Increases the city’s transfer tax rate on properties valued at $5 million or more.

What the Measure Would Do

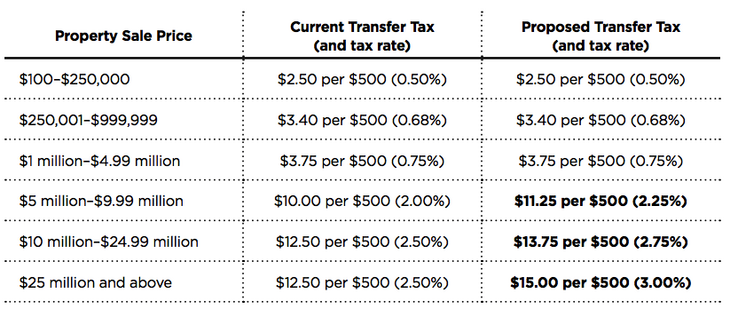

Proposition W would increase San Francisco’s property transfer tax rate from 2 percent to 2.25 percent on properties with a value of $5 million to $9.99 million and from 2.5 percent to 2.75 percent on properties with a value of $10 million to $24.99 million. The measure would create a new bracket for properties with a value of at least $25 million, establishing a transfer tax rate of 3 percent for those properties. Prop. W would make explicit that San Francisco’s transfer tax also applies to the sale of real estate owned by a partnership, such as a trust or a tenancy-in-common ownership arrangement.

Current Transfer Tax and Proposed Changes*

Source: Prop. W transfer tax legal text, SPUR analysis

The California Constitution limits the amount of local government spending on tax-funded public services each year, unless changed by a vote of the local electorate. This measure would increase the city’s annual appropriations limit for four years, to allow the city to spend the revenue collected by the transfer tax rate increase.

The City Controller’s Office anticipates that the rate increase would generate $44 million in additional annual revenue.1 The majority of revenue from this increase would be derived from large properties, most of which are downtown office buildings.2

The transfer tax is a general tax, and revenue from the rate increase would go into the city’s General Fund. In July, the Board of Supervisors passed a resolution of intent to make City College tuition-free for San Francisco residents and identified revenue from this proposed transfer tax increase as a possible source of funding. The subsidy for City College tuition is expected to cost the city $13 million for the first year, beginning in fall 2017.3 The Board of Supervisors has also expressed its intent to use a portion of the revenue from this tax increase to fund the $19 million Prop. E set-aside for street tree maintenance, should the voters approve that measure.4

The Backstory

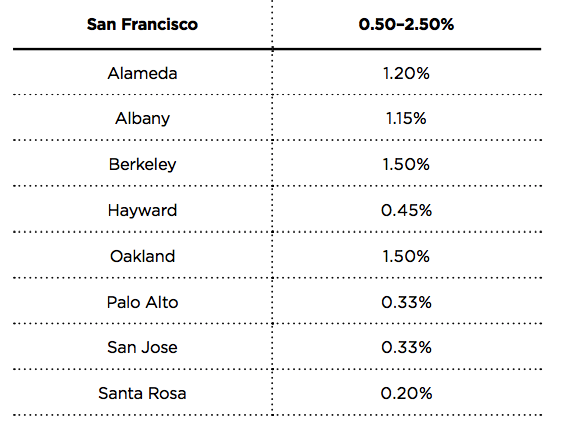

San Francisco charges a transfer tax on each commercial and residential property sold within city boundaries, equal to a percentage of the property’s sale price. The tax rate ranges from 0.5 percent to 2.5 percent and is typically paid by the seller. While other California cities charge a flat transfer tax rate, only San Francisco has a graduated rate, whose upper range (and, in some cases, lower limit) exceeds that of other cities in the Bay Area.

Regional Transfer Tax Comparison (Fiscal Year 2014-15)

Transfer tax revenue is highly cyclical, and more volatile than any of the other tax revenue streams that support the city’s General Fund; revenues fluctuate depending on the strength of the economy and the number of real estate transactions. Between the 2007–08 and 2009–10 fiscal years, transfer tax revenue declined by 66 percent. It has grown 133 percent since the recession’s end in fiscal year 2011–12.

San Francisco voters have twice increased the transfer tax over the last 10 years. In 2008, voters approved a proposition that increased the tax rate to 1.5 percent for transactions of $5 million or more. Revenues from the transfer tax had grown rapidly in the preceding years because of the overall growth in real estate values. But the impact of the recession and the bursting of the housing bubble resulted in a reduction in property values, transfer tax revenues and general city revenues. In 2010, voters approved another ballot measure to increase the transfer tax rate to 2 percent for transactions of $5 million to $9.99 million and to 2.5 percent for transactions of $10 million and above.

An important part of the context of this measure is the national movement to make community college tuition-free. The concept is supported by the Obama administration and gained additional prominance from the Bernie Sanders campaign. Many states and localities have instituted programs to provide free community college in the last year.5 Local proponents have identified the transfer tax as a possible source of revenue to fund such a program in San Francisco for residents and city workers.

Prop. W was placed on the ballot by a 10 to 1 vote of the Board of Supervisors. As a tax ordinance, it must be on the ballot and requires a simple majority (50 percent plus one vote) to pass.

Pros

-

Transfer taxes can be an appropriate place to raise revenue for public purposes because they extract a portion of a property’s increase in value at the point of sale and don’t directly disincentivize economic activity such as job creation.6 Transfer taxes are also an appropriate way for the city to recoup some investment because the value of property is tied to public assets like transportation improvements and public parks.

-

Revenue from this measure could go toward worthy programs — such as providing access to free community college education at City College — that may depend on the city creating a new funding source.

Cons

- While this measure is a general tax, the Board of Supervisors has declared intentions to use the funding generated by Prop. W for City College and for the Prop. E street tree program. It could be dangerous to dedicate transfer tax revenue, which is highly volatile and unpredictable, to programs that need steady funding.