Public transit is an essential service for millions of Californians and is central to meeting the state’s ambitious climate, racial equity, health, housing, and economic development goals. Yet as one-time federal COVID-19 relief funds dry up, many transit agencies are facing a severe fiscal crisis. The state’s largest and most fare-dependent operators face financial challenges of a magnitude that could trigger severe service cuts and a spiraling decline. SPUR is leading a coalition urging the State of California to provide necessary funding so that transit agencies can keep buses and trains running as they work to transition to a financially sustainable business model.

California Has Bet Big on Transit

SPUR analysis of the National Transit Database (NTD) shows that in 2019 Californians took nearly 1.3 billion trips and traveled almost 8 billion miles using the state’s buses, trains, and ferries (equivalent to roughly 13% of all transit trips nationally and more than any other state in the country other than New York). The state’s more than 200 transit agencies range from small rural bus operators to big urban systems. According to the NTD, California is home to three of the country’s ten largest transit agencies. (As measured by ridership, LA Metro, SFMTA, and BART are the third, seventh, and tenth largest systems, respectively.) Transit in California is a major economic undertaking, with total annual operating expenditures of $7.2 billion in 2021, annual capital investments averaging just under $4.5 billion over the last decade, and employment of 32,000 direct workers and thousands more contract workers.

Transit remains a cornerstone of our social safety net and a ladder of economic opportunity, and it is critical to meeting California’s ambitious climate and sustainability goals.

Despite pandemic-related ridership losses, transit in California remains a cornerstone of our social safety net and a ladder of economic opportunity. In September 2022, California residents took more than 65 million trips aboard transit, up almost 40% from the prior year, albeit only 58% of pre-COVID levels. According to 2021 U.S. Census data, almost 60% of California residents who commute via public transit have a household income below $35,000. Deep cuts to public transit will disproportionately impact those most reliant on public transit: the state’s low-income and nonwhite residents and residents who do not own a car. These groups are more likely than other groups to count on public transit for their daily needs, including access to K–12 education and college.

High-quality, abundant transit is also critical to meeting California’s ambitious climate and sustainability goals. More than 40% of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions come from the transportation sector, primarily from cars. The state is already falling dangerously short of its statutory goal to reduce greenhouse gasses by 48% below 1990 levels by 2030. Making sure that people have the option to take transit to work, to the grocery store, or to see their friends is one of the most impactful policy actions the state can take to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The California Air Resources Board recently set a goal of doubling transit ridership to reduce emissions, improve public health, and support sustainable, compact growth — an ambitious goal that would have stretched the financial and operational capacity of the state’s transit agencies before taking into account their current struggles.

California is also depending on transit to support its vision for land use. Many of the recent legislative gains in addressing California’s housing crisis, such as SB 35 (Wiener), AB 2334 (Wicks), and AB 2097 (Friedman), have been focused on encouraging new housing near high-quality transit (generally defined as transit service at least every 15 minutes). Without robust transit service, fewer sites will be eligible for benefits such as increased density, reduced parking requirements, and anti-displacement protections that make it possible to produce more housing and increase transit access for people at all income levels. Developers will likely face more pressure to build parking, which adds costs and takes up valuable space that could otherwise be used for homes. Transit-oriented communities simply don’t work without transit.

A Crisis in Transit’s Business Model

California depends on transit, but the state’s ecosystem of agencies is lurching dangerously toward collapse. When the COVID-19 pandemic decimated transit ridership in 2020, one-time federal relief funds for transit operations insulated operators from bankruptcy and enabled them to sustain service. However, most agencies will exhaust these funds over the next several years.

Meanwhile, remote work trends and changes to commuting brought on by the pandemic have proven to be durable. In the Bay Area, the health of San Francisco’s downtown is directly tied to transit ridership: before the pandemic, nearly 70% of transit trips started or ended in San Francisco. Employer survey data from the Bay Area Council suggests many employers have settled into a “new normal” in which workers are commuting into the office only a few days per week, leading to fewer riders using transit and a significant, enduring loss of ridership and fare revenue (a trend that has been further exacerbated by a growing public perception that transit is unsafe). The magnitude of this impact is hard to overstate: overall, California saw a decline in total transit fare revenues from $1.8 billion statewide in 2019 to just $390 million in 2021, and although ridership and revenue have grown since, fares remain far below pre-pandemic levels.

Changing commute patterns, impacts to funding streams, and increasing operating costs are all challenging transit’s business model.

Further worsening the situation, some transit systems also rely on supplementary funding streams that are correlated with commuting. SFMTA, the state’s second-largest transit agency, has seen reductions in its revenues from parking and general fund transfers from the City of San Francisco (which is facing its own fiscal challenges related to office occupancy and other factors). On the cost side, nearly all transit operators have seen significant increases in operating costs driven by inflationary pressures and a particularly tight labor market that has made hiring and retaining workers incredibly difficult. In other cases, transit agencies like LA Metro and Caltrain are in the midst of long committed capital programs that will benefit riders and the public by electrifying vehicles and improving service but that will also result in increased operating costs.

