Restricting the Pie

In both San Francisco and California, voters have tied the hands of government officials in two key ways. First, through state Propositions 13 and 218, we are limited in our ability to secure new revenue to pay for government. Taxes and most charges on property owners require voter approval, often at the difficult-to-attain two-thirds majority. Second, through mandates that dedicate government spending, policymakers are restricted in their efforts to allocate public resources. This is because voters have predetermined how much of the budget will be spent — long before revenues are known. And so when there is a deficit, there are few places where the City can look to share the burden of cuts within the budget.

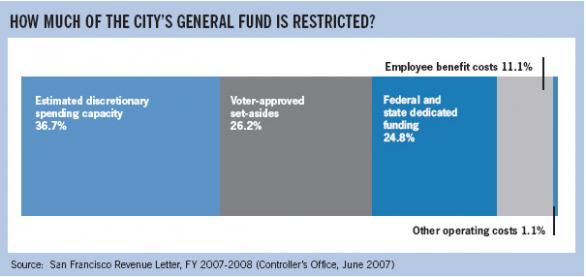

Of the $6.07 billion City budget for San Francisco in the 2007-2008 fiscal year, only $1.1 billion is discretionary, or available for the executive and legislative branches of government to decide how to spend. The remainder is restricted by federal, state and local employment provisions and a variety of mandated baselines and set-asides. Neither the mayor nor the Board of Supervisors can modify the vast majority of the budget.

Many of the dedicated spending requirements result from ballot measures. Every few years, voters have adopted new legal requirements to spend specific amounts of money for specific purposes. These requirements, commonly referred to as budget set-asides, range from formulas that allocate a specific fraction of the budget for a particular service (such as the library set-aside reauthorized in November 2007) to requirements that the City maintain minimum staffing or service levels (such as the 1994 requirement for minimum staffing at the Police Department).

The dedication of the budget by votes of the people has become increasingly common across California. In one sense, it is just another variant of the broader rise of the initiative, part of a long-term trend of supplanting representative democracy with direct democracy. Like other uses of the initiative process, set-asides are attractive to advocacy groups: They often find that initiatives enable them to frame issues and gain voter support more easily than they can persuade legislators to support their interests.

How Set-Asides Work in San Francisco

Despite the common idea that the City has a “$6 billion budget,” and thus that any expenditure of several million or even tens of millions appears small, the actual General Fund of the City is much smaller. The General Fund is the portion of the City budget that is “discretionary” — that is, it isn’t dedicated to any specific purpose, but is available for the mayor and the Board of Supervisors to distribute as they wish. Of the total $6.07 billion City budget, only about $1.1 billion — or 18 percent — is discretionary funding. The remainder includes set-asides or baseline funding, enterprise departments (departments that fund themselves through their own income) such as the airport and Water Department, worker and retiree benefits, interest payments, and federal and state funding. Much of the federal and state money the City receives, particularly in public health and social services, also is dedicated and restricted funding in that it requires the City to provide certain services in order to get access to the money.

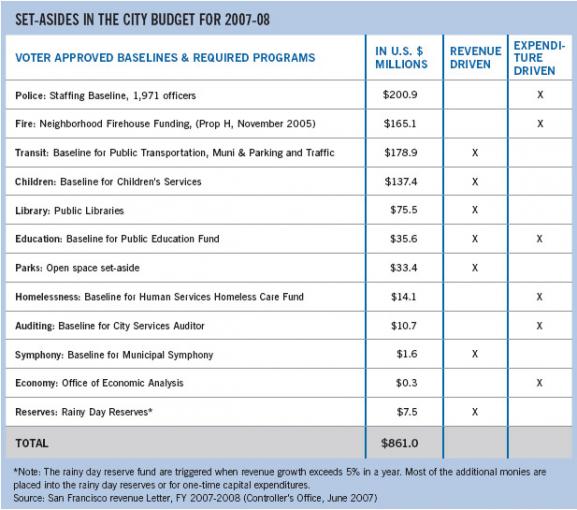

The total amount set aside in the City budget for dedicated spending and programs is about $860 million. The set-asides fall into several main categories. First there are revenue-driven and expenditure-driven set-asides. Revenue-driven set-asides rise and fall based on the total tax revenue coming to the City. For example, a set-aside that is a percentage of the general fund typically is revenue-driven. Expenditure-driven set-asides mandate a minimum amount of spending regardless of economic conditions and City tax revenue. These set-asides often are based on a percent of all property values.

