To commemorate the opening of the SPUR Urban Center our inaugural exhibition, Agents of Change, examines the history of citymaking in San Francisco and challenges visitors to consider today’s urban issues in light of their own values. The exhibition, also the focus of this special edition of The Urbanist, covers every major urban planning movement in the city’s history. It tells the story of how the San Francisco Bay Area came to be and frames our current challenges in light of the many successes — and failures — of previous eras. We invite you to meet the people who shaped the city, organized into six overlapping generations: the City Builders, the Progressives and Classicists, the Regionalists, the Moderns, the Contextualists and the Eco-Urbanists.

The City Builders

A city built and controlled by private enterprise

San Francisco was a village of 500 people in 1848, just wrested from Mexico and renamed, when news of the gold found at Sutter’s Mill reached the East Coast. By 1855, the population had reached 50,000.

Nineteenth-century San Francisco went from a rough-and-tumble boomtown to a Victorian city with cosmopolitan ambitions. Its familiar contours emerged as the arid peninsula’s hills were gridded, and its bayshore filled with sand, blasted hilltops and hastily abandoned ships. It matched astounding diversity and relative tolerance with gross inequality and greed, giving rise to an active labor movement marred by spasms of nativist race-baiting and violence.

It was a city built and controlled by private enterprise, and basic services like transit, water and recreation were speculative ventures tied to the city’s rapid growth. City government was corrupt and weak, and party bosses doled out patronage in the form of monopoly franchises for essential services. Private streetcar lines were extended into the dunes, opening adjacent land for rapid development, while the Spring Valley Water Company snapped up watersheds all the way to Livermore.

San Francisco’s development was driven by a small group of oligarchs who ploughed fortunes made in mining, timber and railroads into a new speculative venture: an urban economy based on manufacturing, finance, trade and urban development. These miners, industrialists, financiers and real estate speculators set out to forge a worldclass metropolis in a single generation, enriching themselves in the process. They built the city that would collapse and burn in 1906: an exuberant and frankly ambitious Victorian jumble that was monument to its own explosive growth.

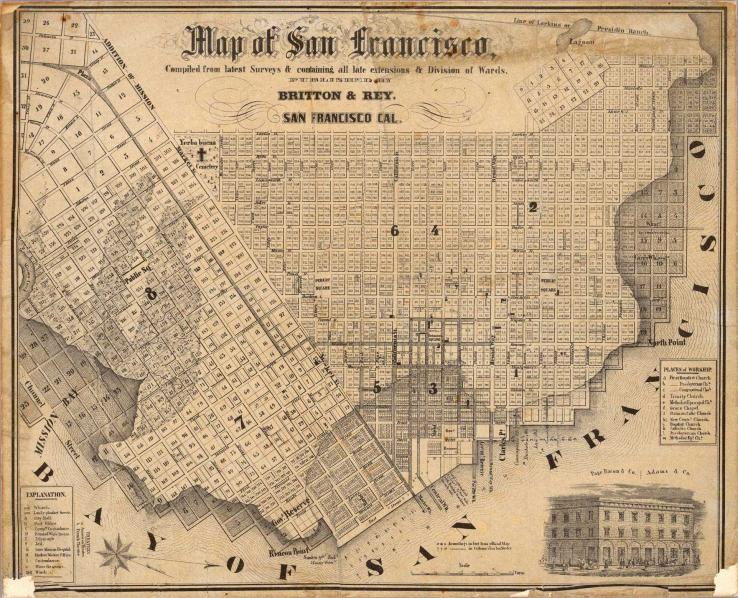

1. The Grid Meets the Hills

The grid that would shape San Francisco’s growth was established by Jean-Jacques Vioget’s 1839 survey, commissioned by Alcalde Francisco DeHaro to regularize land grants in the new pueblo of Yerba Buena. In keeping with common practice, he established a crude grid of 12 blocks around a central plaza, today’s Portsmouth Square. The blocks, which measured 100x150 varas (273x409.5 feet) not only established the street grid, but also the parcelization (into square lots of 50 and 100 varas) that would define building sites and local architecture.

Under American control, the village was renamed San Francisco, and in 1847 Jasper O’Farrell, an Irish engineer, was engaged by mayor Bartlett to extend Vioget’s grid and rectify its inaccuracies. The O’Farrell Plan introduced Market Street, parallel to the Mission Road and a second, larger grid to the south, creating the inconvenient but distinctive intersections that define it today. Most importantly, it established the practice, carried forward in the 1851 Eddy Survey and subsequent additions, of extending the grid without regard to the peninsula’s dramatic topography.

The grid was remarkably efficient for both circulation and subdivision, well-suited to absorbing hordes of new arrivals and to the American view of land as a salable commodity, in contrast to the Spanish land-grant model. The grid did have its critics, however, including O’Farrell himself, who proposed accommodations to the topography and was shouted down. Frederick Law Olmsted and Daniel Burnham would both propose in vain that streets should follow the contours of the hills. The grid’s hold would be broken only in the 20th century, by romantic residential parks and Modernist superblocks.

2. Shaping the Land: Filling the Bay and Cutting the Hills

San Francisco’s distinctive natural features made it a difficult place to build. Sand dunes extended from the ocean all the way into what is now downtown, while steep hills limited both construction and movement. Although the waterfront is among the world’s best natural harbors, the Bay’s natural edge included broad swaths of beach, mudflat and wetlands separating the water from buildable land. These tidelands — now understood to serve vital ecological functions — were considered wastelands and the process of filling them gave the city’s waterfront its current contours.

In 1847 and 1853, 450 “tidelands lots” between Rincon Point and Clark’s Point were auctioned off, raising significant revenue for the new city. As the spaces between the wharves were filled with sand and debris, numerous ships — abandoned by eager 49ers — were buried. North Beach and Mission Bay were gradually filled over the ensuing decades.

The city’s hills presented an even greater challenge as the grid was draped over them, producing streets impassable to horse-drawn wagons. In the 1850s, a maximum street grade of 12 percent was briefly established, but when hills began to be leveled, public outcry produced a more modest solution: a few streets would be graded to ensure access, while the steepest would be replaced by stairs, and hilltop parks would be encouraged. In 1869, Rincon Hill, then the city’s most fashionable address, was bisected by the Second Street Cut, intended to facilitate access to the South Beach wharves. At least one house fell into the sandy, unstable 87-foot chasm, and the neighborhood quickly declined. Many of its residents moved to Nob Hill and Russian Hill, easily climbed by brand new cable cars.

William Chapman Ralston

Perhaps more than any other single figure, William “Billy” Ralston, embodied the ambitions and risks of Victorian San Francisco. Confident, brazen and enthusiastic to a fault, he made a fortune in the Comstock Lode through his Bank of California, founded with Darius Ogden Mills. He invested in factories, agriculture, telegraph lines and shipping while his battles over control of the silver mines roiled local stock markets. Eager to fashion a world capital in San Francisco, he spent lavishly on a huge range of projects, including his own headquarters as well as hotels and a theater. His grandest venture — the $5 million Palace Hotel — would prove his undoing. As his debts mounted, compounded by the Panic of 1873, he made a risky play to buy the Spring Valley Water Company and sell it to the city at a huge profit. When the scheme evaporated in 1875, he was left in deep trouble, which his colleague William Sharon exploited by engineering a run by depositors on the Bank of California. Ruined, Ralston left for his daily swim in the bay, and washed up dead some hours later, while Sharon emerged with most of his assets.

