The State of California has determined that San Francisco’s current zoning regulations will not allow enough housing construction to meet the state-set target of 82,069 new homes in the city by 2031. San Francisco must make changes to its zoning rules by January 2026 to comply with state law.

There’s no question San Francisco needs far more housing — the issue is where to build it. Under California law, cities must demonstrate that their local housing policies and zoning rules create enough opportunities for new housing development to meet current and near-term housing needs — without perpetuating patterns of segregation. It’s exactly this issue that San Francisco must now grapple with.

The city’s current zoning rules strictly limit multifamily housing development on more than half of the available land in San Francisco. The rules are lax in neighborhoods that were shaped by a history of racist housing and community development policies and strict in neighborhoods that were historically whiter and more affluent. Failing to change the rules would continue patterns of racial segregation and would mean far too few homes are built, exposing current residents to increasing housing costs, gentrification, and displacement.

How can San Francisco’s Housing Element — the part of the city’s General Plan that addresses housing needs — help ease its housing crisis? We have answers, starting with what the Housing Element is, how it influences the city’s development, why San Francisco needs so much housing, and why significant changes are proposed for the city’s northern and western neighborhoods.

What Is the Housing Element?

The Housing Element is a section of San Francisco’s General Plan that provides a policy framework and an actionable plan to meet the housing needs of all San Franciscans. Under California law, cities must update their housing elements every eight years and demonstrate that local housing policies and zoning rules create enough opportunities for new housing development to meet current and near-term housing needs. Each city receives a target number of new homes to add in a set timeframe. The law does not mandate that all the homes must be built by the deadline — only that the city must change its zoning to allow for and encourage the target amount of housing. The policies must not restrict housing production in a way that preserves patterns of racial segregation.

What Does the Housing Element Have to Do with Combating Racial Segregation?

Housing elements influence community development by identifying priorities for decision-makers, guiding funding allocations for housing programs and services, and defining how and where cities should create new homes for existing and future residents. State housing element law balances allowing cities to control where housing is built with enforcing cities’ obligation to plan to address the housing needs of all residents.

The state is currently experiencing a housing crisis, in part because many local jurisdictions adopted discretionary policies and restrictive zoning ordinances that did not support enough construction to meet communities’ growing housing needs. Many of San Francisco’s restrictive zoning policies were created as an indirect way of preserving the city’s affluent, white neighborhoods after the federal government banned explicit racial discrimination in housing policy. Formerly redlined neighborhoods have been forced to take on more than their fair share of accommodating new housing, leaving many communities to gentrification and displacement. Overly restrictive zoning is the latest in a long line of discriminatory housing policies that concentrated poverty in racial and ethnic enclaves, made it difficult for marginalized communities to access education and employment opportunities, displaced longstanding communities in the name of “progress.”

The State of California has determined that San Francisco’s current zoning regulations will not allow enough housing construction to meet the state-set target of 82,069 new homes in the city by 2031. San Francisco must make changes to its zoning rules by January 2026 to comply with state law.

There’s no question San Francisco needs far more housing — the issue is where to build it. Under California law, cities must demonstrate that their local housing policies and zoning rules create enough opportunities for new housing development to meet current and near-term housing needs — without perpetuating patterns of segregation. It’s exactly this issue that San Francisco must now grapple with.

The city’s current zoning rules strictly limit multifamily housing development on more than half of the available land in San Francisco. The rules are lax in neighborhoods that were shaped by a history of racist housing and community development policies and strict in neighborhoods that were historically whiter and more affluent. Failing to change the rules would continue patterns of racial segregation and would mean far too few homes are built, exposing current residents to increasing housing costs, gentrification, and displacement.

How can San Francisco’s Housing Element — the part of the city’s General Plan that addresses housing needs — help ease its housing crisis? We have answers, starting with what the Housing Element is, how it influences the city’s development, why San Francisco needs so much housing, and why significant changes are proposed for the city’s northern and western neighborhoods.

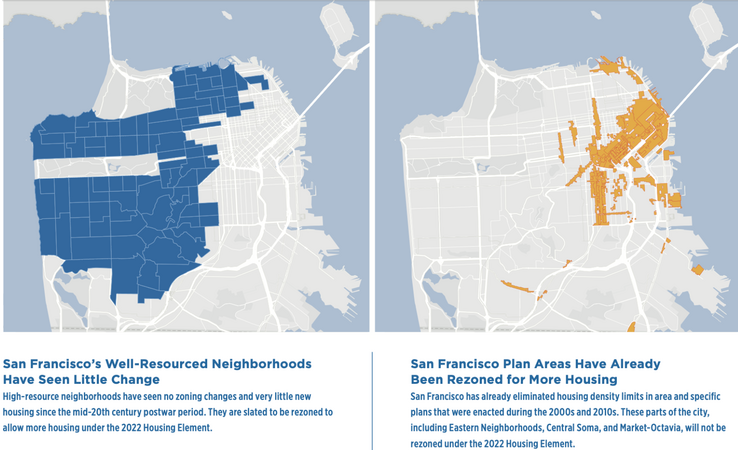

Well-Resourced Neighborhoods Have Seen No Zoning Changes Since the Mid-20th Century

With no zoning changes in more than half a century, San Francisco’s well-resourced western neighborhoods have added little new housing. Northeastern neighborhoods have been rezoned several times this century and have borne more than their fair share of new housing construction.

