The Metropolitan Transportation Commission (MTC) is in the process of developing Clipper 2.0, the next generation of the Bay Area’s Clipper transit fare payment system, with anticipated release in the early 2020s. This is the first in a series of blog posts looking at how Clipper 2.0 can be designed and developed to help Bay Area cities meet their transportation, equity and sustainability challenges.

There is no denying that the Clipper card is a magical piece of plastic. Since its debut in 2010, Clipper has made it much easier for people to switch between different transit systems and travel throughout the region. But if you look under Clipper’s hood, it quickly becomes apparent that the card’s magic masks a complex web of transit fares, passes and policies that ultimately limit its effectiveness. Put simply, a close look reveals that the Bay Area has a fare policy problem.

What Is Fare Policy?

“Fare policy” refers to the rules defining how much people pay to use public transit. There are four main components that transit operators consider when setting fares:

- Fare structure – How will the price of a ride be set: by distance, zones or a single flat fare? Will riders receive discounts when transferring to a different system, such as from BART to a bus? Are there different prices at different times of day? Will riders be charged extra for special service, such as taking an express bus?

- Price – What will a full-fare single ride cost?

- Payment options – How will riders pay: single-ride tickets or daily, weekly or monthly passes?

- Discount categories – Which riders, such as youth, seniors and people with disabilities, will qualify for a discounted fare, and how much will those discounts be?

Fare policy is a powerful tool because it impacts all aspects of the transit system: the number of people who ride, boarding times, operating costs, customer satisfaction and affordability for people with low incomes. Yet, for transit operators, the need to recover a certain portion of operating costs from fares tends to be the overriding objective. For this reason, fares policies often change in response to a particular issue or problem — notably a budget shortfall — rather than being updated based on policy and business goals.

Where Bay Area Fare Policies Are Going Wrong

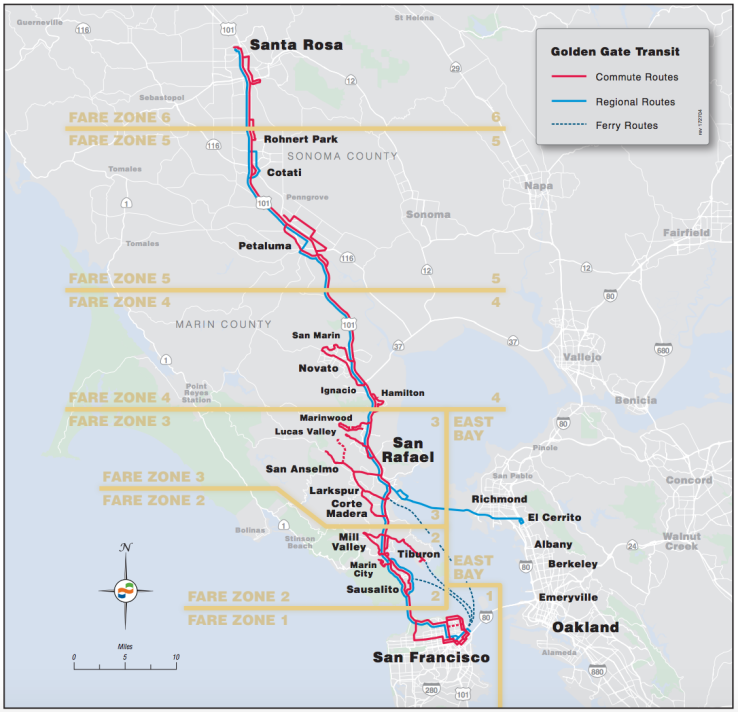

There are 27 different transit operators in the Bay Area and each sets its own fare policy, resulting in a hodgepodge of different fare structures, products, discounts and prices across the region. For example: while the majority of operators have flat fares (the fare is constant regardless of time of day, distance or type of service), BART uses distance-based pricing (the fare is based on how far a rider travels), and Caltrain, Golden Gate Transit and SMART use zone-based pricing (fares vary according to the number of zones crossed, see map below). Most Bay Area transit agencies provide fare discounts to seniors, youth and people with disabilities, but the discounts vary by operator, as do the definitions of who qualifies for the discount.

Golden Gate Transit Uses a Zone-Based Fare Structure

The price of a ride on Golden Gate Transit varies by the number of zones crossed. Image courtesy Golden Gate Transit.