In addition to the design of the set-aside, some measures include baseline funding. While functioning as a set-aside in restricting the City’s ability to reduce funding, a baseline is somewhat different in that it does not actually “set aside” a portion of either revenues or expenditures. Instead, it simply is a requirement to spend at least a certain amount on a service. Some measures that are primarily revenue-driven also have a baseline.

Set-asides in the City budget include minimum staffing requirements, dedicating a percent of all general fund revenues, restricting the use of particular revenue (like parking tax meters) for a specific service. In total, they account for approximately $860 million in expenditures this year.

SPUR’s History on Set-Asides

Historically, SPUR has been somewhat skeptical of set-asides. Part of this comes from our views of the ballot initiative process. We have argued that measures should not be on the ballot if they don’t have to be, unless progress through the normal lawmaking process is blocked. The initiative process can be far less protective of the interests of minority voting blocs: It enables groups that can muster 51 percent of the vote to get everything they want, rather than accept the give-and-take that comes with the legislative process. The initiative process discourages compromise, tradeoffs and the balancing of competing interests.

We also have never been convinced that the ballot initiative process really serves its original intended purpose of being a check on special interests controlling politicians. It has always appeared to us that the voters are just as subject as politicians are to manipulation by self-interested groups with money. Some of these issues are complex, yet people are casting votes with only the most casual idea of what the measures will do.

As a specific type of ballot initiative, set-asides have their own set of problems. We have argued that elected officials should be allowed to do their jobs and allocate resources according to the greatest needs, balancing out all of the competing demands on the finite amount of money available in any budget. We also recognize that service needs and delivery methods change over time, and that requiring a minimum amount to be spent on a particular service each year does not recognize the potential for innovations that increase the efficiency and lower the cost of service delivery. Finally, set-asides ask voters whether they want to spend a specified amount on a particular public service, but the voters are never provided the context to know if the figure specified is the right amount, or what the affects of the set-aside will be on other, unmentioned public services.

Yet, in spite of this skepticism about initiatives in general and set-asides in particular, SPUR has supported many ballot measures of both kinds. Partly, this is because there are actual advantages to set-asides and disadvantages to the legislative budgeting process, both of which we discuss later in this article. But more fundamentally, we often have been willing to let the substance of a measure — Is it a good idea? Will it work? Is the amount of money being dedicated for a given purpose appropriate? — trump our opposition to a bad process for enacting it.

Overall, SPUR has not been consistent in our position on set-asides. Over the past 15 years, we have proposed and drafted several set-asides (primarily for Muni), supported others (such as for open space) and opposed several more (such as for neighborhood firehouses). We have written this article as a statement of official SPUR policy because we want to offer a set of tools to help in drafting, evaluating and interpreting set-asides.

The overall goal, of course, is to enable government to work better so that it can continue to solve important problems and provide the public services we need. We believe that if set-asides are getting in the way of the core functioning of government, everyone should be willing to regard them with a critical eye and identify another way to ensure that valued public services receive sufficient funding.

The Case for Set-Asides

In the idealized model of public budgeting in a representative democracy, there is little need for direct citizen-imposed budgetary controls such as set-asides. Elected officials have access to information from professional public managers about the implications of budget decisions. These professional managers’ day-to-day exposure to the minutiae of government operations allows them a more refined understanding of individual budget decisions than most citizens, who are occupied with other matters and have limited time and limited desire to turn their attention to the vast majority of nuts-and-bolts decisions involved in an annual budget. Moreover, the budget is a primary tool for policymakers to develop and carry out a policy agenda. Without this tool, they cannot effectively carry out the will of the electorate or be fully held accountable by the electorate for outcomes while in office.

In practice, however, a number of intervening factors prevent this idealize model from becoming reality, and lead to public demands for budgetary controls such as set-asides.

Pro #1: Set-asides can offer an opportunity for citizens to express and enforce clear and nuanced policy goals.

Voters choose between candidates for office based on a set of expressed policy preferences on a wide range of issues. Since voters can only weigh in on the “whole package” of candidates rather than officeholders’ individual decisions, their ability to enforce policy outcomes on a specific issue can be limited. Set-asides give voters that opportunity.