Collectively, these issues amount to a serious crisis in transit’s business model. A recent study by the UC Institute of Transportation Studies found that more than 70% of California’s transit operators expect serious funding shortfalls when one-time federal dollars run out. This problem is particularly acute in the Bay Area, where the Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) anticipates deficits of $2.5 billion to $2.9 billion or more over five years, starting as soon as 2024. In Southern California, LA Metro, the state’s largest operator, is projecting large shortfalls beginning as early as 2024..

Without intervention, many of the state’s transit operators are at risk of slipping into a death spiral of service cuts, ridership loss, disrepair, and dwindling relevance. This outcome would be devastating to millions of riders and a tremendous blow to state and local policy goals. Decades of investment and effort to improve the state’s transit network would be undone.

Transit could collapse without state funding to help it attain a firmer fiscal footing.

Source: SPUR

California’s Biggest Systems — and the State’s Goals — Are at Risk

All transit in California is important and operators of all sizes are facing fiscal pressures related to revenue losses and escalating costs. The state’s many smaller transit operators provide important mobility options within the communities they serve and are essential to ensuring that all Californians can access essential transportation. But just as certain species play an outsize role in the overall survival and productivity of an ecosystem, California’s largest transit operators are particularly tied to California’s capability to meet its ambitious climate goals.

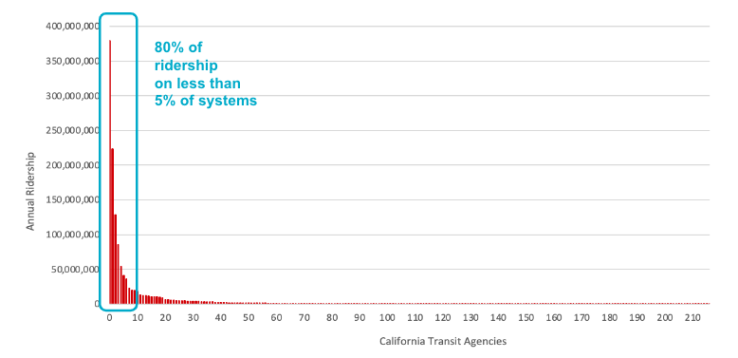

Of California’s 210 transit operators, 10 carry the vast majority of the state’s ridership.

Annual Ridership by California Transit Agency, 2019

Source: SPUR analysis of 2019 National Transit Database data

Of California’s more than 200 transit agencies, just 5% (10 systems) carry more than 80% of the state’s transit ridership. Of the five largest systems, four — LA Metro, SFMTA, BART, and AC Transit — are facing significant financial challenges and are projecting large operating deficits beginning in the next few years. With the exception of BART, these large operators were not hugely reliant on fares, but because of their sheer size, all have experienced large absolute losses of fare income that simply cannot be easily backfilled with other local revenue sources.

Like the largest systems, a number of mid-size systems that were formerly highly commuter-oriented and highly fare dependent are also facing severe financial challenges. Caltrain, Golden Gate Transit, and Metrolink have seen tremendous declines in ridership and are projecting significant future deficits. These specific systems also tend to serve customers who are traveling relatively long distances. (In 2019, according to figures reported to the NTD, the average Metrolink rider traveled more than 32 miles per trip compared with a statewide average transit trip of just more than 6 miles.) This means that, despite their relatively smaller ridership, mid-size systems are also particularly important and productive contributors to state goals related to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

California Under-Invests in Many of Its Largest Transit Systems

The importance of the largest systems to California’s declared goals for transit doesn’t match the level of financial operating support the systems receive from the state.

California provides significant funding to support transit operations through a series of programs, most notably, the Local Transportation Fund (LTF), the State Transit Assistance (STA) fund, and the Low Carbon Transit Operations Program (LCTOP) program. The Transportation Development Act, which was enacted in 1971, established both the LTF and the STA fund, which are generated by a portion of a general sales tax and a tax on diesel fuel, respectively. LCTOP was established by the California Legislature in 2014 and is funded with 5% of quarterly — and variable — cap-and-trade auction proceeds, which are deposited in California’s Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund. Funds associated with all of these programs are distributed by formulas based on geography and population and, to a lesser extent, on prior-year agency revenues.

For fiscal year 2020, LTF, STA, and LCTOP funds totaled approximately $1.8 billion, $670 million, and $64 million, respectively, on a statewide basis. The figures reflect information sourced from the California State Controller, the California Department of Tax and Fee Administration that was provided by MTC, and Caltrans. Tracking how and where this funding is actually used to support transit operations is surprisingly complicated. The California State Controller tracks use of funds but does not distinguish between operating and capital uses. (Many agencies use state transit funding for both purposes.) Similarly, although California transit agencies do report the use of state-sourced funding for operations to NTD, individual agencies vary in how they report LTF funds: some agencies code the source as state funding and others as local money, an inconsistency that is telling in terms of how this source of funds is viewed at the local level. Further complicating matters, LTF is the largest source of funds but it is not always used for transit, or transit operations. By statute, many smaller counties can — and do — use LTF to fund improvements to local streets and roads. Depending on location, LTF funds may be subject to complex distribution processes at the regional and local level that can result in widely varying funding outcomes for individual operators.

