Read the complete strategy >>

Zoning regulations make it difficult to build new housing in many parts of the city. As the city has down-zoned existing residential neighborhoods to preserve their character, very little other land has been identified to fulfill the demand for new housing sites. To the address the issue of land availability and density, SPUR recommends that the City undertake the following four actions:

- Rezone underutilized land from industrial and commercial zoning to encourage moderate- and high-density housing.

- Increase heights and densities along neighborhood commercial corridors and major transit routes.

- Revise height and bulk limits in certain residentially zoned districts so that they are better synchronized with Building Code height restrictions and building envelopes that are feasible to construct.

- Allow Planned Unit Development approvals for residential and mixed-use developments on lots smaller than a half-acre.

Each of these recommendations can be implemented through amendments to the City’s zoning map and Planning Code. Those amendments will require action by the Planning Department and Commission, Board of Supervisors, and mayor.

1. Rezone underutilized land from industrial and commercial zoning to encourage moderate and high density housing. PARTIALLY UNDERWAY.

A large majority of the vacant and underused land in San Francisco is currently zoned for industrial uses with low height limits, making housing a disfavored land use. “Live/work” projects were the only residential uses permitted in these industrial lands, leading to a boom in the construction of lofts, but a shortage of land for more conventional housing construction.

The historically industrial areas of San Francisco should be re-examined to identify portions of those zones that can be changed to residential or mixed use zoning, with appropriate adjustments in height limits. The zoning designations for these areas date back to 1935, when San Francisco’s job base was largely industrial. The job base has changed over time, but the zoning has not, leaving hundreds of acres of land zoned exclusively for industrial uses that will never return. The types of “industry” that are attracted to San Francisco (technology, multimedia, printing, business services, possibly bioscience, etc.) are not the types of smoke-stack industries of the past that needed to be segregated from residential development. Rather, housing can co-exist with these newer, clean uses, which almost always require less land per job than older industries.

Intervention by the Redevelopment Agency may be necessary in some cases to create the types of infrastructure improvements necessary to support new residential neighborhoods. Muni service to many of these areas will need to be augmented. Parks, libraries, and other amenities will need to be planned for.

STATUS: Since the first publication of this report, the debate over the future of the city’s industrial areas has become a major controversy. Many planners and housing activists have agreed with SPUR’s position, and have focused their attention on the

industrial areas as the most important locations for building new mixed use neighborhoods. Other activists, including those who oppose market rate housing in general and those who believe industry needs to be protected from housing, have fought to create socalled “industrial protection zones.”

Out of this contest of ideas, in 2002 the Board of Supervisors initiated a major planning process to look at the future of the industrial neighborhoods on the eastern side of San Francisco. This “Eastern Neighborhoods Planning Process” was supposed to look at Showplace Square, the Bay View, Visitacion Valley, the Mission, and SOMA—an impossibly large area—with a tiny budget and no clear mandate other than to take account of “community” concerns.* So began the attempt by various interest groups to be viewed as the legitimate representatives of “the community.”

In late 2005, the Planning Department issued its "Proposed Zoning Controls for the Eastern Neighborhoods." This document proposes a comprimise between housing advocates and industrial-protection advocates. Whether the zoning controls proposed in this document are ultimately adopted remains to be seen. SPUR continues to make three major arguments about the future of the historically industrial lands:

- We have to find someplace to build housing. If the existing density of residential neighborhoods is only able to accommodate small, incremental infill development, then it makes sense to look at the historically industrial areas south of Market for a major piece of the housing solution. If we decide that preserving the industrial character is sacred, then we are choosing in essence to pull up the drawbridge and prevent anyone else from coming here—and we can predict what the character of such an exclusionary city will become.

- Every inner city in the country has experienced de-industrialization since World War II. There are many causes, but chief among them are the desire of companies to move to locations with cheaper labor costs and easy truck transportation. Zoning for industry will not bring it back.

- The types of industry that remain viable in a dense city like San Francisco—ranging from niche manufacturing that requires a highly educated workforce to services that support the city’s residential customer base—are by and large compatible with adjacent residential development. We have the opportunity to adopt an urban model that has worked for thousands of years, in which workplaces and homes occupy the same streets. There are exceptions to this rule, such as warehouses that load trucks all night and dance clubs that play music all night, so it’s true that there need to be some non-residential “loud” zones, but the space they require is far less than the land currently zoned for industry.