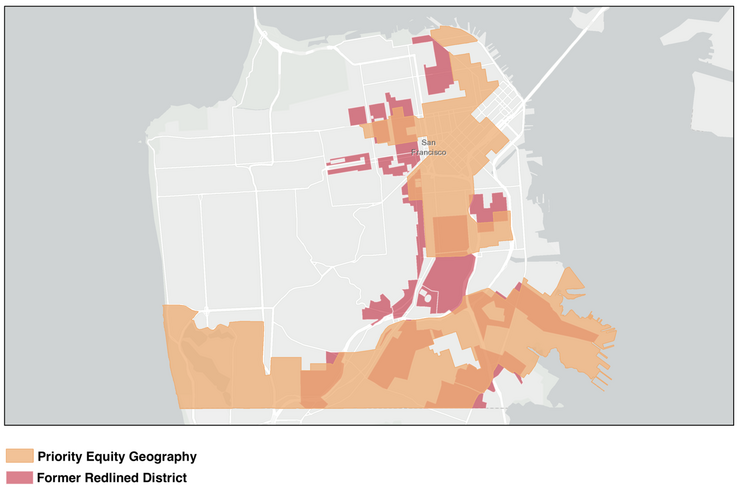

Historic Redlining Shaped San Francisco’s Modern Neighborhoods

During the Great Depression, the federal government evaluated the risk of mortgage lending at a neighborhood level in most major American cities. The agency assigned high-risk designations (color-coded red on maps) to neighborhoods where many African American, immigrant, or low-income households lived, claiming without evidence that the presence of these households lowered home values and mortgage security. “Redlining” these neighborhoods excluded residents from mortgage financing through federal programs and made it extremely difficult for those residents to become homeowners. Private lenders continued this practice for decades. Discrimination also occurred through racially restrictive covenants, which allowed property owners and developers to ban non-white residents from buying or renting housing. In 1968, the Fair Housing Act outlawed these discriminatory housing policies and practices. However, institutionalized racism fundamentally shaped historic urban development and the consequences of de facto segregation continue today.

In San Francisco, demographic analysis demonstrates that many people of color continue to face significant income inequality, low homeownership rates, high eviction rates, exposure to environmental pollutants, and poor access to well-resourced schools and infrastructure. Comparing redlined maps of San Francisco with maps showing neighborhoods where many households are economically disadvantaged or vulnerable to displacement reveals that many redlined neighborhoods never recovered from decades of deliberate disinvestment.

Formerly “Redlined” Neighborhoods Are Home to Many Low-Income Households Vulnerable to Displacement

High-risk mortgage designations assigned a century ago to neighborhoods where many African American, immigrant, or low-income households lived continue to disadvantage those neighborhoods today. Decades of urban development shaped by racism have led many formerly redlined districts to now be designated “priority equity geographies” — areas with a large concentration of underserved populations that need investments to reduce inequitable outcomes.

California Cities Have an Obligation to Affirmatively Further Fair Housing

In 2018, the state legislature passed Assembly Bill 686 to expand existing fair housing protections by requiring cities to administer local housing and community development programs in a way that combats discrimination and fosters inclusive communities. These practices are said to affirmatively further fair housing because they actively support the goals of the Fair Housing Act rather than passively complying with its requirements. The new law changed the housing element process by requiring cities to consider racial and social equity when planning for development and establishing zoning rules.

San Francisco’s 2022 Housing Element was the city’s first housing plan to focus on racial and social equity and to include extensive community outreach. The plan includes commitments to increase housing affordability for low-income households and communities of color and to address housing disparities caused by institutional racism, but existing zoning rules do not support these goals and must be changed in order to comply with the adopted plan.

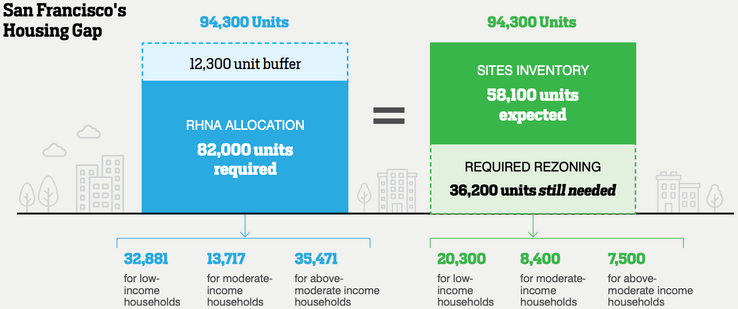

How Did the State Set San Francisco’s Housing Target?

