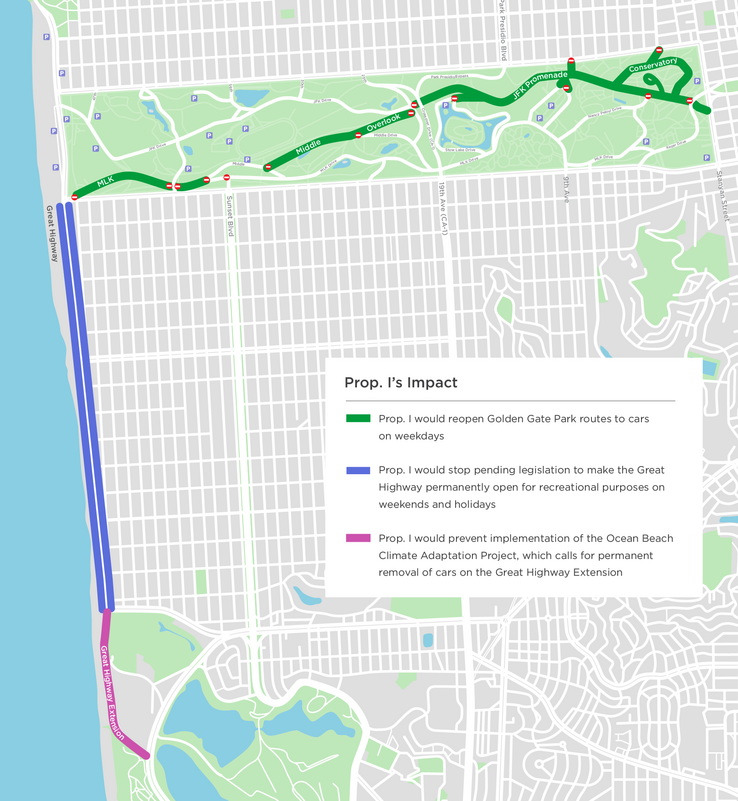

Eliminates the protected recreational space along JFK Promenade in Golden Gate Park by allowing cars on weekdays, prevents the city from keeping the Great Highway along Ocean Beach open for recreational purposes on weekends and holidays by allowing cars at all times, and prevents the city from moving forward with its sea-level rise adaptation plans on the Great Highway extension by preventing future road closure.

What the Measure Would Do

Along Ocean Beach, Proposition I would prevent the city from keeping the Upper Great Highway between Lincoln Way and Sloat Boulevard open for recreational purposes on weekends and holidays by requiring the City of San Francisco to allow private cars in both directions at all times.

Prop. I would also prevent the city from moving forward with its approved plans to close the Great Highway Extension to cars between Sloat and Skyline boulevards to implement a nature-based project to adapt to sea-level rise and protect the surrounding neighborhood and nearby sewage treatment plant from flooding.

In Golden Gate Park, Prop. I would eliminate the protected open space created along and around John F. Kennedy (JFK) Promenade. The measure would require the city to allow private cars to use JFK Promenade at all times, except on Saturdays from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. between April and September and all day on Sundays and holidays.

Prop. I would also require San Francisco Public Works (Public Works) to take over management of the Upper Great Highway from the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department (Rec Park).

Prop. I Would Impact Three Locations in San Francisco

The Backstory

Along Ocean Beach, the Great Highway was created and designated under San Francisco park jurisdiction in the 1870s as a space for recreation, with the current design being built in the 1980s.[1] In the late 1990s, the coastal area south of Sloat Boulevard began experiencing chronic climate-induced erosion, which threatened the Great Highway and wastewater infrastructure at an oceanside sewage treatment plant managed by the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC). SFPUC and other agencies actively participated in an inter-agency effort led by SPUR to develop a sustainable long-term vision for Ocean Beach.[2] The two-year effort also included an outreach program with stakeholder interviews, public workshops and multiple online resources.[3] The resulting Ocean Beach Master Plan, completed in 2012, outlined a number of key steps for a sea-level rise strategy that includes a limited area of "managed retreat" (the removal of roads or structures in the path of the advancing coastline) along the Great Highway Extension.

