seismically vulnerable. Apartment buildings or single-family homes that do not meet current seismic safety standards will put residents in danger of injury, death, or displacement. These residences pose a post-earthquake housing instability risk for the socially vulnerable, especially elderly and disabled residents, who will require emergency shelter with specialized care and accommodations or otherwise be left to rely on the goodwill of friends and family.

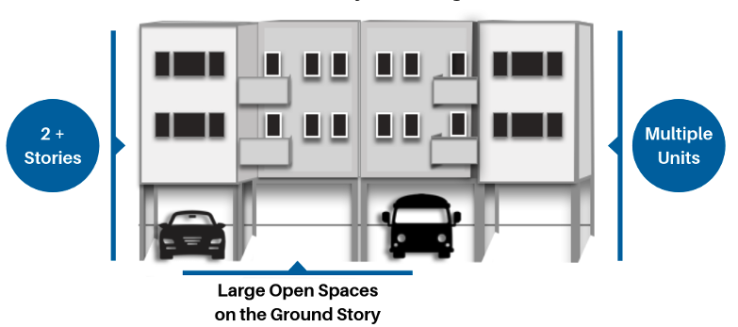

Soft-story wood frame buildings are one of the most ubiquitous and potentially unsafe residential building types in Oakland and across the Bay Area, though many other building types are also at risk. Soft-story buildings are those with large open spaces, such as storefronts or parking garages, on the ground floor. Without structural reinforcement, the buildings can suffer lateral damage or can even collapse due to earthquake shaking. In a 2014 inventory of its soft-story buildings, Oakland found that the buildings are likely to cause the greatest displacement of vulnerable residents after a quake.

Soft-Story Building Model

Click to zoom.

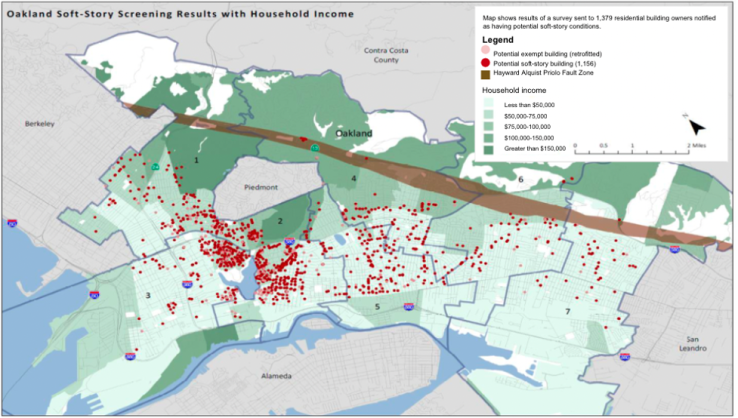

According to Oakland’s chief resilience officer at the time, soft-story buildings are most common in neighborhoods with relatively high rates of poverty –– often housing more occupants than average for their size and greatly contributing to the city’s affordable housing units.

Oakland Soft-Story Buildings and Household Income, 2014

City of Oakland soft-story buildings projected over household income by census tract, 2014. Most soft-story buildings that need retrofitting are in census tracts with annual household incomes less than $75,000.

Click to zoom.

In 2019, in response to the soft-story building inventory taken in 2014, the Oakland City Council adopted a soft-story-retrofit mandate. According to staff at the City of Oakland, the city has since advanced 158 soft-story retrofits, improving the seismic safety of 715 housing units –– a great feat considering the effects of the pandemic on renters and landlords. Unfortunately, some 900 soft-story buildings in Oakland still need retrofits. Without them, the city’s affordable housing stock could deteriorate in the next major earthquake, exacerbating the region’s housing crisis and taking a great toll on low-income residents.

Financing is a major challenge in advancing seismic retrofits, especially given today’s high construction costs and high inflation. Although retrofits for soft-story buildings are relatively low-cost (between $40,000 and $200,000), they can be onerous for small building owners who serve low-income neighborhoods. Furthermore, older buildings often have urgent maintenance needs that take precedence over seismic upgrades.

To incentivize retrofits, the City of Oakland used hazard mitigation grants from the California Governor’s Office of Emergency Services and FEMA to reimburse building owners up to 75% of project costs. This strategy reduced future rent increases for rent-burdened tenants, mitigating the effects of the city’s cost passthrough policy (70% of non-reimbursed construction costs can be passed onto tenants over the course of 25 years). The city is waiting for an additional $10 million from the state to continue the program.

In the Bay Area, only Oakland, Berkeley, San Francisco, and Fremont have implemented mandatory seismic retrofit ordinances. A few other cities, such as Alameda, have adopted voluntary ordinances, while others, including San José and Hayward, have conducted soft-story building inventories but have yet to adopt retrofit mandates.

Seismically resilient housing is critical to regional disaster recovery because keeping people in their homes reduces disruption and recovery time and maintains workforce and social networks.

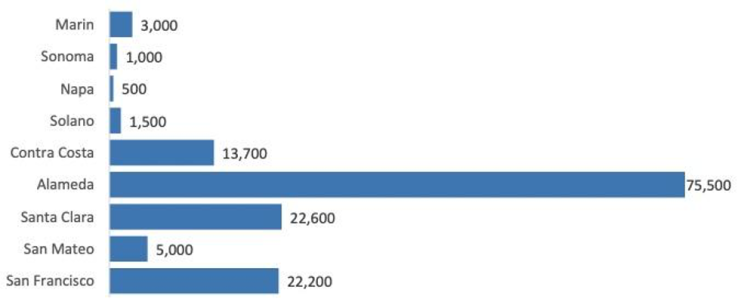

Households That Could Be Displaced by a 7.0 Hayward Fault Earthquake

Household displacement by county. A 7.0 earthquake along the Hayward Fault (USGS Haywired Scenario) could displace some 145,000 households by making more than 55,000 residential buildings uninhabitable. Alameda County residents will experience the highest rate of displacement with 14% of all households affected.