Pro #2: Set-asides reduce the pressure to reallocate the budget annually.

In some cases, short-term political pressures often lead to budgetary decisions by elected officials that undermine important social goals and long-term fiscal responsibility. Elected officials have limited terms in office, and often face decisions that pit the short-term appeasement of particular political constituencies against longer-term outcomes that may not become apparent until the officials are no longer in office. Furthermore, political incentives make it less attractive for officials to save money than to spend as much as possible in any given year.

An example of a measure intended to counter these pressures and temptations is San Francisco’s Rainy Day Reserve, established by voters at the ballot through a charter amendment in 2003. In years of strong revenue growth, when they City coffers are flush, revenue growth more than 5 percent must be deposited into a Rainy Day account that can be accessed only in difficult economic times when revenues decline. While this measure limits the discretion of policymakers in budgeting, it is a common-sense savings requirement intended to help moderate the draconian cuts often called for during difficult economic times.

This kind of moderating mechanism, smoothing out the swings between budgetary highs and lows, is particularly valuable when spending priorities are represented by politically powerful interests or organizations that may give them an undue weight in the budget process, while other socially important goals may lack effective political representation, and as a result may be unable to compete effectively despite their importance.

For example, infrastructure needs often don’t compete well for funding against social programs whose beneficiaries literally can put a face to a budget item. Elected officials, perhaps unsurprisingly, often choose to push infrastructure to the back of the line, and the compounded costs to the public as a result of deferred maintenance seldom become apparent until those officials have retired from public service or have moved on to other offices. In such a situation, a set-aside could potentially provide both an assured source of funding and political cover for elected officials who may otherwise be inclined to shift funding elsewhere.

The City’s General Fund is approximately $2.9 billion, about 46% of the total budget. This is the source of

money for most basic services and the only portion of the budget that is discretionary. Set-asides alone

comprise more than 26% of the General Fund.

Pro #3: The “use it or lose it” system of public budgeting often limits the ability of managers to make the best use of resources.

This discourages efficiency and entrepreneurial behavior in public organizations. Some argue that this situation often can be corrected by set-asides or other budgetary controls. Agencies generally are allocated a specific amount of money at the beginning of a year. If an agency has savings at the end of the year, the people making budget decisions may perceive this fact as evidence that the agency received “too much” money in the budget, and reduce the agency’s budget in the following year. As a result, when the end of the year approaches, agencies may face an incentive to quickly spend whatever funds they have remaining so their budgets are not reduced in the following year, even if these expenditures are not top priorities. Similarly, agencies may fear being punished in the budget for cost-saving programs or efforts to fund reserves that they will be able to use to sustain operations in the future during difficult financial times.

A striking example of this was the change that occurred at Muni, as a result of the 1999 Proposition E (SPUR’s first Muni reform measure), which gave Muni a guaranteed funding baseline for the first time and made the Municipal Transportation Agency somewhat autonomous from the rest of City government. For many years prior to the set-aside in 1999, Mayors and Supervisors regularly reduced Muni funding. The result was a system with insufficient investment to maintain excellent service which then resulted in a self-feeding cycle of declining ridership and reduced revenues.

Following Prop. E, the MTA created a real-estate division to generate money from “air rights” development on top of bus yards and other facilities. Before Prop. E, any such development revenues would have gone to the General Fund; after Prop. E, the MTA got to keep them. One example since then is the Hotel Vitale at the foot of Mission Street, which earns the MTA an average lease payment of $4.8 million per year over the term of a 65-year lease (or over $300 million total) This example of entrepreneurial government was directly encouraged by new incentives from a set-aside in the budget.

Pro #4: Interest groups have disproportionate power in the annual budget process, and their influence may not reflect the will of the voters.

For example, the size of various city budgets without set-asides is in some ways a reflection of the underlying power of the employer groups in each department. In short, some public sector unions are stronger than others and thus more effective at capturing a larger share in the annual budget process. The alternative — establishing budget levels through voter-approved set-asides — is arguably a reflection of the will of the voters at a moment in time. While voters can be swayed easily by a well-financed campaign, they are at least the decision-makers instead of elected officials who often require funding for their next campaign from powerful actors such as businesses and labor unions.

Pro #5: Set-asides provide more stable funding to departments.

