Bay Area residents are keenly aware of the threat of sea level rise as the planet warms — but most of us know far less about the impacts of groundwater rise. In the Bay Area, those impacts will be felt long before sea level rise causes overland flooding. That’s one of the takeaways of a new SPUR case study that examines how one Bay Area community, East Palo Alto, would likely be affected in the absence of adaptation efforts. A complex history of racial segregation, economic inequity, and aging infrastructure — paired with exposure to hazards such as sea level rise, riverine flooding, extreme heat, and earthquakes — make East Palo Alto an important case study for exploring groundwater rise risks and working with community leaders to identify equitable coping strategies.

SPUR Hazard Resilience Senior Policy Manager Sarah Atkinson worked in partnership with community-based organization Nuestra Casa to identify the groundwater rise risks in East Palo Alto and develop recommendations to address them. Nuestra Casa serves the safety-net needs of immigrant and low-income populations in East Palo Alto and the mid-peninsula through community education, leadership development, and advocacy. The collaboration resulted in Look Out Below: Groundwater Rise Impacts on East Palo Alto — A case study for equitable adaptation.

We spoke with Sarah about the peril of not addressing groundwater rise, the specific impacts that East Palo Alto may experience, and the importance of partnering with community organizations like Nuestra Casa.

What is groundwater rise, and what’s driving attention to this issue now?

Shallow groundwater is fresh water that is stored in soils below the ground surface. As sea levels rise in response to climate change, salty San Francisco Bay and Pacific Ocean water can move further inland, pushing the groundwater up through the soil. This is groundwater rise. The closer the groundwater table is to the ground’s surface, the more likely that heavy rains will cause flooding of roads and buildings. But flooding isn’t the only concern. Groundwater rise is likely to corrode and disrupt belowground infrastructure, increase pollution entering the San Francisco Bay through stormwater outfalls, mobilize soil contaminants at hazardous material sites along the Bayshore, and increase the risk of liquefaction, where the soil acts like a liquid during earthquakes.

The recent emphasis on groundwater rise has been driven by local researchers from Pathways Climate Institute and San Francisco Estuary Institute and by Dr. Kristina Hill from UC Berkeley, among others. They have been raising concern about risks to low-lying communities on the San Francisco Bay shore, and their research inspired and informed this report.

When Nuestra Casa learned about groundwater rise, the organization wanted to understand what that phenomenon meant for the East Palo Alto residents it serves. SPUR had an existing partnership with Nuestra Casa and was also interested in groundwater rise, so we decided to investigate.

East Palo Alto is located adjacent to Bay marshland, so it’s particularly vulnerable to compound flooding from sea level rise, storm surges, extreme precipitation, and overflows at San Francisquito Creek. In the January 2023 storms, San Francisquito Creek overflowed at various locations, and some roads flooded due to stormwater system backups. Groundwater rise will only worsen these existing flood issues.

For East Palo Alto, what are the risks posed by groundwater rise?

First, groundwater rise will increase inland flood potential, especially in the eastern neighborhoods.

Second, groundwater rise will damage local infrastructure, particularly belowground water infrastructure. As shallow groundwater becomes more saline, sanitary sewer, stormwater, and drinking water pipes may corrode more quickly. In addition, a higher groundwater table will increase groundwater infiltration into storm and sewer pipes. East Palo Alto, like many cities, has aging underground infrastructure in need of both repairs and expansion to increase functional capacity. The city has three tap water providers, two of which are very small, serving about 3,000 residents each. Small systems, especially small systems serving disadvantaged communities, tend to have difficulty maintaining the technical, managerial, and financial capacity needed to safely operate a drinking water system. The city also recently opted to incorporate the East Palo Alto Sanitary District, previously an independent special district, because it was creating barriers to advancing new housing developments. Ultimately, groundwater rise will exacerbate the existing challenges in water infrastructure management in East Palo Alto.