The price of a ride on Golden Gate Transit varies by the number of zones crossed. Image courtesy Golden Gate Transit.Some coordination of fares does exist, but it’s limited in scope and has been developed on an ad hoc basis. The most common way that Bay Area transit operators coordinate fares is by offering a discount on transfers. For example, several bus operators offer a discount when transferring to their service from BART. There are no regional passes — passes that allow riders to travel on some or all transit services in a region for a specified period of time — although some sub-regional passes do exist. For example, the Muni + BART pass provides unlimited rides on all Muni service and on travel between BART stations within San Francisco.

The original development of the Clipper card did not involve a concentrated effort to rationalize the Bay Area’s highly disjointed fare landscape. According to SPUR interviews, transit operators were not required to change fare policies or products when MTC launched TransLink, the predecessor to Clipper. As a result, transit agencies merely replicated existing fare products in digital form on Clipper. (See SPUR report Seamless Transit, p. 22.) While Clipper has removed a barrier to traveling on multiple transit operators, it did so only by masking this complexity, leaving a host of problems that make it challenging for the region to realize the promise of transit.

Problem 1. Disparate fare policies make using transit confusing, hindering ridership growth.

Transit in the Bay Area is not for the faint of heart. Transit riders have to contend with an array of different fares and passes, not to mention, uncoordinated schedules, maps and wayfinding systems. Disparate fare policies can make navigating the transit system inefficient, cumbersome and costly, leaving riders feeling confused and discouraged.

Recognizing this, some transit agencies in the Bay Area and beyond are actively working to reduce complexity and make fares across operators more uniform. Santa Rosa City Bus, Petaluma Transit and Sonoma County Transit, for example, are coordinating their next fare change so that they will all charge the same price for a single trip. Portland recently adopted its first transit card, the Hop FastPass, which is valid across the region’s three operators. Like Clipper, the card stores “e-cash,” but unlike Clipper (which supports more than two dozen different passes) the Hop FastPass offers only a daily and a monthly cap, and they work across all three operators. Once a rider spends the value of a daily or a monthly pass, he or she won’t have to pay any more that day or month. There’s no wading through a stack of pass options; riders automatically receive the savings once they reach the cap.

Research shows that strategic changes to fare policy that eliminate confusion and provide seamless travel can help grow ridership. Transport for London (TFL), which operates the London Underground, saw a 3 to 5 percent boost in ridership when, like Portland, it started offering riders the option to “pay as you go” across five different modes of transportation. TFL found riders appreciated that the fare was designed to give them the best value, and this feeling of trust translated to more rides and revenue for the agency.

Fare Structures and Products Differ Across Bay Area Transit Operators

Problem 2. If there’s congestion or a service disruption, today’s fare policies will not come to the rescue.

Fare policy isn’t designed to lend a hand when there’s congestion or a disruption in one system. Existing fare passes establish loyalty to transit operators and not to a regional transit system. If something happens on their usual transit service, riders may be unlikely to try switching to another operator because it has a different and unfamiliar set of practices, prices and products. Furthermore, riders may not have the right “currency” to use a different service. Products that mimic e-cash, such as BART’s High Value Discount (HVD) ticket, are particularly problematic in that they provide the sense of having currency that can be used on any transit system but are in fact specific to one operator. In case of an emergency, riders can’t use their BART HVD fare balance to take the ferry or a Transbay bus — and this is often news to them.

Problem 3. Today’s fare policies make it difficult to offer transit passes that match how people actually use — or could use — transit.

A growing number of employers, transit management associations and cities want to encourage transit use, and several Bay Area institutions and organizations have mandates to do so. But fare policy makes it difficult for them to do the right thing. Over one-third of Bay Area employees cross a county line to get to work. Yet transit passes are operator specific and serve the location where the business is based, not necessarily where its employees live. For Google to meet the transit needs of its employees when it move s to the Diridon Station Area, for example, it would need to buy Caltrain GoPasses, VTA EcoPasses and individual passes for other agencies in order to get its employees to work on transit. It wouldn’t make financial sense for Google to buy employees one of each, not to mention the logistical challenges of coordinating with both employees and individual agencies to purchase the appropriate number and type of passes.

Seattle, like the Bay Area, has multiple transit operators, but unlike the Bay Area, its employers have the option to purchase a multi-agency transit pass for their employees — and many do. Nearly 2,000 business participate in the program; ORCA Business Passport sales accounted for 47 percent of all fare sales in 2016, and 65 percent of transit boardings in the county are made by someone with an employer-subsidized fare card.