As a result of this phenomenon, some argue that agencies should have a more stable level of funding from year to year and be allowed to keep their savings, so they have a budgetary incentive to find efficiencies and engage in multi-year budget planning. Since most governments operate on a one-year budget cycle, the most obvious way to accomplish this goal is to create some form of budget set-aside to protect this type of entrepreneurial behavior against short-term political pressure. At the extreme, proponents of this view argue that the entire budget should be set-aside. In other words, the budget should be split up according to set percentages that reflect voters’ policy preferences, and these percentages should remain constant to maximize the ability of professional managers to make the most of the resources they receive.

The Case Against Set-Asides

Set-asides reduce discretion and choice, not just for government officials, but also for citizens. As economic, political and technological change occurs, set-asides lock in choices that may no longer make sense. In this way, they fundamentally damage the democratic system by devaluing and restricting the decisions of voters and legislators in future years.

Con #1: Set-asides are usually approved at the ballot box and presented to voters in a way that ignores necessary tradeoffs.

The budget process is about balancing among parks, libraries, Muni and a host of other services and, by definition, makes tradeoffs among competing — and often equally important — priorities. Instead of asking voters whether they prefer a certain level of funding for one service or program even if it means reduced funding for other purposes, set-aside measures often simply ask voters whether they support funding for a given program. With these tradeoffs invisible, voters naturally will be inclined to support funding for most programs. When these single-choice priorities accumulate over the years, as they have in San Francisco, we end up with a two-tier system consisting of the top tier that receives some special set-aside, while the second tier fights to a slow death for declining resources.

Con #2: The growth in the use of set-asides undermines representative democracy.

While there are many reasons to be frustrated with the standard budget system, the “solution” of set-asides actually worsens the problem by reducing choice and flexibility.

Proponents argue that set-asides take away the ability of politicians to reduce “important” programs during difficult times. This is exactly the problem. We should want decision makers to have the most complete range of choices possible during thin times in order to make the best possible choices. For example, San Francisco’s set-asides for parks and libraries may require inappropriate and unnecessary levels of funding during a time when all choices should be on the table. When faced with a budget deficit, it might be appropriate for the City to reduce funding for parks while maintaining or increasing funding for health.

Another common argument in favor of set-asides is that they give strength to political causes or uses that are less popular. This is, on its face, wrong: Only well represented public services or interest groups have the ability to win the votes necessary to create a set-aside in the first place.

Con #3: Set-aside amounts are disconnected from the need or demand for service.

For example, use of parking meters by car drivers does not reflect the demand for transit, which is funded by the parking meters. Fixing set-asides as a specific amount or baseline similarly disconnects need from support. For example, if children’s services receive funding as an increase each year from a baseline, that is disconnected from the actual number of children served and the level of service needed.

Con #4: Set-asides do not guarantee an improvement in quality of service.

The argument that an agency will be more entrepreneurial if it can expect a stable level of support over time does not always ring true. In fact, the vast majority of public budgets are stable, regardless of their perceived quality of service. Public budgeting is inherently a very incremental process, and therefore both stable and predictable. Most public budgeting processes use the prior year as a “baseline” for the following year. In other words, the starting point is the status quo, and changes during the budget process are incremental.

Con #5: Set-asides discourage savings and discretion.

Proponents of set-asides have raised the concern that departments that do not spend all of their budgets are “punished” by having their budgets reduced in subsequent years. It is true that this has been typical practice, especially at the level of the Board of Supervisors. In some cases, this approach is appropriate, since under-spending may indicate over-allocation of resources. However, there also are situations in which under-spending represents careful management of resources that can be rewarded by permitting the use of some of the savings for improvement of other important programs. It is important that discretion in the use of savings be preserved in the budget process.

While it is true that set-asides that receive new funding sources do not affect the existing “pie” of resources available for other purposes, the use of a new revenue source for a particular purpose still skews and limits future choices by failing to allow that new revenue source to be used for future needs that may not be well understood. Proponents argue that set-asides give “worthy” causes dependable and guaranteed funding. This is true, but they give this funding at the cost of damaging all other public purposes.

Yet, we already have a system that has set up numerous set-asides. Instead of decrying all set-asides for their failure to adhere to a strict definition of public budgeting, we at SPUR instead want to offer a way of understanding what kinds of set-asides may be more or less attractive.