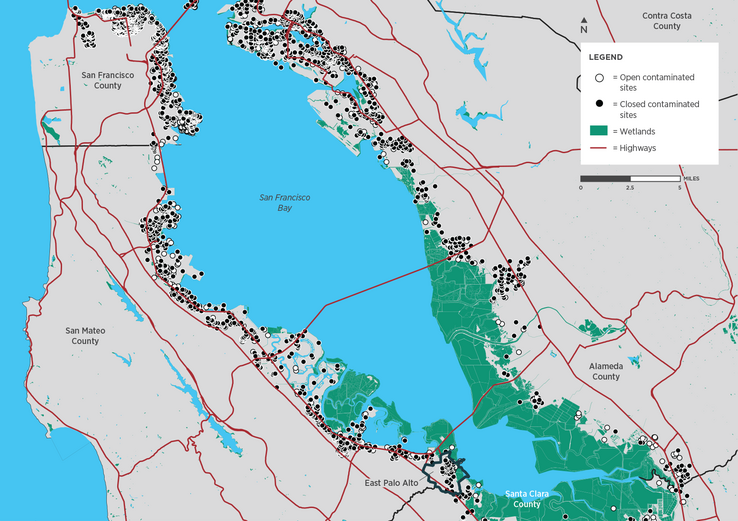

Third, groundwater rise will mobilize health-harming contaminants at legacy industrial sites, causing them to potentially travel into cracked storm and sanitary sewer pipes and to enter nearby homes. East Palo Alto has about 50 industrial sites vulnerable to groundwater rise. The former site of Romic Environmental Technologies, now owned by Bay Road Holdings, is at the center of environmental justice efforts. More research in needed to understand pathways for contaminant mobilization by groundwater and the resulting public health impacts, but it’s clear that we need new governance, funding, and remediation strategies for contaminated sites impacted by sea level and groundwater rise.

Finally, groundwater rise will increase liquefaction and lateral spreading risk in parts of East Palo Alto. Soil liquefaction during intense earthquake shaking causes the ground to sink and shift, which can severely damage homes and roads, ultimately injuring or displacing residents and requiring costly repairs.

What recommendations do SPUR and Nuestra Casa have for policymakers, and are they applicable beyond East Palo Alto?

SPUR and Nuestra Casa developed five recommendations for policymakers to manage and reduce the risks of groundwater rise in the City of East Palo Alto and other impacted neighborhoods in San Mateo County. Many cities on the Bay shoreline will face these risks, and several of the recommendations can and should be applied to other vulnerable communities all around the Bay shoreline.

First, require all city plans and infrastructure projects to assess the risks of groundwater rise and compound flooding.

Second, consider adopting Shallow Groundwater Rise Overlay Districts, which specify design and retrofit requirements for underground infrastructure, roadways, and new shoreline development in high-hazard areas.

Third, update guidance, in partnership with impacted communities, for remediation requirements of shoreline sites to incorporate risks of contaminant mobilization from groundwater and sea level rise.

Fourth, update sea level rise and flood maps to reflect shallow groundwater rise so that relevant agencies can begin planning processes to address it.

And fifth, pursue innovative funding mechanisms to support groundwater rise research, adaptation planning, and implementation projects.

East Palo Alto is not the only community at risk of contamination mobilization. More than 5,000 contaminated sites are at risk of groundwater rise around the San Francisco Bay.

Finally, how did your collaboration with Nuestra Casa shape the research and the report’s recommendations, and what’s next for this partnership?

At the start of this research project, Nuestra Casa connected me with a handful of community members to talk about their experiences living in East Palo Alto. I particularly wanted to know more about the existing flooding issues. The conversations centered on the day-to-day issues they face like housing insecurity, as well as their concerns about safe drinking water, the future of climate change, and the health of their children growing up across the street from a contaminated site. They had never heard of groundwater rise, but they were already experiencing some of the problems that groundwater rise will only worsen. This was an important consideration in the report.

The recommendations developed by SPUR and Nuestra Casa represent no-brainer first steps to addressing groundwater rise. Critically, community organizations and residents must be centered in policy and decision-making so that adapting to groundwater rise does not lead to an undue burden on low-income communities of color through rising insurance rates, utility fees, or increased taxes or in other ways.

Nuestra Casa, with support from SPUR, has launched a coalition of community-based organizations concerned about the impacts of groundwater rise, particularly contaminant mobilization. The coalition includes leaders from Nuestra Casa, Youth United for Community Action, Climate Resilient Communities, Belle Haven Empowered, and the Belle Haven Community Development Fund. The coalition is exploring opportunities for community action on groundwater rise, and SPUR looks forward to continuing to support it.