Click to zoom.

Disaster Response and Recovery Plans Must Prioritize Equity and Resilience — Across the Bay Area

After a major earthquake, many Bay Area residents will need to shelter in place or find emergency shelter. Lack of directed planning to advance the resilience of socially vulnerable populations will leave them without the requisite support. For example, residents who speak English as a second language or who do not speak English will have difficulty accessing and understanding emergency communications as well as accessing post-earthquake recovery services such as shelters and federal disaster assistance. Low-income residents will lack the financial resources to adapt and recover from an earthquake without state or federal support, and they are likely to find that government services such as food and water distribution are delayed due to power outages and road closures. For those living on CalFresh food assistance benefits, an earthquake that strikes at the end of a month, when groceries are running low, will be particularly burdensome. Undocumented residents will also be greatly challenged due to their ineligibility for federal disaster aid, making them dependent on state aid programs and resources provided by nonprofit aid organizations.

The recovery period following a major earthquake presents an important choice: either “build back better” — restructure communities to mitigate future hazard risks and create more opportunities for all to prosper — or maintain current practices and ignore existing vulnerabilities. At a moment when many residents might choose to or be forced to relocate, presenting united recovery plans developed through pre-disaster community engagement could offer a vision for increasing everyone’s sense of belonging throughout the Bay Area.

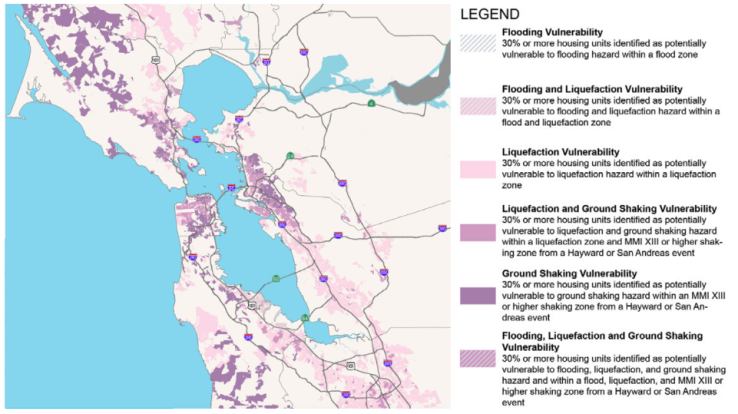

Regional recovery plans should provide guidance for rebuilding that takes into consideration long-term climate, earthquake, and other hazard risks. Across the Bay Area, high liquefaction risk zones overlap areas of future sea level rise and groundwater inundation. With continued sea level rise, liquefaction risk will become more extreme because saturated soils fail more readily during heavy ground shaking. In a major quake, equity priority neighborhoods in East and West Oakland, Richmond and San Francisco’s bayfront could see severe liquefaction damage such as cracks in roads and building foundations.

State and city officials, planners, engineers, community members, and other stakeholders must come together to take on the important and challenging questions posed by the future impacts of such risks: Do we prohibit rebuilding in zones with high seismic and climate risks? Do we plan costly infrastructure to protect these zones in the future? Or do we do nothing and allow business as usual? Furthermore, if we choose not to rebuild in some areas, how do we do so without further displacing frontline communities or exacerbating the region’s housing crisis?

Fragile Housing in Flood, Liquefaction and High-Shaking Areas

Click to zoom.

After Hurricane Katrina, private-interest developers took advantage of the devastated state of New Orleans by purchasing properties abandoned by the city and by homeowners without the means to rebuild. Thousands of public housing and affordable housing units were replaced by condos and townhouses, leaving displaced community members with few options and ultimately forcing many to permanently relocate to other cities.

The Bay Area can avoid a similar outcome if policy makers prepare policies and practices that readily direct recovery in an equitable way. For example, communities could designate targets for affordable housing or allocate funding to maintain small local businesses and critical services post-disaster. By developing recovery plans, we can make decisions about what we want our built environment and our communities to look like in the future and about how we will support our most impacted community members so they can remain and thrive in the Bay Area.

SPUR’s Earthquake Resilience and Equity Agenda

As SPUR revitalizes our efforts to advance earthquake preparedness in the region, community resilience and social equity will be central to our work. Earthquake resilience is not just about making our buildings and our built environment safer. It is about making sure that our communities possess the resources and opportunities to prepare, adapt, and rebuild in ways that are both community- and life-affirming. SPUR will advocate for policy and planning solutions such as local retrofit mandates, expansion of state-level grant opportunities for seismic upgrades, community-wide earthquake response planning, and region-wide long-range recovery planning that considers the challenges of earthquakes and other hazards while recognizing and mitigating the impacts of social vulnerability and racial inequity on community preparedness and resilience.

![Absence of adequate shear walls on the garage level exacerbated damage to this structure at the corner of Beach and Divisadero Streets, Marina District. [J.K. Nakata, U.S. Geological Survey]](/sites/default/files/styles/landscape_news_image_1x_tiny_/public/2022-12/007sr.jpg?h=853acb52&itok=7ZvLbmIN)