Photo by Sergio Ruiz

Photo by Sergio Ruiz

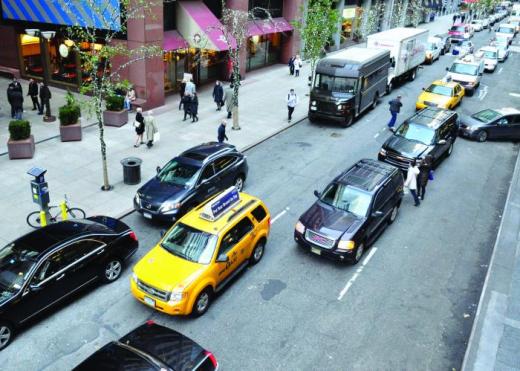

In the past six years, New York City has embarked upon the most comprehensive reconfiguration of city streets in the nation, rolling back generations of single-minded emphasis on vehicular traffic and pursuing a vision of streets that balance a wide range of functions, including travel by foot and bicycle as well as transit, taxis and cars. This program — in our nation’s most populous and prominent city — represents a profound shift in philosophy by America’s transportation planners and engineers.

This didn’t happen by accident. In cities from coast to coast, including San Francisco, “complete streets” (as multimodal streets are often called) has become a mantra. Getting them built, however, remains a frustrating and piecemeal process, which raises the question, how did New York get so much done so quickly?

Before this bike path was installed at Prospect Park, radar-gun studies showed that more than three out of every four motorists exceeded the 30 mph speed limit. One of three travel lanes were removed and a two-way protected bicycle path along the park was added.

The city officials whom SPUR met while visiting New York this past April repeatedly cited Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration as a key ingredient in their recent policy achievements. New York’s “strong system” — in which public agencies work directly for the mayor — is compounded in this case by a strong individual who is famously ambitious, results-oriented, data-driven and nonpartisan.

The scale and capacity of New York’s city government is remarkable. It delivers services to 8 million inhabitants, plus many more workers and visitors, and manages some of the world’s most significant public assets — from transit to parks to housing and public health. The city’s Department of Transportation (DOT), was primed for this effort, with ambitious staff and internal technical capacities that would be the envy of most major consultancies.

One of Bloomberg’s early initiatives was PlaNYC, a 2007 strategic plan for the city that emphasized sustainability as a way to absorb the million additional residents projected for the city over 25 years. If the city were to grow as much as predicted, it would, as a practical matter, have to move away from the private car.

The transportation component of PlaNYC included a controversial congestion-pricing scheme as its centerpiece, with multimodal transportation planning as another key element. When congestion pricing was killed at the state level, remaking the streets became the centerpiece.

To implement the streets vision, Bloomberg tapped Janette Sadik-Kahn for transportation commissioner and pledged to back her through the minefield of conventional transportation practices and politics. Sadik-Kahn took the vision to heart and her work has had remarkable impact.

In Brooklyn, this under-utilized slice of asphalt where Pearl Street meets Water Street, was transformed into a welcoming plaza with little more than seating, paint and plants.

In Brooklyn, this under-utilized slice of asphalt where Pearl Street meets Water Street, was transformed into a welcoming plaza with little more than seating, paint and plants.

Sadik-Kahn saw the job as a challenge of both technical innovation and public communication, and she bet that in a city where the pedestrian is king, more humane streets would be an instant hit — if she could get them built. Then the emphasis could be on seeing things on the ground, not talking about them in the abstract.

She used DOT’s ability to modify streets’ “operational” elements (like signals and paint) as a way to begin experimenting with temporary, reversible interventions. The DOT blocked off excess asphalt, added umbrellas, cheap chairs and color, and watched space-hungry New Yorkers feast on the new amenities. For a walking city, as Sadik-Kahn often pointed out, New York had almost nowhere to sit — a legacy of its late-20th-century rash of crime and homelessness.

The DOT began shifting auto lanes to other uses, gradually developing a pattern book of effective solutions. SelectBus (bus rapid transit) service was a natural for transit-rich New York, but embracing the bicycle was a bigger shift. Today, miles of physically separated cycle tracks — the first of their type in the country — run outside the parking lanes on major avenues. Hundreds of new plaza spaces allow citizens to sit and watch the world go by. Projects have been taken up opportunistically, with small interventions taming streets throughout the city. In many cases, initial designs have revealed flaws that were corrected in subsequent phases.

Throughout the effort, the DOT has held hundreds of public meetings, often generating design ideas and local insights into traffic patterns. Although there has been a degree of controversy, the efforts remain overwhelmingly popular. And though public process is important, it tends not to be viewed as an end in itself or a major quagmire. As one DOT staffer put it, “We don’t let the process become an excuse for inaction.”

Completed in 2012, these new crosswalks at 6-1/2 Avenue made a much-used shortcut a lot safer. The high-visibility crosswalks let pedestrians walk between 51st and 57th Streets mid-block without walking all the way to Sixth or Seventh Avenues.

While in New York, as elsewhere, the far right has raised the specter of a “war on cars,” the city has been careful to seek the optimum balance among different modes for the benefit of the system as a whole.

In many cases, apportioning differently can actually improve traffic flow, by reducing conflicts between cars and buses or converting travel lanes to turn lanes that remove queuing cars from the mix. And streets that allow movement by other modes during periods of congestion create a more resilient system overall.

DOT officials are explicit about seeking win-win or win-tie solutions and avoiding win-lose scenarios, which they view as detrimental to both their ability to maintain public support and the functioning of the system.

Planners of a certain generation have to pinch themselves when they see these ideas having such a transformative impact. Not long ago, these notions were dismissed as impractical flights of eco-topian fantasy. Today, accommodating transit, bicycles and even public life on our streets is professional orthodoxy. In San Francisco, we are only just learning how to bring those ideas to fruition. New York City is getting it done.