By not having pass products that match how people travel, we may be depressing the number of transit trips people choose to take. Research shows that transit passes subsidized by third parties such as universities and large employers generate more profitable trips per passenger for transit operators. And it’s not just about commute trips. Riders may use one transit system to run errands, another to visit friends and still another to get work. A rider using a pass pays no cost for each additional trip, which promotes the use of the transit system for all different types of trips.

Problem 4. Our fare policies penalize riders who take multi-operator trips.

The lack of fare coordination among connecting transit agencies means that riders who need to transfer between operators often must pay two or more different fares. The way the system is designed discourages riders from transferring to another operator, even with transfer discounts. Some transit trips require one regional operator and at least one local operator. The distance of the local leg may be negligible, but transit riders still pay nearly the full local fare to travel that first or last mile. The part of the trip that’s the shortest in length often ends up being the most costly. This can discourage riders from taking transit. Indeed, the Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area found that having riders pay again if transferring between the bus, subway and regional rail discourages transit trips, reduces the market for cross-boundary trips and causes people to make inconvenient travel choices.

Singapore tackled its own “double fare barrier” by designing a fare structure where riders are charged based on the distance traveled, regardless of how many different modes are used to complete the journey. Sydney addressed the same issue by offering riders a $2 discount when they transfer from one mode another.

Problem 5. Existing fare policies price some people out of transit.

Residents with lower incomes are being displaced from the Bay Area’s core to outlying areas, where they are farther from jobs and schools. MTC’s recent Means-Based Fare Study found that many riders with low incomes need to use more than one ride, and in many cases more than one transit system, to reach their destinations. But having to pay two or more different fares can put such a trip — and the access to opportunity it provides — out of reach. Low-income residents surveyed for the study expressed a desire for a regional pass that would reduce the high cost of multi-fare trips, but this solution is not possible within the parameters of existing fare policies as current policy does not support region-wide, multi-agency passes that make it easy for riders to take multi-operator trips.

What We Can Do: The Clipper 2.0 Opportunity

It doesn’t have to be this way. While each transit operator sets its own fare policy, transit in the Bay Area will work best when all the pieces fit together. No single municipality or transit agency can solve this problem alone. They will all need to work together to harmonize fare structures and develop regional passes that work on multiple systems, in multiple cities, and make it attractive to use transit for all types of trips, not just commute trips. Integrating and simplifying fares will not be easy. It will require investment at the regional level from individual operators, cities and employers, as well as riders. It will also require detailed policy changes, agency by agency and city by city.

MTC explored regional fare coordination nearly a decade ago, but the study was hamstrung by the requirement that solutions not negatively impact the revenues operators earn from fares —a condition that is mathematically nearly impossible to meet. As a result, nothing came of it. (Other regions, including Seattle and Zurich, that have streamlined multi-agency fares have addressed this by setting aside funding to compensate operators for losses and reward them for participating in a regional fare structure.)

The Clipper 2.0 process presents a tremendous opportunity for the region to address and correct the current system’s limitations. Conceiving and designing all the pieces of the new system provides the optimal time to rethink and reimagine fare policy — which is the building block of Clipper, after all. Yet much of the conversation around how to improve Clipper has focused on payment technology, rather than fare policies, even though fare policy has as much to do with improving the usability and appeal of Clipper as the technological fixes. The challenges with today’s fare policy landscape all ultimately land in the same place: your Clipper card.

The promise of Clipper was that it would enable riders to hop between Bay Area buses, trains and ferries without pause. But today's fare policies introduce friction into the experience, effectively undermining Clipper’s main selling point. Today, Clipper works best for commuters, higher-income earners and people willing to wade into the complexity, when it should work for people of all income levels, for all types of trips. We can’t make Clipper a more attractive, usable product — one that truly encourages the seamless use of multiple operators and helps to grow transit’s market share — without addressing fare policies.

As it stands, current fare policies will be replicated in Clipper 2.0. But why transfer all this complexity to the next iteration of Clipper when it makes the system more expensive to run and makes Clipper less customer-friendly? Other regions show that it’s possible to streamline and simplify fares and create cross-agency fare products before transitioning to new systems. Industry experts recommend taking this approach, noting that system delivery is faster and more reliable if fares are streamlined first.

The problems that the current fare policy landscape imposes can be greatly reduced — and potentially eliminated — if fare policies look beyond agency lines. In our next blog post we’ll look at some options for how the Bay Area can leverage technology to address its fare policy problem.