Every year, SPUR takes a study trip to learn from other cities around the world. This spring we visited Detroit, a city that has long grappled with challenges the Bay Area now faces. We found much to admire in Detroit’s focus on community-based interventions and recovery. See the bottom of this page for more articles about the trip.

“Detroit is big enough to matter in the world and small enough for you to matter in it.”

— Jeanette Pierce, City Institute, Detroit

Detroit is a great American city that has required extraordinary resilience from its residents. It is simultaneously “Motor City,” where Henry Ford built his first car in the twilight of the 19th century, the birthplace of Motown, where the world first learned of Marvin Gaye, Diana Ross, and many others, and a city scarred by freeways, redlining, population decline, and high rates of poverty. It suffered deeply through the Great Recession, when 130,000 Detroit homes went through foreclosure. In 2013, the city went bankrupt and had to be financially restructured.

But Detroiters love their city. And it’s not hard to see why: beautiful historic buildings; a waterfront and park system that look out upon Canada; neighborhoods where people are deeply invested in their homes, communities, culture, and each other. Yet Detroit presents a series of challenges for its residents that the public sector, philanthropy, and others have yet to fully address — though not for lack of trying.

In 1950, Detroit was booming: the fourth largest city in the United States, just after New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia, had a thriving industrial base. But by the end of the 1960s, Detroit started losing population as factories left the city and white households moved to the suburbs. The shrinking has slowed over the last decade, but it hasn’t stopped (although Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan asserts that the current census undercounts Detroit’s population). Built for roughly 2 million residents, Detroit peaked at 1.85 million residents in 1950, and population has declined every decade since. The current population is roughly 620,000 residents, a drop of nearly 1.2 million residents since 1950.

As the population has declined, the share of Black households has increased, especially in the context of the larger metropolitan region. Almost 78% of Detroiters are Black, whereas 64% of the region is white. While Detroit’s population has dropped, the population of the region has stayed the same or grown.

Detroit’s population has declined from 1.85 million people to 625,000 people in the past seven decades.

Detroiters are poorer than their counterparts in the rest of the state. The median income in Detroit in 2017 was less than $28,000 annually, compared with more than $52,000 for the state as a whole. By way of contrast, the median income for the average-sized Bay Area household in 2020 was roughly $108,000.

The physical geography of Detroit is vast: the city covers almost 140 square miles. More than 70% of the housing stock is single-family homes. As people left the city, vacancy increased, and by 2012, 40 square miles — almost one-third of the land in the city — was left vacant. Landscape architect Azzurra Fox has described Detroit as “... a city of muscular flatness, an exuberant horizontal spread, marked now by the unlikely coexistence of Black cultural resilience and a pattern of land vacancy that rises as high as 75 percent in some areas.”

The city has struggled with the challenges of providing basic services and maintaining infrastructure across a large geography with a limited tax base. Everything from trash pickup to police and fire service to basic road repair has suffered. As the costs of services and an unfunded pension liability rose — and the tax base declined — the city’s finances collapsed. In 2013, Detroit went bankrupt. A significant restructuring took place, and with it a rethinking of city planning.

