The rise of remote work and other economic changes have exposed the vulnerabilities of San Francisco’s existing business tax structure. The Office of the Controller and the Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector have studied potential tax reform recommendations that could serve as the basis of a potential November 2024 ballot measure. Their final tax reform proposal aims to increase the city’s economic resilience, create more transparency for taxpayers, and help struggling small businesses.

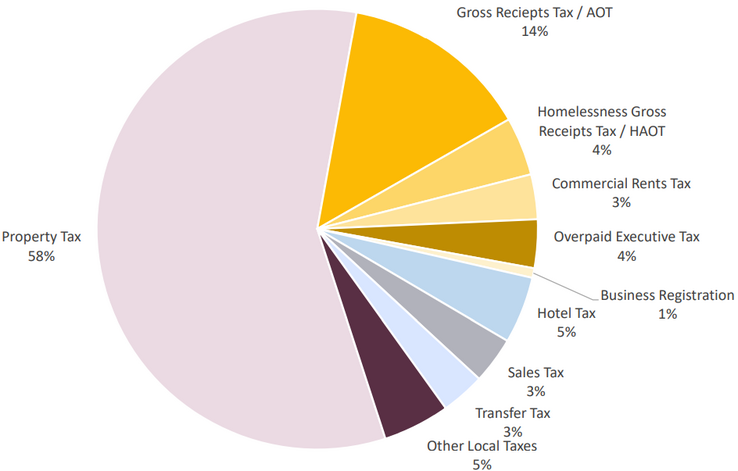

San Francisco collects about $1.4 billion per year in business taxes. Business taxes are the second-highest revenue source for the city, exceeded only by property taxes.

City Tax Revenue by Tax, Fiscal Year 2022–23 (Total: $5.8 Billion)

In 2012, San Francisco underwent major business tax reform when voters approved the city’s transition away from the payroll tax to a gross receipts tax. The change was prompted in part by the Great Recession. The flat payroll tax fluctuated with economic cycles, and it disincentivized hiring because the tax increased as businesses grew their payroll. In contrast, gross receipts taxes are generally more stable and predictable over time. As a progressive tax, the gross receipts tax rate increases on the basis of gross revenues, like the income tax, making it more beneficial for small businesses than a flat payroll tax.

In the last six years, voters have approved additional gross receipts taxes in addition to the base gross receipts tax, including the homelessness tax, the commercial rents tax, and the overpaid executive tax, which have almost doubled business tax revenues for the city. They have also concentrated the risk to the city by taxing office industries like tech and professional services at much higher levels than other types of industries.

Why is San Francisco considering business tax reform?

Many factors drive a city’s economic prosperity, including the labor force, land and buildings costs, amenities, infrastructure, local regulations, and taxes. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the rise of remote work, San Francisco has experienced rapid economic changes that have exposed some of the vulnerabilities of the existing business tax structure, as outlined in a 2022 report by the controller and the treasurer commissioned by Supervisor Rafael Mandelman.

Local taxes are one of the levers that city government can use to make the city more competitive and economically resilient. In 2023, Mayor London Breed and Board of Supervisors President Aaron Peskin requested that the controller and the treasurer study potential tax reform recommendations that could serve as the basis of a potential November 2024 ballot measure. The recommendations would address four structural problems.

Problem 1: Over the last decade, San Francisco has become more reliant on a small number of companies for its tax base.

In 2022, the largest five taxpayer firms paid 24% of all of the city’s business taxes. By comparison, in 2012, when the city had a flat payroll tax instead of a gross receipts tax, the five largest companies paid 7% of the city’s total business taxes. If any of these top employers were to leave the city, San Francisco’s fiscal health could be heavily impacted.

Problem 2: Remote work has weakened the city’s economy and created new risks to the city’s tax revenues.

For many industries, the city calculates the business tax owed on the basis of how many workers are employed in San Francisco. Under this “payroll apportionment factor,” the is tax is reduced if the employer has people on their payroll who are now working remotely outside of the city. With remote work, the number of workers in the office has shrunk considerably, especially in tech and financial services. As a consequence, the city is collecting lower revenues from those firms, which make up a high share of the city’s overall gross receipts. Remote work has also lowered the value of commercial office buildings in San Francisco, reducing the amount of commercial rents tax, property tax, and real estate transfer tax revenues that the city can collect.

Problem 3: Over the years, voters have passed numerous ballot measures that have increased taxes and created a volatile and complex business environment for businesses.