3. The Industrial Oligarchy

Over four decades, a small group of capitalists ploughed fortunes made in mining and railroads into a new speculative venture: the building of San Francisco and a new economy based on manufacturing, finance, trade and urban development. They built and ran private streetcar networks that opened their landholdings to development. They invested in Potrero Point factories and the Spring Valley Water Company. They shaped the political landscape by publishing newspapers like the Call or the Chronicle, bribing officials, or running for office themselves. They built an exclusive social world around their Nob Hill mansions, Belmont Estates and the Pacific Union Club.

The free-for-all of Victorian capitalism favored individuals who could gain control of many different elements of the economy, and a few had staggering reach. They included the so-called “Big Four”—Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins and Charles Crocker — who built the Central Pacific Transcontinental Railroad, later consolidated into the Southern Pacific, which controlled streetcar and steamship lines.

While hardly a monolithic block—many had competing interests and some were sworn enemies—they were a remarkably small and insular group, and shared the sensibility of ambitious frontiersmen who built their fortunes and their city on ruthless opportunism.

Potrero Point

By the 1860s, industrial enterprises moved from North Beach and SOMA, blasting away the steep serpentine of Potrero Point, and using the fill to create the flat, buildable land along its deep-water bayshore. Large-scale manufacturing at Potrero Point (now Pier 70) employed thousands, becoming the industrial engine of San Francisco as its economy shifted from the Comstock mines to the Pacific Rim.

The Pacific Rolling Mills and Union Iron Works created a state-of-the-art shipbuilding facility, alongside Donahue’s gasworks (the basis of PG&E) and Claus Spreckels’ massive sugar refinery. San Francisco’s future lay in Pacific trade and conquest, and Potrero Point built the sugar ships and gunboats that drove U.S. expansion into Hawaii and the Philippines. In the 20th Century, Union Iron Works was purchased by Bethlehem Steel, producing numerous ships through both world wars and BART’s transbay tube in the 1960s.

4. The Speculative Metropolis: Transit, Water and Land

Streetcars and Growth

In San Francisco as elsewhere, urban development was driven by mass transit, which in the 19th century was provided entirely by private companies, which profited from operating streetcars, from the recreational destinations they often served, and, above all, from the development of new neighborhoods on land “opened” by transit access.

By 1851, a private omnibus coach line connected downtown wharves to the Mission via a plank road (now Mission Street) and others soon followed. In 1860, the first horse-drawn railcar line opened into the property of Thomas Hayes (now the inner Mission and Hayes Valley) setting off a flurry of new rail development throughout the city by the 1870s. New tracts of residential development quickly followed. The hills remained exclusive enclaves, out of reach to transit until 1873, when Andrew Hallidie, a Scottish mining engineer, invented the cable car. In short order, even the steepest hills became passable, creating a boom in view lots.

The boom in streetcars and land development drew the interest of San Francisco’s powerful oligarchs, flush from the Comstock mines and the transcontinental railroad. In the 1880s Southern Pacific, led by Leland Stanford, began acquiring streetcar companies. SP consolidated these into a nearmonopoly, the Market Street Railway, in 1893, which was eventually purchased in 1902 by the United Railroads. The graft and labor unrest associated with these companies would drive the municipalization of transit in the Progressive Era.

The Spring Valley Water Company

As soon as San Francisco began to grow, water became a problem. The handful of creeks within city limits were entirely inadequate to serve a large city. Founded in 1858 by George Ensign, and granted the authority to condemn lands for a water system, the Spring Valley Water Company quickly became a powerful and hated monopoly, whose shareholders would include financiers like William Ralston, William Sharon, Lloyd Tevis and William Bourn.

The Company played a key role in the conversion of the dunescape of the Outside Lands into Golden Gate Park, for which it was obliged to provide free water. Under Hermann Schussler, a hydraulic engineer who had made his name in the Sierra mines, the Spring Valley Water Company gradually acquired more than 100,000 acres of watershed, first in San Mateo County (where the Crystal Springs and San Andreas Reservoirs remain) and later into the South Bay and Livermore Valley, from which water was delivered to the city by aqueduct. Repeated attempts to municipalize the company faltered over the price until 1930.

The city’s rapid growth required a larger and more consistent source of water: the Hetch Hetchy system, financed by public bonds.

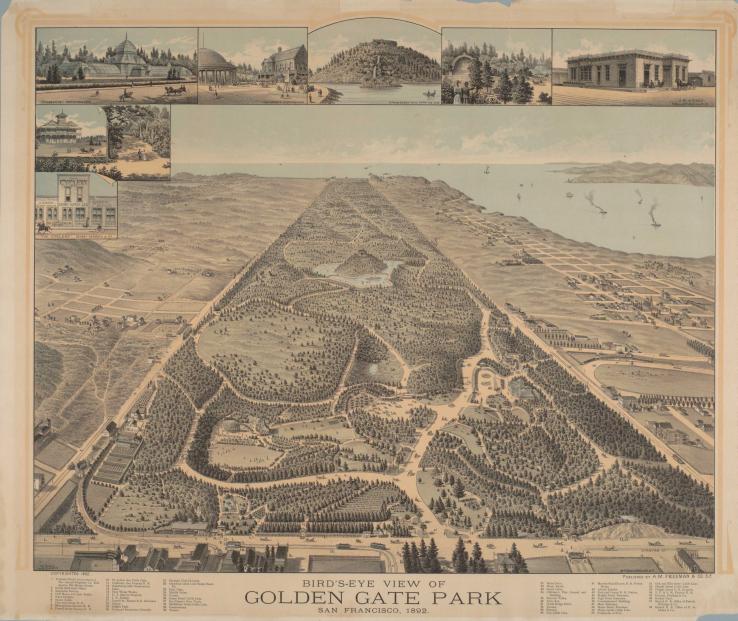

Golden Gate Park

Golden Gate Park was one of the few grand civic gestures of 19th Century San Francisco. New York City’s Central Park, designed in 1857 by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, had recently set the template for the large urban park as romantic landscape. When Olmsted visited Berkeley in 1865, San Francisco hired him to make recommendations for a major open space, the lack of which many boosters saw as a major deficit.

But rather than replicate Central Park, Olmsted suggested an approach rooted in the challenging local climate: a series of smaller parks from what is now Aquatic Park to Duboce Park, connected by a sunken promenade that offering shelter from the prevailing winds.

Olmsted’s plan was rejected in favor of 1,013 acres of dunes in the Outside Lands, where the city had just won title after a struggle with the federal government. Working from East to West, Hall devised a brilliant process of ecological succession, using barley and lupine to stabilize the dunes, after which generous infusions of manure, topsoil, and water (provided under duress by the Spring Valley Water Company) yielded some semblance of the pastoral English landscape the citizens craved.

Immigration and Labor: The Eight-Hour Day

Workers in San Francisco began organizing in the early 1850s, and the city has been strongly associated with union labor ever since. Its relative isolation favored workers, who campaigned successfully for an eight-hour workday in the 1860s. Eight Hour Leagues spread the practice through the trades, and won a statewide eight-hour workday in 1868. The victory, celebrated in spectacular parades, would prove brief, however. The completion of the Transcontinental Railroad the following year brought a flood of workers just as the economy was sagging, and the eight-hour law fell by the wayside.

Many of those workers were Chinese railroad laborers, who ended up in San Francisco factories at low wages and became the victims of racist scapegoating by labor demagogues like Dennis Kearny, who led the Workingmen’s Party after 1877 with the slogan “The Chinese Must Go!” Angry mobs attacked Chinese businesses and speakers railed against the capitalists, especially the Central Pacific, who hired them.