The master plan includes strategic recommendations for the removal of the Great Highway between Sloat and Skyline boulevards and the introduction of a multipurpose coastal protection/restoration/access system — all strategies that informed the development of the city’s Ocean Beach Climate Adaptation Project.[4] The project was co-developed among a number of agencies (Rec Park, SFPUC, the National Park Service, San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency and Public Works) and included contributions from community groups including the San Francisco Bicycle Coalition, San Francisco Parks Alliance, Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, Great Streets Collaborative and many more. The adaptation project’s proposed improvements to the area include adding a new multi-use trail for pedestrian and bike access. The project has been in design since 2020, and SFPUC has submitted a comprehensive plan for permitting review and approval from the California Coastal Commission. Construction is expected to begin in 2023.

The Upper Great Highway requires regular coastal sand maintenance and removal. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the road was added to the city’s Slow Streets initiative as a space for temporary recreational use. In August 2021, the Upper Great Highway reopened to vehicular traffic on weekdays. San Francisco Supervisor Gordon Mar submitted legislation to be considered in late 2022 that would require the city to maintain the Upper Great Highway as a recreational promenade on Friday afternoons, weekends and holidays under a three-year pilot study.

In Golden Gate Park, JFK Drive (now known as JFK Promenade) between Kezar Drive and Transverse was made available for recreational use without private cars on Sundays and holidays starting in 1967. In April 2007, the city extended recreational use of JFK Drive to include Saturdays between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m. from April to September each year.

In response to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the City of San Francisco established car-free routes throughout the city, including in Golden Gate Park, in an effort to create safer spaces for people to socially distance and recreate. This change became immensely popular. The protected open spaces, which included JFK Drive, created a virtually continuous open space route from one end of the park to the other. Close to 7 million visits have been made to the JFK portion of the open space route since the change, which is 36% more daily park visits than before.[5]

Supporters of the expanded recreational open space in the park organized and advocated to make the pandemic-era response permanent. Of 10,000 respondents surveyed, about 70% said they wanted the routes to stay car-free.[6] In April 2022, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved legislation in a 7–4 vote to convert JFK Drive to the JFK Promenade open space and included amendments requiring city officials to provide two years of quarterly reports about progress in improving parking options and access for disabled people. Known as the Golden Gate Park Access and Safety Program, this decision greenlit more than 40 improvements to make the park easier to access for seniors, disabled people and other residents. Prop. I would end this program.

Those supporting Prop. I claim that allowing cars to traverse the park on a greater number of routes reduces traffic in surrounding neighborhoods. However, traffic analyses done by the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) found no significant impact to travel times contributing to traffic congestion in north-south and east-west trips since the route’s conversion to open space.[7]

Supporters of Prop. I, such as the de Young Museum, also maintain that the creation of the JFK Promenade open space has made it difficult to access the museum and led to a marked decline in museum attendance (48% lower than the same period before the pandemic). However, adjacent cultural institutions in the park, such as the California Academy of Sciences and Japanese Tea Garden, have reported that attendance is almost back to pre-COVID levels, and the San Francisco Botanical Garden, also in the park, has surpassed previous visitor levels in the last two years.

A simple majority (50% plus one vote) is needed to pass the measure; however, it is in direct conflict with Prop. J, also on the November ballot. If both measures pass but Prop. I gets more votes, then Prop. I would prevail in its entirety and would nullify Prop. J. However, if both measures pass but Prop. J gets more votes, then the entirety of Prop. I would be null and void. Read our analysis of Prop. J.

How Does Proposition I Relate to Propositions J and N?