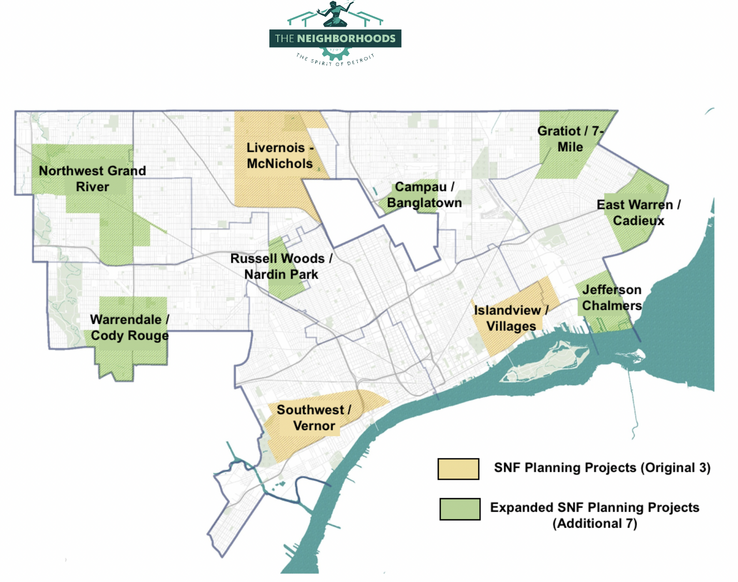

Philanthropic funds were critical to addressing the bankruptcy. Foundations provided $370 million to address Detroit’s unfunded pension liabilities, and philanthropy has played a vital role in supporting planning efforts to rebuild Detroit’s neighborhoods. More recently, philanthropic and city leaders decided to focus on Detroit’s neighborhoods, building on those with the most residents to reach as many people as possible. This effort, called the Strategic Neighborhood Fund, is coupled with a fund that finances infrastructure improvements, commercial and housing development including affordable housing, and investments to support businesses, largely Black-owned, along commercial corridors. Although results from this effort have been positive, many areas outside of the Strategic Neighborhoods remain in need of attention.

Pursuing neighborhood-based solutions makes sense, but it’s potentially insufficient to address the crisis of housing instability and inhabitability that the city is facing. Between 2005 and 2015, almost a third of Detroit’s residential properties — roughly 140,000 homes — experienced foreclosure. Some of these foreclosures were due to mortgage defaults, but many — close to 110,000 — were due to property tax delinquencies. Although a poverty property tax exemption exists, it is not well used, and owners need to apply annually to receive it. Property taxes in Detroit are extremely high, creating precarious situations for Detroit’s low-income homeowners.

Philanthropic efforts in the form of the Make It Home program have enabled some renters facing eviction due to foreclosure to become homeowners. Through this program, the City of Detroit purchases properties before foreclosure and then sells them to a nonprofit entity funded by philanthropic dollars from the Rocket Community Foundation. The nonprofit then works with residents to help them purchase the home. This program has been extremely successful, helping almost 1,400 families. Another city effort, the Pay As You Stay program, allows owners to stay in their homes as they pay off their property tax debt. These thoughtfully designed programs are bright spots in addressing Detroit’s foreclosure challenges.

Another challenge the city faces is that much of its housing stock is old and doesn’t meet basic habitability standards. Almost 90% of Detroit’s housing was built before the lead paint ban in 1978, creating a significant health risk for the city’s children.

Moreover, many Detroit homeowners are unable to get a mortgage loan or to refinance their property — the traditional route to finance home improvements — due to a variety of factors. First, the mortgage needed by the typical Detroit homeowner may be smaller than that a conventional mortgage lender provides. Second, the amount of funding needed may exceed the value of the property. And third, the typical Detroit homeowner may have challenges accessing credit thanks to decades of racist policymaking. In fact, many Black homeowners in Detroit rely on risky land contracts instead of traditional mortgages.

The city is committed to creating more affordable housing options for Detroiters. Last year Mayor Duggan announced a $203 million dollar plan, including funding to increase the habitability of existing housing. But the need for additional funding is substantial. Perhaps even more important is the need to address the factors that led to Detroit’s bankruptcy and that continue to keep many of its residents in an economically precarious place. They include the city’s high property tax rate and devastating tax foreclosure system and residents’ lack of access to sustainable and equitable mortgage lending. Institutional racism creates stark contrasts between the city and the surrounding region — contrasts with life-impacting consequences.

Detroit is a beautiful city with a big heart, and Detroiters deserve the opportunity to thrive.

Read more coverage of our Detroit trip:

Detroit’s Riverfront Transformation Offers Lessons for Revitalizing San José’s Guadalupe River Park

How Detroit’s Food Entrepreneurs Are Invigorating Commercial Corridors and Neighborhoods

The Role of Public-Private Partnerships in Downtown Detroit’s Revitalization