At the turn of the century, labor was again at the center of San Francisco politics, as Mayor Phelan cracked down on striking dockworkers in 1901, propelling Abe Ruef and the Union Labor Party into power. Angry strikes against the United Railroads streetcar company continued, building momentum for a Municipal Railroad and a Progressive resurgence.

The Chinese Experience

Chinese immigrants first came to California in the 1850s to work in mining and later railroad construction. With the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869, increasing numbers of Chinese sought work in San Francisco, and the population of Chinatown swelled to more 30,000, at very high densities of 2-300 people per acre. It was a city apart, with its own language, customs and informal government—the “Six Companies” of the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Society. Ninety percent of the population was male, and prostitution, gambling and opium parlors served both locals and visitors.

In 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, severely restricting Chinese immigration, and Chinatown’s population began to shrink. With Chinese excluded from most of the city, Chinatown remained extremely dense. Public health concerns — some spurious and racist — drove repeated efforts to displace the Chinese. In 1886, laundry owner Yick Wo challenged a law aimed at banning Chinese laundries on equal protection grounds and won, setting an important precedent on racialized zoning.

The Progressives and Classicists

Reforming government and reimagining the city

The turn of the 20th century saw a series of reform movements in reaction to the greed and corruption of 19th century San Francisco. The bald graft and bare-knuckled politics of the Victorian city were abhorrent to the generation that followed, who found the accompanying social ills and labor strife both threatening and morally offensive.

They responded with campaigns to clean up and professionalize city government, municipalize public services, and tackle poverty, disease and other social problems. Social reformers targeted conditions in poor communities through settlement houses and public health campaigns. Many were educated, idealistic children of the Gilded Age, challenging political machines rooted in immigrant and labor groups, and they precipitated a protracted political struggle with overtones of culture and class. But city government’s new transparency and new capacity to deliver basic services, from

the Municipal Railroad to the Hetch Hetchy water system, ultimately served all segments of society better and came to define expectations.

Others had aesthetic ambitions, and put forward grand schemes to remake San Francisco’s businesslike jumble as a splendid Beaux Arts capital worthy of the European models they idealized. Daniel Burnham’s bold 1906 plan neatly coincided with the tragic earthquake and fire. Though the Burnham Plan was sidelined in the rush to rebuild, elements of the City Beautiful appeared at U.C. Berkeley, the Civic Center, and the Panama Pacific International Exhibition.

1. Civic reform

The Progressives’ Bumpy Rise: Phelan, Ruef, and the Graft Trial

The first decade of the new century saw a protracted political struggle between the Progressives and the new Union Labor Party, created by Boss Abe Ruef, who put forward musician Eugene Schmitz to run for mayor, after Phelan alienated organized labor by cracking down on striking streetcar operators. Ruef was a notoriously corrupt political boss, whose machine continued the kind of graft-based politics of the last century.

Progressivism was a complex and contradictory movement. Its social reformers took on poverty and social ills from a position of privilege, and strove to “better” the poor through assimilation. Government reform efforts were often geared toward improving the business climate and breaking the hold of corrupt political machines on City Hall. Its relationship with organized labor teetered from coalition-building to schism to and back again. There is little doubt, however, that they put forward a new vision of how cities should operate: competently, transparently and in the service of stability and prosperity.

After the earthquake, Phelan and his allies initiated trials of Ruef and Schmitz on charges of graft, inducing many members of the machine to testify. Both were convicted (though Schmitz was acquitted on appeal) and Ruef spent time at San Quentin. Although the era of open graft was over, it would take the Progressive until 1912 to take back City Hall.

A New City Charter

The City Charter of 1898 returned home rule to San Francisco after four decades beholden to the State Legislature. It reorganized city government along the civil-service and commission model designed to reduce political corruption and increase competence and transparency. It also called for the municipalization of public services like water and transit. Under the new Charter, San Francisco rapidly recovered from the earthquake, and built Muni, the Hetch Hetchy water system, Civic Center and the Panama-Pacific International Exposition. In contrast, the previous City Hall took 20 years to build, and became a symbol of shoddy construction and graft before collapsing in 1906.

New Institutions: City Agencies, Philanthropic Foundations and Corporations

Many arenas of public life were institutionalized and structured to shift power away from individuals and toward independent bodies. The commissions and civil-service agencies of city government were designed in the period to separate technical professionals from political pressures.

Similar arrangements changed the nature of business, as both government and internal pressure produced a shift away from the massive trusts and family empires of the Gilded Age, and toward corporate governance that divided power among managers, boards, labor and public shareholders.

Philanthropy was also institutionalized in this period, as the families of 19th-Century capitalists—Haas, Goldman, Fleisshacker, Stanford and others—created the foundations with boards, bylaws and endowments, that would underwrite the Bay Area’s nonprofit arts, social service and conservation movements over the coming century.

2. The Earthquake and Its Aftermath

On April 18th, 1906, the political tug-of-war was interrupted, if only briefly, by the earthquake and fire that obliterated much of San Francisco. Twenty-eight thousand buildings were destroyed and more than 3,000 people killed, while a quarter million people were rendered homeless. In the aftermath, Burnham rushed to San Francisco, convinced that a golden opportunity was at hand to implement his plan. Although it was considered, expeditious rebuilding won out over civic beautification and the expense and delay entailed in assembling private property for new streets and parks. Many simply began rebuilding immediately, and the Burnham Plan quickly faded.

Attempts were made to relocate Chinatown to Hunter’s Point and “reclaim” the area for white business. The Chinese community was quick to respond, finding common cause with white landlords who thrived on the neighborhood’s density. They called on the Chinese Embassy, who threatened Governor Pardee with a trade embargo, and they enlisted (mostly white) architects to develop the “oriental” vocabulary of upturned eaves, upper-story loggias, and pagoda-inspired turrets that would appeal to visitors and tourists.

The San Francisco Housing Association and the roots of SPUR

In the aftermath of the earthquake, a rash of unregulated building was producing substandard tenement housing. In 1910, Alice Griffith, who had founded San Francisco’s first Settlement House, the Telegraph Hill Dwellers’ Association, and Langley Porter, a physician, created the San Francisco Housing Association to educate the public about the need for housing regulations and to lobby Sacramento for anti-tenement legislation. The result, following a hard-hitting report by the Association, was the State Tenement House Act of 1911, which created basic standards for health and safety in housing construction.

The SFHA continued to advocate for housing reform through the 1930s, becoming the San Francisco Planning and Housing Association in 1941, and the San Francisco Housing and Urban Renewal Association in 1959. The SFHA’s model of citizen-driven research and advocacy continues to inform SPUR’s work today. SPUR’s good government program area, including fiscal reporting reform, the creation of the Mayor’s Fiscal Advisory Committee, Charter reform in 1994 and its highly-regarded ballot analysis, as well as its research reports on the full range of city issues, can be traced directly to Progressive-era reformers like the SFHA.

James Duvall Phelan

Few figures embody the Progressive Movement in San Francisco— and its contradictions—as completely as James Duvall Phelan. A prosperous and scholarly Irish Immigrant, he had the support of both labor and the wealthy when he was elected mayor in 1896, but could also be elitist and racist. He was passionate about both reforming city government and civic beautification, which he viewed as essential to SFs fulfilling its promise as the Paris of the West.