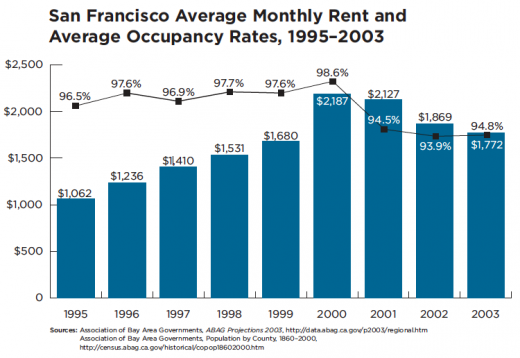

Percentages listed are average occupancy rates, dollar amounts are average monthly rents. Average rents in San Francisco went up 67% between 1995 and 2003. At their high in 2000, average rents were up 106% from five years earlier.

2. Increase heights and densities along neighborhood commercial corridors and major transit routes. PARTIALLY UNDERWAY.

There are numerous opportunities for the provision of higher density housing along moderately scaled neighborhood commercial corridors and major transportation routes, such as Geary Boulevard and Third Street. These streets already have or will soon have in place all the urban infrastructure needed to support relatively intense residential development (transit, retail, community facilities, etc.) and are distinct from surrounding low-density neighborhoods. San Francisco’s General Plan calls for such increased density along transit routes, but those policies have never

been translated into actual zoning.

With even a 10-foot increase in height limits in many neighborhood commercial districts (from the current 40 feet to 50 feet), significantly more residential units could be created with less expensive wood-frame construction methods, which allow four floors of residential construction above a retail and parking podium.

Existing retail areas should be studied individually to determine suitable locations for adding several floors of housing on top of commercial uses. These studies should

include determining appropriate locations for neighborhood shops, supermarkets, big box and shopping center-type retail, and institutional structures such as post offices and police stations.

Given the fact that most commercial areas are located on good transit routes, a reduction in parking requirements should be encouraged, particularly given the fact that commercial and residential parking can often be shared.

STATUS: The idea of focusing development along transit routes and neighborhood commercial streets is a recurring theme in this report. Probably the most important place this idea has been incorporated is in the Planning Department’s “Better Neighborhoods” program, an intensive neighborhood planning process now underway. So while no citywide rezoning of transit corridors is in the works, we are

making incremental progress on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood approach.

3. Revise height and bulk limits in certain residentially zoned districts so that they are better synchronized with Building Code height restrictions and building envelopes that are feasible to construct.

Currently, there is not a rational relationship between the height limits set forth in the zoning maps and Building Code height restrictions. Applicable height limits should be revised to better reflect Building Code standards.

For example, the current 80-foot height limits in some residential zones should be changed to 85 feet. The San Francisco Building Code allows buildings with a height to their top occupied floor of 75 feet or less to be designed with less expensive low-rise standards. As residential buildings typically have floor-to-floor heights of ten feet, an overall permitted building height of 85 feet (75 feet to the last occupied floor plus 10-foot story height) would be required to fully maximize the provisions allowed in the building code. An 85-foot height limit in lieu of 80 feet would permit one additional floor at maximum cost efficiency.

4. Allow Planned Unit Development approvals for residential and mixed use developments on lots smaller than a half-acre.

Currently, the Planning Code permits projects to be considered as planned unit developments (a more flexible site planning technique) by the Planning Commission only if the lot size is a half acre or larger and outside the downtown. The PUD process frequently permits more units with a better design, because the inflexible density, rear yard, setback, parking and other requirements of the Planning Code, that were designed for the typical 25- by 100-foot lot, can be relaxed. For example, PUDs enable the construction of courtyard housing. At the same time, a PUD must be approved as a conditional use by the Planning Commission, allowing the commission to regulate the overall design of each PUD and to require more of the units to be affordable through the “inclusionary housing” rules.

Given the small size of many developable lots in San Francisco, limiting the PUD process only to lots of a half acre or larger is neither necessary or desirable. The minimum threshold should be reduced to lots of 10,000 square feet or more.

Conclusion

Cities use zoning to ensure that new development enhances the community. When it’s done right, zoning can help ensure that new buildings are attractive, that they enhance the public realm (streets, sidewalks, plazas, parks), and that major trip generators are located near major transportation facilities.

But when it’s done wrong, zoning can be used as a device to prevent change and to keep newcomers from being able to move into the community at all. If the goal of “protecting existing character” is not balanced against other, equally important goals like reducing the jobs/housing imbalance, bringing down the cost of housing, and making the city a place that is welcoming to immigrants, then we will end up with a beautiful but sterile city of the wealthy.

Fortunately, many of the zoning changes that will allow the supply of housing to keep up with the demand will also make the city a better place to live: more walkable, more transit-accessible, more convenient for families with children, more socially diverse. Zoning for more housing is something that will make the city more livable and more affordable.