State funding makes up only a relatively small portion of the operating funding that California's largest and most productive transit systems rely on.

Transit funding is complicated, and transit agency budgeting approaches can be highly individualized and difficult to compare. Accurately tracking how state funding is used by Califonria’s transit operators en masse is challenging, but the relative amount of state funding specific systems rely on to support operations can be generalized by looking at both agency budgets as well as NTD reports. The table below illustrates the amount of state funding used to support transit operations by a selection of California’s larger operators in 2019, the last full year before transit funding and operations were disrupted by the pandemic. The methodology (and requirements) for NTD reports differ (sometimes significantly) from the methodology some agencies use to categorize their budgets, and the numbers do not match up neatly. Regardless, the general trend of how much state support is used for operations is broadly consistent across both data sources and shows that state funding makes up only a relatively small portion of the operating funding that California's largest and most productive transit systems rely on, as shown in the table below. This is particularly true for the largest and most productive systems in the Bay Area, and for Metrolink, which receives no state funds from these sources.

California provides significant funding to transit, but state funds account for only a small portion of what the state’s largest and most productive systems spend on operations.

Use of State Funds to Support Operations, 2019

| Transit Agency | Agency Operating Budget

| State Funds Applied to Operating Budget

| NTD-Reported Operating Expenses

| NTD-Reported State Funding

| NTD-Reported Annual Ridership

|

| LA Metro | $1,775 million | $432 million (24%) | $2,021 million | $441 million (22%) | 380 million |

| SFMTA | $1,135 million | $106 million (9%) | $924 million | $166 million (17%) | 223 million |

| BART | $922 million | $38 million (4%) | $789 million | $40 million (5%) | 128 million |

| AC Transit | $443 million | $96 million (22%) | $477 million | $75 million (16%) | 54 million |

| Caltrain | $151 million | $3.7 million (2%) | $145 million | $4.3 million (3%) | 18 million |

| Metrolink | $241 million | $0 (0%) | $246 million | $0 (0%) | 13 million |

Conversely, analysis of 2019 NTD data for other large transit systems throughout the United States suggests that state funding often plays a more significant role in supporting transit operations for many big systems, particularly those serving large metropolitan areas on the East Coast.

State funding for large transit systems varies significantly throughout the United States but is constantly higher in large East Coast cities with mature and highly used transit systems.

Use of State Funds to Support Operations of Select Large Transit Agencies Outside California, 2019

| Transit Agency | NTD-Reported Operating Expenses

| NTD-Reported State Funding

| NTD-Reported Annual Ridership

|

| New York MTA | $13,108 million | $3,629 million (28%) | 3,792 million |

| CTA (Chicago) | $1,513 million | $320 million (21%) | 456 million |

| MBTA (Boston) | $1,866 million | $825 million (44%) | 367 million |

| SEPTA (Philadelphia) | $1,391 million | $696 million (50%) | 308 million |

| New Jersey Transit (Newark) | $2,358 million | $846 million (36%) | 267 million |

| King County Metro (Seattle) | $916 million | $20 million (2%) | 129 million |

The State Can Do More

California has made it clear that transit is central to its future, but for transit to realize its pivotal role, the state must help transit agencies recover and transition to a sustainable business model.

Remaking transit’s business model will take time, and multiple levels of government will ultimately need to work in coordination to help transit recoup and build ridership, identify new sources of funding, and bring costs and revenues into long-term alignment. Changing transit’s business model will also require structural reforms that can help focus transit’s mission and reduce costs without sacrificing service quality or the quality of jobs in transit operations. Much of this work is already underway at the agency and regional level, with efforts like the Transformation Action Plan in the Bay Area identifying a range of strategies to improve the customer experience and grow ridership. And while the state does not yet have a coherent policy or investment strategy for public transit, Assemblymember Laura Friedman’s AB 761, which sets up a statewide task force to address fundamental public transit challenges, is a big step in that direction.

But strategies to grow ridership and reform transit — even those currently being implemented — will realistically take years to reach a scale at which they will have a significant impact on agency financials. In the meantime, there simply would be no path to financial sustainability for transit, let alone growth, if California’s largest systems slipped into a death spiral of ever deeper service cuts and disrepair. Without high-quality service, we will tip further into the death spiral and lose more riders, and revenue. Bridge funding for operations is absolutely urgent and essential to the future of transit in the state. California’s leaders have a choice: influence the trajectory of transit for the better or stand by for transit’s demise.

Thank you to Jim Lightbody for providing research support.