He led the effort that resulted in the City Charter of 1900, but lost to Eugene Schmitz in 1902 after alienating striking workers with a police crackdown. In 1904, he founded and led the Association for the Improvement and Adornment of San Francisco, to “promote in every practical way the beautifying of the streets, public buildings, parks, squares, and places of SF” Most importantly, this meant engaging Daniel Burnham to develop a long-term plan for the city, which was delivered just before the earthquake. Phelan also served on the Committee of Fifty that led reconstruction efforts and instigated the investigations that led to the graft trials of Schmitz and Abe Ruef. He went on to state politics without seeing his grandest plans realized, but his idealism and civic vision were profoundly influential.

3. Progressive Public Works

The Municipal Railroad

By 1902, San Francisco’s competing streetcar companies had consolidated into a near- monopoly, the United Railroads, widely hated for its corruption and anti-labor policies,. The City Charter of 1900 called for municipalized services, and a public railroad took priority.

In 1912 the City acquired the Geary cable lines, whose private charter had expired. Newly- elected Mayor “Sunny” Jim Rolph opened the system, and its rapid expansion was a popular centerpiece of his 19 years in office. In 1914, Muni added an additional pair of streetcar tracks to Market Street, challenging United Railroads.

Muni became an enormous source of pride, developing new lines to serve the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition and, in 1917, constructing the twin peaks tunnel that opened the city’s west side to development.

Michael O’Shaughnessy

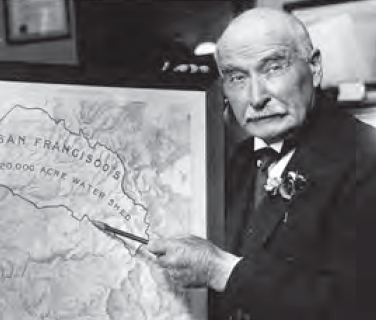

Michael O’Shaughnessy, who served as the City Engineer under Mayor Rolph, embodied the Progressives’ ambitions for a technocratic civil service, free from political and speculative influence. Born in Ireland, he had established a successful engineering practice, which he left in 1912, taking half his former pay. With the help of the new City Charter, he oversaw a massive public works campaign, funded by bonds, taxes and assessments, that was intended both to provide efficient public services and to shape the development of the city.

Michael O’Shaughnessy, who served as the City Engineer under Mayor Rolph, embodied the Progressives’ ambitions for a technocratic civil service, free from political and speculative influence. Born in Ireland, he had established a successful engineering practice, which he left in 1912, taking half his former pay. With the help of the new City Charter, he oversaw a massive public works campaign, funded by bonds, taxes and assessments, that was intended both to provide efficient public services and to shape the development of the city.

He dramatically expanded the nascent Muni system, quickly providing new lines to serve the Panama Pacific International Exposition in 1915, followed by the J, K, L and M lines that are still in operation. He oversaw construction of the Stockton and Twin Peaks tunnels, the latter a 10,000 –foot technical marvel that enabled the development of the southwestern part of the city. His most dramatic achievement, however, was the construction of the city’s municipal water system, which brought Sierra water to the city through a 167-mile system of dams, pipelines and aqueducts from the Hetch Hetchy Valley. He died days before its completion.

4. The Aesthetic Impulse: City Beautiful and the Beaux Arts

While some pursued political and social reforms, other saw civic beautification as the key to a better city. Many San Francisco elites were well traveled, and looked to Europe— and the neoclassical order of the beaux-arts style—for an antidote to the city’s decorative jumble. The hugely successful 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition at Chicago, designed by Daniel Burnham, exposed many Americans to the monumental formalism of the City Beautiful, and to the potential impact of a World’s Fair. The 1894 Midwinter Exposition in Golden Gate park actually repurposed some of its buildings, in addition to constructing the DeYoung Museum and Japanese Tea Garden.

The aesthetic ambitions of this generation were personified by Phoebe Apperson Hearst, who was inspired by her travels in Europe and exasperated with the provincial aesthetics of San Francisco. In 1896, she launched an architectural competition for the U.C. Berkeley campus, which she advertised in European circles. Emile Benard’s winning scheme emphasized formal axes and quadrangles, framed by ensembles of classically inspired buildings. The plan would be carried forward by John Galen Howard, and typifes the aesthetic ideals if the period.

1915 Panama Pacific International Exposition

A World’s Fair had been proposed for San Francisco well before the earthquake, and the idea returned as a way to celebrate the city’s rapid reconstruction as well as the opening of the Panama Canal, which promised to cement San Francisco’s emerging position as an imperial capital on the Pacific Rim.

After some wrangling, 635 acres of Harbor View (now the Marina) and the Presidio were selected, and Edward Bennett, who had been Burnham’s assistant, supervised the design. The centerpiece was the Tower of Jewels, which soared over a series of garden courts framed by ornate but temporary exposition buildings, washed at night by elaborate electrical lighting. The only piece that remains today is Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts, rebuilt in the 1960s. The new Muni lines hat were rushed into service, and the new Civic Center, built that same year, amplified the San Francisco’s pride at this defining event.

The Civic Center

The new Civic Center, constructed between 1913 and 1915, is one of the most complete expressions of the City Beautiful (and the only major piece of Burnham’s Plan) built in San Francisco. Bakewell and Brown’s City Hall dome terminates the formal axis that runs from Market Street, and the surrounding ensemble of neoclassical civic buildings (including the Civic Auditorium, built to house conventions during the PPIE) embody a symmetrical frame to the park.

5. Residential Parks and Garden Suburbs

San Francisco’s grid had been criticized from the beginning as relentless and unresponsive to the city’s topography, but had nevertheless been extended for reasons of commercial and technical expediency. By the turn of the century, the fashion in residential neighborhoods had turned to romantic, curvilinear street plans that followed the contours of the land. Several East Bay and Peninsula districts had been built along these lines, and the Burnham Plan proposed this approach for San Francisco hilltops.

The grid was finally broken in the southwest part of the city, with the development of several so-called “residential parks”, including St. Francis Wood, Forest Hills and Ingleside Terrace. Designed for affluent streetcar commuters, these single-use tracts of Beaux Arts and craftsman houses flourished after the opening Twin Peaks tunnel opened in 1918.

"Sunny Jim" Rolph

Although Phelan was the high-minded purist behind the Progressive ascendancy, it was James Rolph who implemented many of its successful programs. A likeable man and a savvy politician, he was equally at home drinking with working men, launching public works, and schmoozing with the business elite. He was mayor from 1912 to 1931 and presided over the creation of Muni, the PPIE, Civic Center, and the construction of much of the Hetch Hetchy water system.

The Regionalists

Grappling with growth in the Bay Area

In the 1940s and 50s, planners, citizens and business leaders began to view the metropolitan region as a critical scale for both planning and conservation. Wartime industry and postwar suburbanization, abetted by bridges and highways, drove regional expansion and created regional problems, like traffic, smog and the loss of agricultural land.

The nine counties that touch the Bay have 101 municipalities, each with local land use authority, and often in competition with one another. Many important dynamics operate across arbitrary municipal boundaries: job and housing markets, travel behavior, air quality, recreational amenities, habitats, watersheds and ecological processes, even identity and culture.

Planning intellectuals began focusing on regionalism in the 1920s, hoping to manage growth and preserve the relationship of city and country. Citizen advocates, galvanized by rapid bay fill and the loss of open space, organized conservation efforts that spawned the Bay Conservation and Development Commission and the Golden Gate National Recreation Area. Planning for BART began in 1951 and came to fruition in the early 1970s.

But in spite a looming climate crisis, repeated efforts to manage regional growth and its consequences have fallen short of a workable framework, and regional planning is conducted by a patchwork of single-purpose agencies.