In support of preserving JFK Promenade, Supervisors Rafael Mandelman, Myrna Melgar, Matt Dorsey and Hillary Ronen put Prop. J on the November 2022 ballot. Prop. J would amend the Park Code to reauthorize the Golden Gate Park Access and Safety Program, preserve recreational and open space use of JFK Promenade and connecting streets, establish bicycle lanes and implement public access improvements to Golden Gate Park. Prop. J is a conflicting measure to Prop. I. In the event that Prop. J passes with a greater number of votes, the result will be to nullify the entirety of Prop. I, even the parts of the measure that apply to the Great Highway.

Additionally, Mayor London Breed filed Prop. N, which would allow the city to acquire, operate and subsidize public parking in the Golden Gate Park Concourse Underground Parking Facility. The measure would transfer jurisdiction of the facility to Rec Park and effectively dissolve the Golden Gate Park Concourse Authority. Voter support for this measure would potentially make the 800 parking spaces below the museums more accessible after the city is given jurisdiction to set rates or subsidize them. The parking garage has existing elevators that carry passengers directly to the museums. Prop. N is not in conflict with either Prop. J or Prop. I. Read our analysis of Prop. N.

Equity Impacts

Proponents of Prop. I equate car access to the Great Highway and JFK Drive with access for all. But evidence shows that before the pandemic, 75% of the vehicles on JFK Drive neither started nor stopped in the park, indicating that they were using the park road as a thoroughfare, not for park access.[8] The measure proposes no improvements to the park or highway to expand accessibility options for seniors, disabled people or others. On the other hand, the April 2022 legislation that created the JFK Promenade open space, which this measure aims to reverse, includes significant improvements to ADA infrastructure, shuttle service and more.

Although the opening of JFK Promenade resulted in 1,000 fewer parking spaces, the park will continue to have 5,000 remaining surface parking spaces and expanded blue-zone parking spaces for people with disabilities near the museums and the botanical garden.[9]

Along the Great Highway, the Ocean Beach Master Plan outlined a number of key steps for a managed nature-based retreat strategy in response to sea-level rise and erosion. By not pursuing a nature-based adaptation strategy, the city would be required to build a large sea wall along the beach to protect the surrounding neighborhood and sewage treatment plant from flooding. This would mean that the Outer Sunset neighborhood and amenities such as Fort Funston, the Zoo and more would be subject to the construction and consequences of a sea wall. Researchers from the United Nations have concluded that while seawalls protect coastal properties and beaches, they are expensive, damage wildlife, mainly benefit the rich and encourage risky building near the coast.[10] This approach would inequitably concentrate city resources on a maladaptive long-term strategy.

Moreover, if Prop. I passes with a majority of votes, the city would be required to embark on a legally murky process to enact its provisions. SFPUC has made significant progress in planning and implementing the Ocean Beach Climate Change Adaptation Project, a process that began with the co-developed Ocean Beach Master Plan outreach and policy project in 2010. The Ocean Beach Master Plan to adapt to sea level rise and erosion was adopted through a public process by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and the Coastal Commission as part of the Western Shoreline Area Plan (part of the city’s General Plan).[11] It is likely that overriding these policies, as the measure proposes, would require additional amendments and may spark lengthy litigation. This measure would effectively derail years of prolonged community engagement, city planning and policymaking in favor of an unknown and indeterminate course of action to implement Prop. I’s provisions.

Pros

- SPUR could not identify any pros to this measure. For what proponents say about Prop. I see The Backstory.

Cons

- Prop. I would repeal legislation that was passed by the Board of Supervisors and developed through a multi-year public process that incorporated significant data analysis and public input, especially from those most impacted by the projects.

- This measure was developed without any public input.

- The measure would eliminate the JFK Promenade open space, which was the most used open space in the city over the past three years.[12]

- This measure would prevent the city from protecting the Outer Sunset neighborhood and a sewage treatment plant from flooding as a result of sea-level rise.

- Reopening car-oriented highways and arterials through the heart of the city would increase air pollution and climate emissions and would create more traffic, making public transit slower and less reliable.