Several major facts jump out from this overview of the city’s housing stock. Two-thirds of the housing units are rental. About half of the housing units were built before World War II. Dwelling units tend to be small in size. Two thirds of the housing supply is in multifamily structures. All of these facts simply say that we are in an urban place, and that our housing development will continue to follow urban patterns. Source: Housing Element of the San Francisco General Plan, Draft July 14, 2003, p. 27; data drawn from 2000 US Census.

APPENDIX I: Housing Myths and Realities

Myth: The city is full. It can’t hold any more people without sacrificing our quality of life.

Reality: We can accommodate a great deal of population growth within the city limits in ways that actually enhance the quality of our environment, so long as we manage our growth sensitively. Most of the famous cities of Europe that are loved by Americans accommodate far higher densities than San Francisco. We can use new housing developments to enhance the pedestrian streetscape of our neighborhoods, to support more frequent transit service, to add neighborhood- serving retail, and to make our city more beautiful. If we close our gates to newcomers by a single-minded focus on preventing physical changes to the city, San Francisco will turn into a snobbish fortress of the elite. We can hold more people, we just have to plan to do it in the right way.

Myth: There’s nothing we can do about the housing problem—it’s beyond our control.

Reality: The city has been seemingly paralyzed to take steps to address the housing crisis, but there are many policy actions within our control on a local level that would make a difference. This report describes some of them. There is a lot we can do. The question is, will we have the political will to make the necessary

changes?

Myth: High prices in San Francisco result from greedy landlords and developers.

Reality: Landlords and developers are just as “greedy” anywhere else in the country. When housing is provided by the private market, the motivation is to produce a profit, just as with any other investment. Landlords and housing developers will charge as much money as they can. The difference is that, in places like San

Francisco, the constraints on housing production ensure that demand is not met, and therefore, people in the housing industry can charge higher prices. The

housing crisis has structural causes in our economy and government; it cannot be reduced to the psychological motivations of individuals.

Myth: Downtown luxury condominium construction is the problem. By attracting yuppies to the city, we are driving out true San Franciscans.

Reality: People are attracted to San Francisco because of the city, not because of ownership housing development. Failing to develop ownership housing only shifts the demand pressures onto other neighborhoods, thereby exacerbating gentrification and displacement. Unless we provide enough housing for the people who want to move here, those with greater economic resources will end up out-competing everyone else for the finite supply of housing.

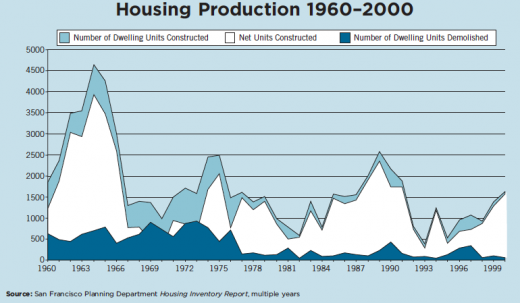

The amount of housing produced in San Francisco has varied widely over time. In general, periods with greater production, such as the late 1980s and early '90s, were times when rents and purchase prices were relatively constant.

Myth: Housing demand in San Francisco is infinite. Increasing supply will not bring prices down.

Reality: To say that demand is infinite is an exaggeration, which is fine as a rhetorical flourish, but misleading if it becomes the actual basis for public policy. This myth expresses the fatalism that so many people feel in the face of the housing crisis. It is a way of saying, “we will never be able to build the political will to bring down prices.” The reality gives us more reason to be hopeful. Between 1985 and 1989 approximately 9,400 housing units were constructed, including both rental and for-sale condominiums. This surge of supply was largely a result of numerous projects undertaken within Redevelopment Agency project areas that had been planned and entitled. With a slowing economy in the early 1990s, which reduced demand for housing somewhat, combined with the increase in supply, rental rates increased by less than the rate of inflation. Between 1990 and 1995, average rents increased by less than 10 percent, meaning an average of less than 2 percent annually, during this five-year period. Condominiums experienced average price declines of over 15 percent during this same five-year period. Between 2001 and the present time (2006), with another recession and another batch of new housing coming online, rental prices are again coming down. Housing in San Francisco does respond to supply and demand conditions, just as any other price system based on a large number of sellers and purchasers. The problem is that in the big picture, we have made it extremely difficult to add supply, so we are tens of thousands of units “behind.” Housing has become a “sellers’ market.” If we built enough housing, it would become a buyers’ and renters’ market.

APPENDIX II: What are the Components of Housing Price?

We can separate the components of the final price of a housing unit into three parts: construction costs, indirect or “soft” costs, and land price.

Construction costs include materials, labor, equipment, and contractor’s overhead and profit. The cost to build a unit of housing varies by construction type. Single family tract homes are the cheapest to build, followed by wood frame apartment buildings, followed by concrete and steel high rises.