1. Early Efforts

The Greater San Francisco Movement

Efforts at regional consolidation have a long history here. As early as 1907, the San Francisco Chamber of Commerce created the Greater San Francisco Association, which aimed to replicate New York City’s recent annexation of Brooklyn. Among other motivations, expanded bonding power would make the critical Hetch Hetchy water system feasible. But Oakland, flush with earthquake refugees and new industrial development, was having none of it (the name least of all). The East Bay was the terminus of inland rail routes, had mild weather and room to grow, and wasn’t about to become a vassal of its charred, frigid neighbor to the West.

A 1912 state ballot initiative on consolidation was roundly defeated. Projects of regional concern would henceforth need to be undertaken by voluntary single-purpose metropolitan districts.

The idea of regional planning emerged in earnest in the 1920s, when the Commonwealth Club, inspired by efforts in New York and Los Angeles, launched what would become the San Francisco Regional Plan Association. Led by earnest, patrician Frederick Dohrmann, Jr, the SFRPA presciently identified the emerging region’s critical needs, from transit to bridges, airports and open space, but was ahead of its time and failed to resonate broadly.

2. A Region Emerges: Streetcars, Ferries, and Bridges

By the turn of the 20th century, the Bay Area was beginning to function as an interdependent region. Wealthy San Franciscans had long held country estates

on the Peninsula, where upscale suburbs grew around the Southern Pacific rail line (now Caltrain). Rail lines were complemented by state highways, many based on bicycling routes, after a 1909 bond measure. These became the basis of many major arterial roads once supplanted by mid-century freeways.

The East Bay took shape around the Oakland terminus of the Transcontinental Railroad, the University of California in Berkeley and industrial development in Richmond. But two factors led to a major development boom: streetcar transit and the thousands of earthquake refugees who arrived in 1906. Francis “Borax” Smith used his mining fortune to acquired large tracts of land in the East Bay, where his “Realty Syndicate” developed housing and streetcars in tandem, as well as the Claremont Hotel and Key Route Inn. The Key System, as the streetcars became known, delivered commuters to a ferry pier in Emeryville for the quick trip to the San Francisco Ferry Building. By the mid-1920s, commuters on the Key System and other lines were making 35 million transbay ferry trips per year.

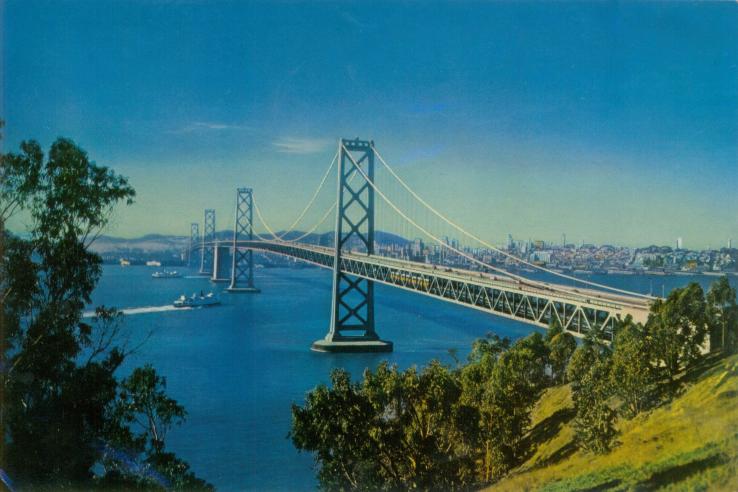

As impressive as the ferry commute was, it was the bridges that finally made the Bay Area a single, integrated region. Imagined and studied for decades, The Bay Bridge (1936) and Golden Gate Bridge (1937) were engineering marvels and sources of immense pride, completed at the height of the Depression. In 1939, the Golden Gate International Exposition was held on newly-constructed Treasure Island, celebrating the region’s integration at its symbolic heart.

The Bay Bridge more than doubled the transbay commute, and though it brought Key System streetcars directly into the newly constructed Transbay Terminal, the tracks were removed in 1958 in an attempt to move more vehicles over the congested span.

3. The Idea of Regional Planning

The idea of regional planning had been emerging in intellectual and policy circles for decades. The British regionalism of Patrick Geddes and Ebenezer Howard found American advocates such as Lewis Mumford, co-founder of the Regional Plan Association of America. Responding to the explosive growth of industrial cities, they imagined a healthy, mutually supportive (and sometimes idealized) relationship between cities and their agricultural and ecological hinterlands, and sought mechanisms to realize it.

These ideas influenced, at least on paper, New Deal programs like the National Resources Planning Council and the Tennessee Valley Authority, as well as Telesis, the influential Bay Area planning group. Telesis, concerned that the livability of the Bay Area was being eroded by sprawl, sponsored exhibitions in 1940 (Space for Living) and 1950 (The Next Million People) promoting comprehensive “environmental design” to rationalize Bay Area development.

During World War II, efforts to organize wartime industrial location, housing and transportation led to quasi-governmental planning entities. After the war, many of these major industrial employers formed the Bay Area Council, to advocate for regional industrial development and infrastructure, including BART.

4. A Giant Leap for the Region: BART

Rapid postwar suburbanization produced traffic congestion, smog, and the threat of declining center cities. Civic and business groups like the Bay Area Council and SPUR (then SFPHA) began advocating regional transit both to organize regional growth and to reinforce the emerging service-based economies of San Francisco and Oakland. In 1951, the State Legislature created a study commission on regional transit, finding that, “If the Bay Area is to be preserved as a fine place to live and work, a regional rapid transit system is essential to prevent total dependence on automobiles and freeways...”

It also stated that any transit system needed to be coordinated with a total plan for the region’s development, but lacked any provisions for regional land use controls. The five-county Bay Area Rapid Transit District was created in 1957, and empowered to raise funds through tolls and taxes. In 1962, San Mateo County supervisors pulled out of the plan. Marin County, unable to bear an increased share of costs, followed suit. Voters approved a revised three-county plan by a hair’s breadth in 1962. Construction began in 1964, and costs ballooned from $996 million to $1.6 billion by the time the system was complete. But the 71.5 mile system, serving 33 stations in 17 cities, was the first major U.S. transit system constructed after World War II. The spacious, carpeted cars and futuristic trains and stations were intended to lure transit-wary Californians out of their cars.

Jack Kent

Jack Kent was among the most influential Bay Area city planners, and was connected with nearly every facet of Bay Area regionalism. While studying architecture at U.C. Berkeley in the 1930s, he was inspired by Lewis Mumford’s ideas on regionalism, which resonated with what he saw in the Bay Area. Traveling in Europe, he encountered both modern architecture and regionalism, visiting Ebenezer Howard’s garden city at Wellwyn. Back in the Bay Area, he worked at the National Resources Planning board, a New Deal agency that espoused regional planning. He was a member of Telesis, where he collaborated with the SFPHA (now SPUR) to promote planning in San Francisco, where, at age 29, he served as the second planning director.

Kent also served on the Planning Director’s Committee, which advised the newly-formed Bay Area Council on regional planning matters, including the need for regional transit. In 1948, he was invited to create U.C. Berkeley’s Department of City and Regional Planning, where he published the classic text, “The Urban General Plan” in 1964.

5. Saving the Bay

From 1959 to 1961 Citizens for Regional Recreation and Parks, newly founded by Dorothy Erskine, sponsored annual conferences through the U.C. Extension on the state and potential of the San Francisco Bay for recreation. In conducting related research, Berkeley planning professor Mel Scott determined that about one- third of the Bay’s 736 square miles had already been filled, and an Army Corps of Engineers Study showed that much of the remainder might be filled before long. The Army Corps maps became the basis of the iconic “Bay or River?” graphic that spurred the Bay conservation movement.

