When U.S. troops were sent to the Mexican border in advance of the caravan of Central American refugees in November of 2018, it was only one in a series of executive orders and policy changes to militarize the border, tighten restrictions on asylum seekers, reduce the number of international students, reduce high-skilled immigration and generally make immigrants feel unwelcome. Other examples, from a long list, include:

• The travel ban on a set of Muslim-majority countries, first issued as an executive order in January 2017, was challenged in courts across the country last year and revised several times before being upheld in June by a 5 to 4 vote at the U.S. Supreme Court.

• The Trump administration announced the termination of temporary protective status for immigrants fleeing violence or other national emergencies in their home countries, including El Salvador, Haiti and Honduras.

• In April, the Justice Department announced a zero tolerance policy for unauthorized border crossings, which meant separating about 3,000 children from their families with no plan to reunite them. The administration described the policy as a strategy for “deterrence.”

• The State Department announced plans to restrict student visas and also plans to reduce the length of time that high-skilled immigrants on H1B visas can remain in the country.

• Republicans introduced legislation that would halve the number of legal immigrants allowed each year.

Many countries are experiencing their own version of an anti-immigrant backlash, but it is the United States whose national identity for hundreds of years has been to serve as a haven for people fleeing oppression or seeking opportunity, that is experiencing the strongest and strangest. As this issue went to print, the federal government was still shutdown as Trump continued to insist on funding for the building of a border wall.

Why is this happening now? Several reasons have been suggested: a reaction against the first black president; a cry of despair from the white working class in industries hit hard by everything from Chinese imports to automation; fear of Islamic terrorism that draws on 9/11 and the rise of the Islamic State, just to name a few. Many observers have noted that anti-immigration attitudes tend to be stronger in the places that have the smallest immigrant populations.

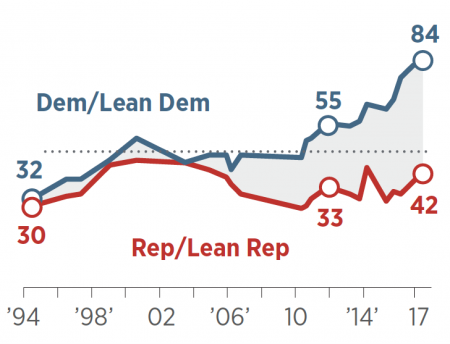

Immigration has become one of the biggest divides between Republicans and Democrats.

Share of voters who believe “immigrants strengthen America with their hard work and talents,” by political party

The debate over immigration will profoundly affect the fate of urban America. Our nation’s ability to absorb and assimilate so many people from so many different places — what most of us have believed is an essential purpose of our country — has depended on cities, which have always served as points of entry for immigrants. Cities have acted as containers for human diversity, encouraging everyone to more or less get along, in spite of differences in culture and language. The chaotic dynamism of the polyglot city is intrinsic to city life.

The U.S. has long been a country of immigrants.

Share of U.S. population from 1850-2016

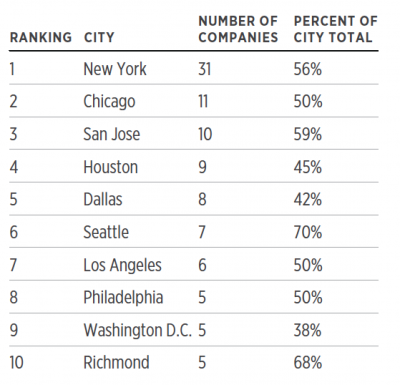

Places like the Bay Area (along with Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Seattle and so many others) have thrived in the modern economy by being able to attract highly educated, highly skilled people from around the world. The “brain drain” from the rest of the world has produced powerful engines of economic growth in the United States. Today, 43 percent of Fortune 500 companies have a firs tor second-generation immigrant as their founder. If the federal government restricts highly skilled people from moving to U.S. cities or closes the national borders, it will be a dagger through the heart of our social and economic model.

Immigrants make enormous contributions to America’s economic dynamism.

Share of immigrant- and immigrant-offspring- founded Fortune 500 companies by U.S. metro region

As the divide between Red America and Blue America seems to grow wider, perhaps nothing is more divisive than people’s attitudes toward immigration. For the past two years, as part of a broad attempt to reinvent a progressive form of federalism, blue states have tried to establish their own direction on issues from climate change to gun control for the past two years. Leading urbanists like Richard Florida and Bruce Katz have called for a “new localism” as a way to reduce the conflict, allowing states and cities to go their own way wherever possible. But it’s hard to imagine how this approach could work on an issue like immigration. No one is seriously proposing that states be allowed to set their own immigration policies, in part because of the practical impossibility of setting up internal border controls between states. So it appears that immigration policy is one of those areas where Red America and Blue America will continue to fight at the federal level. The outcome of that battle will determine whether our cities will continue their historic role as the places that hold diversity in all of its forms and turn people from all over the world into Americans.