Guidelines for Drafting and Evaluating Set-Asides

SPUR believes that set-asides are here to stay. While we recognize the challenges they cause, we also see the real limitations in the normal budgeting process, where powerful interests compete to secure their own share of discretionary spending.

The guidelines below are meant to assist future drafters of set-asides such as members of the Board of Supervisors or other proponents. They also are meant to help voters and organizations like SPUR in the evaluation and interpretation of the merits of individual set-asides. Ideally each measure would be used in drafting a set-aside measure. In some cases, it is not possible for a measure to meet all of the guidelines. Nevertheless, they should be viewed as something to strive for.

1. Set-asides should fluctuate with revenue.

Set-asides generally come in two forms: 1) a percentage of revenue coming into the City and 2) a minimum dollar figure (usually referred to as a “baseline”). The former is preferable. Advocates often desire baselines to ensure a minimum funding level for a given service. However, in years when revenues are in decline, baselines often are more damaging, as they take up a larger share of total revenues and thus impose greater limitations on policy-makers’ ability to fund other essential services because the remaining pool of funds available for appropriation is smaller. Set-asides should move up and down with overall City revenues. An example of a set-aside that meets this criterion is the Rainy Day Fund, which dedicates revenues only when there is revenue growth in excess of 5 percent. Set-asides that do not meet this criterion are the Open Space Fund, the Children’s Fund and the Library Preservation Fund, all of which take revenues as a percent of assessed property values.

2. Set-asides should be tied to a new revenue source.

Set-asides should be tied to a new revenue source so they do not reduce the pool of funding available for other existing services. Most local set-asides do not fit this criterion. The state set-asides for transportation, however, do meet it. They capture a portion of the gas tax and the fuel excise tax and dedicate it to transportation.

3. The revenue source should be closely related to the service funded through the set-aside.

If possible, the revenue source that funds the set-aside should have some relationship to the service if funds. For example, a Muni set-aside makes more sense when linked to parking tax and parking-meter revenues than when linked to real-estate transfer tax revenues, since there is a linkage between the use of parking spaces and traffic congestion, and the quality of public transportation. While quality transit service certainly boosts property values (just look at the impact of BART on downtown San Francisco), the transfer of property from one owner to another does not affect transit in the way congestion from cars does. Set-asides that are tied to the growth of the General Fund alone do not meet this criterion.

4. Set-asides should maximize flexibility over time.

Voter-approved budgetary controls often are “locked in” unless there is a subsequent vote of the electorate. Politically, it is more difficult to reverse a set-aside than to add one. As a result, set-asides can remain in place long after the conditions that prompted their creation are gone. Even worse, a poorly designed set-aside that does not work as intended will remain in effect until voters can be persuaded to rescind or amend it. Therefore, set-asides should include time limits or “sunset” clauses. Set-asides that do not contain such a “sunset” provision include those dedicated to police staffing, neighborhood firehouses and Muni funding.

5. Set-asides should be attached to clearly identifiable and measurable outcomes.

Before a set-aside is submitted to the voters, it should identify what the measure is trying to accomplish, instead of simply providing a funding stream with unclear goals. The set-aside should be tied to a specific, measurable performance standard or outcome. For example, the Library Preservation Fund requires that the City operate a Main Library and 27 branch libraries, and that these libraries remain open a minimum of 1,211 service hours per week systemwide. These outcomes are easy to measure. If the measure were written in such a way that the library system simply received a set-aside (such as a baseline or a guaranteed percent of revenue) without any outcome requirements, the public would not necessarily receive the same level of service, as the library would be able to invest its guaranteed funding as it saw fit. An example of a set-aside that does not meet this criterion is the one for neighborhood firehouses. That measure mandates means — that is, numbers of firehouses and types of equipment — as opposed to outcomes, such as improved response times or reduction in fire casualties.

6. Set-asides should be for a public purpose that tends not to compete well in the normal budgeting process.

Set-asides should be designed to fund a high-priority public service that cannot be funded or provided as well through other means. Some services or functions of government are regularly underfunded because the impacts of the investments accrue beyond the time horizon of most elected officials. For example, politicians often neglect infrastructure needs because the failure to address them does not typically yield positive dividends until after a politician has moved on. In such a case, the legitimacy of the public purpose of the set-aside is amplified by the political and budgetary context within which decisions about funding are made. We are not arguing for an infrastructure set-aside but offer this example as a contrast to other potential services which typically compete well in the budget marketplace.