The successful preservation of the Bay can be largely attributed to three remarkable Berkeley women: Kay Kerr, Esther Gulick and Sylvia McLaughlin (pictured below), who became aware of the Bay fill issue when Berkeley was planning a major expansion into the water. They organized Save San Francisco Bay, launching a formidable grassroots campaign that reached thousands and drawing on their political connections (all three were married to powerful U.C. academics and administrators) to reach and enlist State Senator Eugene MacAteer. In 1964, MacAteer tapped SPUR Deputy Director Joe Bodovitz to head a study commission on the issue. The result was the 1965 MacAteer Petris Act, which placed a moratorium on Bay ll and created the Bay Conservation and Development Commission, with Bodovitz as its director.

6. Regional Open Space Conservation

The Golden Gate National Recreation Area: A Citizen Triumph

The Golden National Recreation Area, 75,000 acres of stunning headlands and coast range wildlands, is one of the nation’s great urban conservation areas, protecting some of the region’s defining elements. But although our regional greenbelt is at the core of the Bay Area’s identity, its conservation was the result of a concerted—and recent—citizen campaign. As geopolitics made local defenses obsolete, local military lands came under development pressure, and SPUR had been involved in struggles to preserve Fort Mason, Alcatraz and the Presidio, despite these areas having been identified for eventual park use.

Amy Meyer, an east coast transplant living in the outer sunset became involved in open space conservation when, at a SPUR neighborhood-services meeting, she became aware of a National Archives warehouse proposed for East Fort Miley, near Land’s End. She quickly connected with the Sierra Club and SPUR, and formed People for a Golden Gate national Recreation Area. Amy and PFGGNRA launched a campaign, hosted and mentored by SPUR, that drew in more than 65 organizations and hundreds of volunteers, with the goal of establishing federal protection for 4,000 acres of the most threatened land. In two short years, a flurry of organizing, letter-writing, and advertising created enough momentum to earn the backing of elected officials like Senator Phil Burton, and even President Nixon, whose campaign photo-op on a San Francisco pier led to a Senate hearing for the GGNRA proposal, by then encompassing 34,000 acres as far as the Olema Valley. In October of 1972, the GGNRA became law, and has since grown to 75,000 acres—part of a 175,000 acre greenbelt of protected land at San Francisco’s doorstep.

Conservation Organizations Founded in the Bay Area

• Trust for Public Land• Friends of the Earth

• The Sierra Club

• Earth Island Institute

• People for Open Space/ Greenbelt Alliance

• Transportation And Land Use Coalition/TransAct

• Natural Resources Defense Council

• Urban Habitat

• Goldman Environmental Prize/Goldman Fund

7. Regional Planning and Governance: A Bumpy Ride

In spite of the longstanding recognition of regional problems, there is no public agency empowered to conduct regional planning in the Bay Area. On at least 11 separate occasions, attempts to create some form of limited-purpose regional government have failed. Local interests are loathe to cede any authority to a broader agency, a position that finds legal backing in the State Constitution’s “home rule” doctrine.

Successful campaigns by citizens, political leaders, civic and business organizations have resulted in single-purpose agencies dealing with air, water, open space and transportation at the regional scale. The Association of Bay Area Governments was created in 1961 as a voluntary council of governments charged with regional planning. Although it produced an influential Regional Plan in 1970, with ambitious conservation goals and a focus on concentrating growth in existing cores, it lacks the authority to regulate land use, and the plan remains a path not taken. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission, created by the State Legislature in 1968, is the region’s Congestion Management Agency, is charged with apportioning Federal and State Transportation funds, but not land use planning. In 1971, a bill to combine the two into a single agency failed by one vote. In the late 1980s, a renewed effort, Bay Vision 20/20, conducted an extensive effort to build a regional planning framework, but the resulting legislation failed in 1992.

Meanwhile, the region has expanded well beyond the Bay Area’s nine counties and into the Central Valley, further complicating attempts to fashion a regional planning framework. Between 1980 and 2000, the number of commuters from 12 neighboring counties into the Bay Area nine-county core nearly quadrupled. Region-wide, new commutes are overwhelmingly by auto, far outweighing the growth in transit ridership.

The emergence of global climate change as major policy focus has renewed efforts to address regional growth patterns, which remain uncoordinated and overwhelmingly auto-dependent. The State’s new climate change and anti-sprawl legislation (AB 32 and SB 375 respectively) create new regional requirements and planning tools. Among

other things, SB 375 links transportation dollars to regional land use planning. Its impact remains to be seen.

The Moderns

Destroying the city in order to save it

By the end of World War II, American cities, including San Francisco, were suffering. Fifteen years of Depression and war left a serious housing shortage and

overcrowded, dilapidated conditions in many areas. Automobiles brought

traffic, pollution and accidents to city streets, and the booming suburbs drew families, jobs and investment out of central cities.

But the experts, or so it seemed, could meet any challenge. Planners, including the Telesis group and the San Francisco Planning and Housing Association (later SPUR) had been imagining a modern, rationalized Bay Area since the late 1930s. Driven by socially and environmentally progressive impulses, they saw bold planning as the imperative that could save the city. Housing advocates won federal support for public housing, early examples of which were innovative, livable and well-made. They looked to modern architecture and social housing in Europe, and imagined clearing away the decrepit tenements of the industrial city to create a new city of light, air and open space.

But the approach—wholesale demolition and re-development—produced one of the most traumatic and divisive chapters in San Francisco’s history. It began as a grand coalition of government, business, labor and housing advocates, striving to “save the city.” But over time, both local projects and federal incentives began to look less like social reform in the public interest, and more like commercial real estate ventures at the expense of local communities.

1. Housers and the New Deal

The reforms of the Progressive Era helped create a sense that social problems could

be addressed through regulation, public action and citizen advocacy, backed up by rigorous research in the social sciences. It was against this backdrop that the Great Depression hit, and Roosevelt’s New Deal turned expertise and idealism to the

service of social improvement. Housing was a particularly pressing need, and young advocates like Catherine Bauer and Dorothy Erskine began connecting disparate strands to create a distinctly modern approach to urban housing. They took in Progressive Era tenement reform, social science research and innovative social housing experiments by modern architects in Europe, and forged the policies that would shape postwar American cities.

These “housers,” including the San Francisco Housing Association, were especially outraged by industrial slums, in which poor renters were exploited economically and subjected to overcrowding, disease and pollution. “Slum clearance”— the total demolition of ‘blighted’ districts seemed to be the only solution, and became a progressive byword.

Catherine Bauer

Catherine Bauer Wurster was among the most passionate and influential advocates of social housing in the United States. While traveling, she was exposed to European Modernist experiments with progressive housing and became increasingly convinced of the potential of good design and planning to address human problems. In New York, she had a romantic and intellectual relationship with critic Lewis Mumford, and in 1934, she published Modern Housing, a classic text on progressive housing for low-income people.

Working with the Labor Housing Conference during the Depression, she was a passionate advocate of public housing, and was invited to co-author the 1937 Wagner-Steagall Housing Act, which initiated significant federal investment in public housing and slum clearance. In the late 1930s, she married the architect William Wurster and moved to the Bay Area, where she was a member of Telesis. She died in a hiking accident in 1964.