A process called the Regional Housing Needs Determination (RHND) identifies how much housing is needed across different affordability levels for each region in California. It then assigns targets to local governments based on unmet housing need and projected population growth over an eight-year cycle. As part of this process, the city takes an inventory of housing development projects already in the pipeline and the number of units that could theoretically be built on reasonably available parcels under zoning rules. The most recent RHND assessment mandates that San Francisco policies must support the creation of 82,069 new homes by 2031, with a buffer of at least 15% more capacity to account for the uncertainty of development on the potential sites. This means that the city’s zoning rules must accommodate up to 94,300 new housing units.

San Francisco Needs to Build More Housing for All Income Groups

Under current zoning rules, San Francisco would fall short of its housing production goals, missing the mark by more than 30,000 unbuilt homes.

Why Does San Francisco Need So Much Housing?

After the Great Recession, San Francisco saw a boom in job growth from 2009 to 2019, which increased demand for housing in the city. But San Francisco’s discretionary housing policies and procedures restricted housing production, creating a housing deficit that cannot be overcome without drastically increasing annual housing production.

Limited housing availability has made it difficult for low- to moderate-income households to live and work in San Francisco (and other cities) and has contributed to high housing costs, neighborhood gentrification, and the displacement of marginalized communities.

Why Does San Francisco Need to Change the Zoning in Its Northern and Western Neighborhoods?

San Francisco adopted its 2022 Housing Element in January 2023. But the city’s zoning rules do not create enough capacity for the element’s required 82,069 homes to be built by 2031. Current zoning rules prohibit large and mid-sized multifamily developments in most neighborhoods. The few large multifamily developments that have been built recently are mostly in eastern San Francisco, many of them in former redlined neighborhoods. Northern and western neighborhoods represent more than 50% of the city’s total land but only 10% of new housing built in the last 15 years. This stark divide is both a spatial problem — there is not enough available land where sufficiently dense housing can be built to meet residents’ housing needs — and an equity problem because dense and affordable housing is only being built in historically disadvantaged neighborhoods, which limits housing choice for low-income families and people of color.

San Francisco committed to “rezoning” — that is, updating its zoning rules by January 2026 to comply with state law. The Planning Department has proposed an approach that focuses on modifying restrictive zoning policies in neighborhoods close to high-quality transit, jobs, and schools in the western and northern parts of the city to allow more housing in those areas. This approach supports the city’s efforts to meet RHND targets and expands housing options to remedy historic segregation patterns.

How Will Rezoning Help the City?

Some residents fear that allowing more housing to be built will negatively impact their neighborhoods. For communities that have experienced gentrification and displacement due to the housing crisis or that were harmed by heavy-handed urban renewal projects in the past, these fears reflect fractured trust due to real failures of public policy. However, in neighborhoods that have not seen much change, a vocal minority of opponents repeat many of the talking points that were originally used to justify redlining. Claims that building affordable housing will increase crime and make neighborhoods unsafe or that new multifamily housing developments will overwhelm transit and public services are not based on evidence. These myths about rezoning stymie needed reform and can drown out genuine community concerns for vulnerable residents that should be heard and addressed.

Rezoning the northern and western neighborhoods will not result in immediate or widespread redevelopment, it will simply remove barriers and create opportunities for new housing to be built throughout the city. Building new housing in these high-resource neighborhoods would expand access to transit, jobs, schools, and neighborhood amenities that has been effectively withheld from many people who live and work in San Francisco. In exchange, new residents will support local businesses as customers and employees, increase transit ridership and revenue, and boost enrollment and property tax revenue for local schools.

What Happens If San Francisco Doesn’t Rezone?

Current zoning rules maintain an unsustainable housing market that drives families out of San Francisco, leading to declining patronage of local businesses, transit ridership, and school enrollment while increasing housing costs, gentrification, and displacement. San Francisco neighborhoods have become increasingly segregated, by income if not by race, and this reality will not change unless the city allows more types of housing to be built in all neighborhoods. Failure to reform San Francisco’s zoning rules would allow these social and economic problems to worsen and would expose the city to punitive measures from the state.

If San Francisco does not update its zoning rules before January 2026, the state may decertify the city’s Housing Element. Without a certified housing element, the city would be ineligible for state grants that represent hundreds of millions of dollars in funding for affordable housing, street paving, transit, and other key city services. The state may also remove San Francisco's local control over housing to allow “builder’s remedy” projects. Under the builder’s remedy, the state would allow the city to apply only health and safety building codes — not zoning rules. Consequently, the state could approve developer projects that violate existing height, density, and setback rules. The state has already approved builder’s remedy projects and imposed other penalties on cities without certified housing elements, including Menlo Park, Palo Alto, Redondo Beach, and Santa Monica.

What Happens Next?

The Housing Element cannot serve all San Franciscans until the city’s zoning rules realistically address its unmet housing needs. The endeavor to produce enough housing across different income levels should be shared equitably among all neighborhoods. Adopting updated zoning regulations sooner rather than later will give the city the best chance of seeing 82,069 housing units built by 2031.

The San Francisco Board of Supervisors must approve updated zoning rules by January 2026. SPUR will host several educational events in partnership with neighborhood organizations to help answer questions about the proposed rezoning. Please stay tuned for details and join us at one of these upcoming events.