Conclusion

The five recommended charter changes, combined with the seven evaluation criteria, would not end the practice of set-asides. Instead, they make slight changes to the practice of set-asides that will improve the overall budget process.

We remain concerned about the continued use of set-asides as a way to capture portions of the budget for particular services. Taken to the logical conclusion, everything in the budget could be mandated through set-aside, and we would cease to need legislators making tough choices. But some set-asides do make sense. The rub is deciding which ones.

We also recognize that the normal budgeting process often leads to deeply flawed outcomes as well. There will be times when set-asides are either necessary or acceptable. We hope that this paper can provide some ideas for good-government advocates and policy-makers about the pros and cons of the various budgeting approaches. We also wish to offer some guidance about how to design set-asides to minimize their negative impacts on the democratic process of representative government, and on the ability of our local government to function well. Finally, we hope that our proposed reforms will improve the overall quality of the public policy affecting set-asides.

Policy Recommendations

SPUR recommends that future drafters of set-aside measures use the above criteria when drafting their measures, and voters should use the guidelines when evaluating these measures. As an organization, in our review of ballot measures we will also apply these criteria when confronted with future set-aside ballot measures.

But we recognize that additional steps are required to yield the reform we need. Therefore, we propose several recommendations to improve the quality of existing and future set-asides. These recommendations require legislative action or reform of the San Francisco City Charter.

1. Require all new and existing set-aside measures to sunset.

SPUR proposes new charter language that requires all new and existing set-asides to expire after 10 years. This sunset clause would require that after 10 years, each set-aside is required to be evaluated and voted on by the Board of Supervisors. A super majority of nine supervisors could continue the set-aside for another five years. If nine supervisors do not vote to continue the set-aside, it sunsets and the department or service loses its dedicated status in the budget. If the set-aside receives majority support (that is, at least six votes), the Board of Supervisors can choose to place the set-aside onto the ballot, where it would automatically go back to the voters for approval. This is how the system works today for all set-asides with a sunset provision. This proposal would have avoided the November 2007 Library Preservation Fund campaign because that measure received support from 10 of the 11 members of the Board of Supervisors. Furthermore, unlike today’s rules, this proposal would not permit the set-aside from being renewed prior to the election closest to the year when it sunsets.

2. Modify set-asides to allow for limited amenability.

We propose new charter language for an amenability clause that permits the mayor or Board of Supervisors to alter the design of specific provisions without going back to a vote of the people. Under this recommendation, we would allow for a super-majority of eight members of the Board of Supervisors to make important modifications to the set-aside, such as the required uses of the funds within a department. For example, the neighborhood firehouse measure specifies the type of firefighting equipment to be used by the department. Such language has no place in the charter. This proposal would allow a super-majority of nine members of the Board of Supervisors to amend that clause.

3. Require controller’s statement on cost of set-aside when on the ballot.

SPUR proposes establishing a new charter requirement for a Controller’s Office statement when a set-aside goes on the ballot. The statement would provide the net present value of the measure as well as an analysis of the estimated fiscal impact on other services in the budget process. Set-aside measures today do not require any specific analysis of tradeoffs. Hence, voters are asked to approve set-asides based only on the value or merit of the service (such as schools or parks).

4. Require controller’s analysis of outcomes every five years.

SPUR proposes establishing a new charter requirement for an evaluation of outcomes by the City Services Auditor in the Controller’s Office every five years. The report would describe the specific goals and outcome measurements of the set-aside and would determine how the relevent departments have done in meeting those goals. If applicable, this evaluation would compare how the department or service performed prior to the passage of the set-aside.

5. Provide a clause for the suspension of set-asides in a qualified fiscal emergency.

SPUR proposes a new charter provision to allow for suspension of all set-asides in a qualified fiscal emergency. We would define “qualified fiscal emergency” as either a projected deficit of eight percent of the General Fund (as identified by the Controller’s Office revenue projections) or if the mayor, the controller and a majority of the Board of Supervisors jointly declare the state of emergency. In such a situation, the mayor could suspend the set-asides, and all departments with set-asides would go back to zero-based budgeting. Unlike requirements at the state level, this measure would not require the City to reimburse the departments for the revenue they would have received if there had not been a fiscal emergency.