2. Modernist Urbanism: CIAM and Telesis

CIAM and Modernist Urbanism

The architectural and urban planning response to the industrial city was articulated most famously by CIAM (Congres International d’Architecture Moderne) in The Charter of Athens (1933) which laid out an influential vision of a rationalized, functional and egalitarian city.

Buildings would be placed in parks, away from the noise and pollution of traffic. Large slab towers spaced far apart in pedestrianized “superblocks” would offer equal light, air and greenery to all. Where the traditional city (and the street, its defining element) was fundamentally mixed, the Athens Charter emphasized separation—of housing and industry, of pedestrians and cars— which became a fundamental approach to city planning.

From 75 years’ distance, the Modernist vision can be shocking, and seem basically anti-urban, but it began as an optimistic and socially progressive approach to the dismal conditions of the industrial city.

Telesis

In 1939, a group of passionate young planners and designers began meeting in a Telegraph Hill living room. They called themselves “Telesis” meaning “Progress, intelligently planned and directed.” They were products of the Great Depression, steeped in the ideals of the New Deal, and committed to improving social conditions through betterment of the physical environment.

Many Telesis members became highly influential figures, including Vernon DeMars, Jack Kent, William Wurster, Garett Eckbo and Walter Landor, among others. In 1940, they planned and produced an influential exhibition at the SF Museum of Art (SFMOMA today) entitled “Space For Living.” It challenged visitors to look systematically at the built environment, including decaying inner cities and unplanned suburban development, and imagine a future where the region provided space for “Living, Working, Playing, and Services” without destroying the unique Bay Area landscape.

Telesis members worked with SPUR’s forerunner, the San Francisco Planning and Housing Association, to promote planning and redevelopment, leading to the creation of San Francisco’s Department of City Planning in 1942, the last in a major American city.

Dorothy Erskine: Pioneering Activist and SPUR Founder

Few citizens have ever shown as deep and sustained an involvement in planning and conservation as Dorothy Erskine. A lifelong progressive, she became involved in housing issues, participating in an influential 1938 study of housing conditions in Chinatown, which helped draw federal public housing funds to San Francisco. She met Alice Griffith and helped breathe new life into the San Francisco Housing Association. Through her contact with Telesis, the SFHA broadened its purview and became the SF Planning and Housing Association (SFPHA) in 1942, successfully lobbying for the creation of a City Planning Department. SFPHA also conducted research on the fiscal impacts of “slums,” encouraging San Francisco to initiate a redevelopment program, which the city did in 1948.

Erskine was able to seamlessly navigate the disparate worlds of advocacy, research, government, philanthropy and business. Through her prominent husband, Morse Erskine, she gained access to the upper echelons of the business community, where she tirelessly raised money and drew attention to housing and planning issues. In the 1950s, she became concerned about regional issues, and in 1958 founded Citizens for Regional Recreation and Parks (later People for Open Space and Greenbelt Alliance). A series of conferences the group sponsored was instrumental in launching the Save the Bay movement.

In the late 1950s, San Francisco’s redevelopment program was widely considered to be bogged down and ineffective. Among those pushing for a more effective program was the Blyth-Zellerbach Committee, a group of business leaders anxious about the city’s deteriorating reputation.

In 1959, the SFPHA and the Blyth-Zellerbach Committee brought Aaron Levine, a Philadelphia redevelopment expert to San Francisco to evaluate the redevelopment program. His widely-covered study lambasted San Francisco, placing it 99th out of 100 cities in its attempts to modernize. He recommended new leadership, more autonomy, and an active citizen’s organization to promote Urban Renewal. To that end, the SFPHA was reconstituted as the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association (SPUR).

3. Enter the Automobile

Beginning in the 1920s, the automobile transformed American life. As auto-oriented suburbs emerged on the urban fringe, planners and engineers sought to retrofit the center cities to move and store hoards of new cars. Traffic engineering was a new and quintessentially Modern discipline: quantitative, rational and boldly determined to reorder the world.

The ultimate piece of traffic-moving technology was, of course, the freeway, which eliminated all functions from the street except the smooth flow of traffic. It was based on early experiments with limited-access roadways, including the German autobahn, and partially separated expressways in may parts of the U.S. The true, grade separated, limited-access freeway became the holy grail that would peel auto traffic away from congested city streets, into sinuous, abstract realm of safe, efficient movement. To that end, neighborhoods would be condemned and demolished, and gargantuan structures imposed on the fabric of the city.

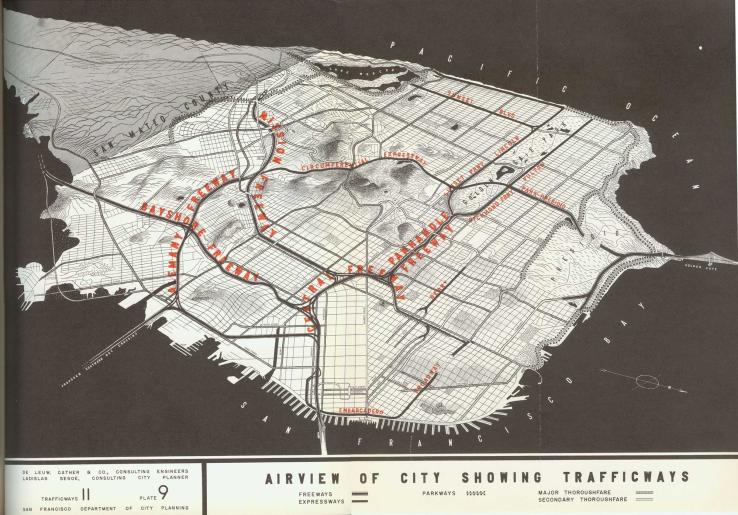

Trafficways Plan (1948)

The 1948 Trafficways Plan is one of numerous versions of a comprehensive freeway system for San Francisco. It includes proposals for freeways up the Pandhandle and on either side of Golden Gate Park, as well as freeway approaches to a proposed Southern Crossing bridge. Many of these proposals were carried forward, but most were cancelled after vigorous citizen opposition.

4. Urban Renewal and Growth Coalitions

Urban renewal (a general term for federally-assisted redevelopment) had its roots in the New Deal, in the sometimes uneasy alliances between public housing advocates, unions and real estate interests. After World War II, downtown boosters and city planners, faced with postwar ur- ban decline and suburbanization, joined these “growth coalitions” in pushing for federal urban renewal legislation to “save the cities”.

The 1949 Federal Housing Act funded additional public housing and created the basic framework for urban renewal, calling for “the realization as soon as feasible of the goal of a decent home and a suitable living environment for every American family.”

Under the program, areas found to be “blighted” by local authorities—“slums”—could be condemned through eminent do- main, and the federal government would pay two-thirds of the cost of “slum clearance” programs. Land could then be bid out for private development. The federal funds created a huge financial incentive for blight findings, especially in poor neighborhoods near downtowns. Amendments in 1954 and 1961 allowed more commercial uses, and urban renewal increasingly emphasized office buildings and convention centers over low-income housing.

Although the 1949 Act required relocation assistance for residents, in practice this was rarely provided. Most residents were poor, minority renters, and tended to be scattered into racially exclusive housing markets where mass demolitions were worsening existing shortages. New development was mostly upscale, far out of reach of those displaced. Because demolition proceeded before development deals were in place, demolished neighborhoods often sat vacant for a decade or more. Urban renewal destroyed far more housing than it built. Anger—and litigation—over its impacts surged, and federal policy gradually grew more inclusive. Under the Nixon administration, the program was finally abandoned in favor of community development block grants, which remains the predominant framework for federal aid to cities.