But generally, construction costs do not explain the variation in housing costs between locations. Except for different site conditions and union vs. nonunion

labor considerations, construction costs are similar within the Bay Area, because materials, labor, and contractor’s profit are essentially the same across the region.

For a given building type, these costs will be similar no matter where one builds, and no matter who is going to live in the unit. Affordable housing does not cost less to build, it’s just that the price paid by the occupants is subsidized.

Indirect costs include everything else: architectural design, marketing, financing (interest) costs, legal fees, lobbying, construction insurance, government fees and permits, profits, etc. The housing approval process varies from place to place, which means that soft costs vary greatly by location. To understand why, it’s important to remember that developers typically don’t spend a lot of their own money, but instead get investors to put money into a project and borrow a portion of the construction cost from a bank. If a developer is successful, after paying all other costs and paying off the construction loan, he or she will pay back the equity to the investors together with a return on the investment. Developers compete for investment with all the other potential places that people can invest their money: the stock market, tech start-ups, and every other profit-making activity. Therefore, the cost to secure equity investors for housing projects is set by this competition between investment opportunities across the entire international economy.

Regulatory barriers to building housing and an unpredictable entitlement process add significantly to the indirect costs. First, developers in San Francisco have to spend a lot of money on lobbying and legal fees to get a project approved. Second, because the approval takes so long a large amount of money is spent on the carrying costs of land. And because the outcome is so uncertain, the perceived risks to investors are increased, which drives up the rate of return that investors demand. In addition, the up-front costs of developments which are never approved must be

recouped by those developments that are approved.

Land costs vary widely between locations. For example, land values in the South Beach neighborhood of San Francisco are much higher than in Oakland or Tracy.

Raw land prices are determined by how much revenue a piece of land would generate if it were developed at its most profitable use, subtracting the costs of development.

Rezoning a piece of land from single homes to apartment buildings usually increases the land price because it means that more housing units—and hence more revenue—can be earned from the same piece of land. On the other hand, demand for the uses that could theoretically go on a piece of land is much higher in some places than others. And the same house can be sold for much more money in a walkable, high amenity, desirable, urban area close to employment and street life than it could in a distant monocultural suburb.

Because a developer can sell the same housing units for more money in a walkable urban neighborhood of San Francisco and because there are many other valuable uses to which central city land can be put, land owners in those neighborhoods can charge developers extremely high prices when a developer buys a parcel. Thus, the cost of land is not what pushes housing prices in San Francisco so high. It’s the high demand for housing that pulls land prices up.

Policy Implications

1. Reducing parking reduces construction costs by about $25,000 to $50,000 per space. On the other hand, the loss of a parking space usually reduces the value of a housing unit by more than the construction cost savings. There are important exceptions: sites that can fit added housing units but not added parking spaces; market niches that do not need parking; and of course, specific population groups that don’t have high ownership rates. We do not yet know what the long-term impact of City CarShare will be on the value of parking spaces as part of a housing unit. Nor do we know how much people would be willing to pay for a parking space if the “externalized costs” of driving and car ownership were added onto the price paid by drivers. Reducing parking requirements is going to be hard to do in the short run, but it is important for the long term viability of the city and for our continued ability to add population into our small land area.

2. Developers factor in all costs when they decide how much to bid for a piece of land. As long as the zoning rules are predictable and known in advance, developers will simply do the math (revenues minus costs) to determine what they can pay for land. If the rules change in mid-stream, the investors in a project either make a windfall (if the rule change benefits them) or lose their money (if the change does not benefit them). For this reason, when the City changes zoning or adds a new fee, it is usually fair to have phase-in periods that grandfather in projects which have already applied for permits.

3. Fees and exactions are factored into land price like any other cost. As long as they are predictable and known in advance, they don’t come out of developer earnings or investor profits; they come out of the price of the land. However, if fees and exactions are too high, the costs of development can be so great that it makes more sense for land owners to hold their land than to sell it to a developer—meaning there is no possible development that would earn money once the fees and other costs are paid. When land values get driven below the current use of the land, such as single story retail or surface parking, then land owners will not sell to developers.

4. Anything we can do to make the approval process for new housing faster and more predictable will reduce “carrying costs,” an important component of soft costs. Carrying costs are the payments developers make to control a piece of land before they are allowed to start construction, and they can be many thousands of dollars a day. To take just one example, the carrying costs on a 100-unit project might be $5,400 each day. If the approval period could be shortened from 18 months to 6 months, the cost could be reduced by almost $20,000 per unit. Making the approval process for new housing more predictable and shortening the time line will reduce the carrying costs of a development and reduce the cost of borrowing money to build housing.