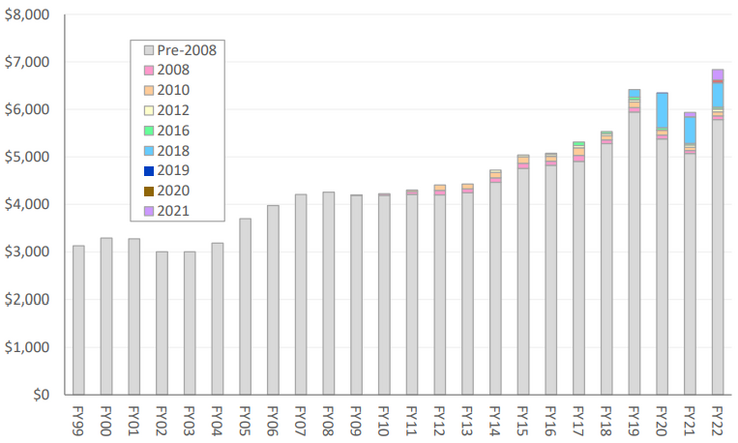

Compared with other cities in California, San Francisco has a low barrier to introduce new business taxes. Either a minority of the board of supervisors or the mayor alone can place tax measures on the ballot. San Francisco also has a lower signature threshold for voter initiatives to place tax measures on the ballot. Since 2008, voters have passed seven ballot measures to reform and to increase business taxes. The homelessness gross receipts tax, which passed in 2018, is the most significant of these measures, imposing an additional gross receipts tax on companies with revenues of greater than $50 million. The commercial rents tax, which also passed in 2018, is an additional gross receipts tax on income from commercial leases, primarily offices. The overpaid executive tax, passed in 2020, imposes an additional tax on the annual gross revenues of companies that have a high compensation ratio between top executives and the median San Francisco worker. In addition to becoming the highest-tax jurisdiction in the Bay Area, San Francisco now has very complex business tax structure with more than 14 categories and tiers. The combination of higher costs and uncertainty about future increases may have led some companies to leave the city.

Per Capita, Inflation-Adjusted San Francisco Tax Revenue by Year of Tax Approval

Problem 4: Many small businesses are struggling to survive and do not receive the business tax exemption.

Small businesses in San Francisco face multiple challenges: a notoriously complex regulatory environment, rising costs, and a slow economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The challenges are even more acute for small businesses in downtown San Francisco. Although the city’s progressive business tax structure exempts 85% of businesses with gross receipts no greater than $2.19 million, many small businesses, including restaurants, fall above this threshold. In addition, the city’s registration and licensing fees disproportionately burden small businesses, especially restaurants and bars.

What is the tax reform proposal?

The Office of the Controller and the Office of the Treasurer and Tax Collector released a report in February 2024 outlining their recommendations. Subsequent to outreach and engagement with businesses, they finalized their recommendations in May 2024. Their tax reform proposal would reduce the overall business tax revenues collected by the city but would increase economic resilience by reducing the city’s reliance on revenues from a small number of companies. It also would reduce the impacts of remote work and relocations on the city’s fiscal base, streamline calculations and collections, and cut taxes and fees for small businesses. The proposal’s key elements:

- Reduce the city’s vulnerability to remote work by changing the apportionment ratio. Taxes would be calculated on the basis of gross receipts in San Francisco and less weighted on the basis of their payroll in San Francisco. This important change would remove the disincentive for companies to have an in-person presence in San Francisco.

- Simplify the tax structure. The city would reduce the number of tax schedules from 14 to 7 to make it easier for businesses to understand their costs and for the city to administer the tax.

- Reduce the overpaid executive tax and rationalize the homelessness gross receipts tax with the gross receipts tax. The overpaid executive tax would be reduced by 80%. The homelessness gross receipts tax would have new tax schedules, rates, and tiers to make it more consistent with the gross receipts tax and to distribute the tax burden on a wider range of industries.

- Increase the small business tax exemption to businesses with gross receipts of $5 million. Consequently, almost all restaurants in the city would be exempt. The proposal would eliminate $10 million in licensing and registration fees that are a burden to small businesses, especially restaurants and bars.

- Increase the voter threshold to place new tax measures on the ballot to reduce volatility and uncertainty for taxpayers. The proposal recommends a charter amendment to increase the thresholds for placing business tax measures on the ballot.

What’s next?

Business groups, nonprofits, and labor organizations have joined the effort to collect signatures to implement the tax reform ballot measure in November 2024. The measure incorporates four of the five final recommendations from the controller and treasurer, leaving out amendments to the voter thresholds (element No. 5), which would require a charter amendment. If it qualifies for the ballot and is approved by voters, the proposed tax reform ordinance would become effective on January 2025.