5. The Deepest Scar: Urban Renewal in SF

Race and Redevelopment

People of color were excluded from most urban neighborhoods by a combination of restrictive covenants and simple prejudice. In the 1930s, the Federal Housing Administration codified such discrimination mortgage underwriting guidelines that excluded “inharmonious racial groups.” This led to decades of decades of redlining, which starved minority neighborhoods of mortgage capital.

In San Francisco, racial discrimination in housing and employment was commonplace, leading to overcrowding and public health problems in enclaves like Chinatown. Racism played a major role in the Western Addition. More than 5,000 San Francisco Japanese-Americans were interned in 1942, forced to sell off homes and businesses. At the same time, large numbers of African-Americans arrived in the city to work in wartime industries, and found themselves excluded from nearly everywhere else. With the war over, industrial jobs declined, and many black workers were shut out of local unions.

The wholesale displacement of the African-American community from the Fillmore coincided with the decline of industrial jobs—more than 8,000 when Hunter’s Point shipyard closed in 1974—and a sustained increase in housing costs. Since 1970, the black population of San Francisco has declined nearly 40 percent, and many African-Americans say they just don’t feel a part of the city.

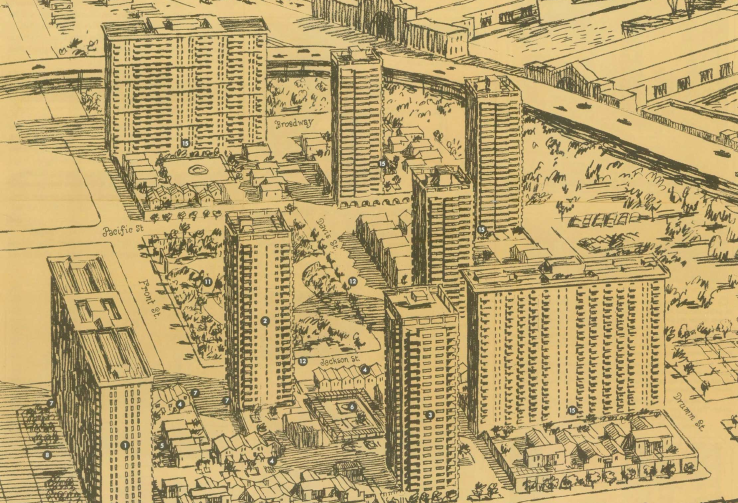

Golden Gateway

The Western Addition

The San Francisco Redevelopment Agency’s clearance of The Western Addition

is one of the most disturbing chapters in San Francisco’s experiment with Urban Renewal. Since the early 1940s, the Western Addition had been identified as in numerous reports as “blighted.” Its aging Victorians were considered outdated firetraps, and many had been subdivided in to tenement units with grossly inadequate plumbing and ventilation.

What advocates of redevelopment failed to notice was a vibrant working-class community, centered on Fillmore Street that supported local businesses and churches and nurtured the West Coast’s most important jazz scene at clubs like Jimbo’s Bop City and Elsie’s Breakfast Club.

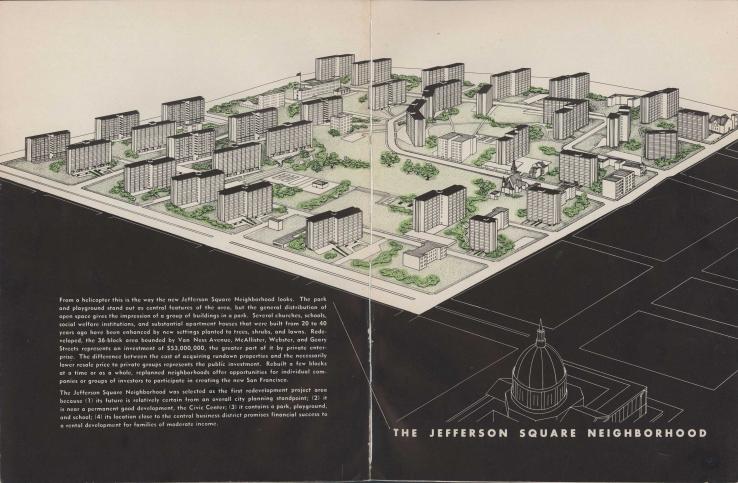

The 28-block A-1 project was approved in 1956, and demolition began the next year. Plans called for luxury apartments, a Japanese Cultural and Trade Center, and the conversion of Geary Boulevard into a six-lane expressway. More than 3,000 families had been displaced by 1960, and the SFRA failed to provide the legally mandated relocation assistance. A rising chorus of objections led to a few moderate-income co-ops developed by unions and church groups, but only one displaced family returned to A-1.

The A-2, a much larger area, was established in 1964, with promises of a real relocation program and an emphasis on rehabilitation. Although a few Victorians were saved, 11,000 units of low-cost housing were demolished and only 7,000 built.

The new housing was generally of poor quality, and the blocks slated for private development sat vacant for decades, a constant reminder of the community that had been. Under pressure from civil rights groups and lawsuit by the Western Addition Community Organization, the SFRA issued 4,729 housing preference vouchers were issued for the A-2 area. Fewer than 1,100 were redeemed, reflecting the lack of available housing and the bitter mistrust many still feel toward the Redevelopment Agency, particularly among African-Americans.

The Contextualists

Protecting the historical city

Many San Franciscans were shocked by the upheaval wrought in the name of "Modernization.” The scars of large-scale demolition and freeway projects, and the apparent disregard for both the urban fabric and local communities, led many to conclude that the “experts” had it profoundly wrong. Around the country, writers like Jane Jacobs and Kevin Lynch began to articulate a new view of the city that embraced its multilayered richness and complexity, where the Moderns strove for rational clarity.

In a variety of different ways, they argued, city planning must take its cues from the existing context. Urban designers began to emphasize close analysis of existing forms and patterns as the most important basis for new interventions while historic preservationists asserted the value of older buildings and launched campaigns to protect them. Activists and community groups insisted that planning respond to the needs and priorities of existing residents, not sweep them aside, and they created new kinds of institutions, like Community Development Corporations and nonprofit housing developers.

Community and preservation groups forged formidable political alliances, and answered the postwar growth coalition with an anti-high-rise and growth control agenda. Many viewed both government and business—historically major instigators of planning activity—with suspicion, and developed a legal and political toolkit for stopping misbegotten projects. The Contextualists pushed for a bottom-up approach that was the antithesis of Modernism: incremental rather than visionary, local rather than comprehensive, and protective rather than transformative.

1. The Freeway Revolt

One of the first and most dramatic episodes of citizen resistance to the Moderns’ brave new world began in 1956, when the Chronicle printed a map of the extensive freeway system proposed for San Francisco, including the Embarcadero and Park-Panhandle routes. The completion of the Bayshore Freeway in 1953 revealed both the seriousness of the plans and the disruptive impact of urban freeways. It was the last freeway completed.

Opposition quickly mounted, and community groups organized and launched petition drives in many affected areas. In 1959, with the Embarcadero under construction, the Board of Supervisors voted to cancel seven out of 10 proposed freeways, but the Panhandle-Golden Gate proposal remained. Sue Bierman, a self-styled “Haight mom,” organized the Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Council (HANC) and led a surge of local opposition, culminating in the project’s cancellation in 1964, by a single vote. It was a dramatic turnabout, inspiring efforts around the country and launching many local community organizations. The stubbed ends of the Embarcadero, Central and 280 Freeways were stark reminders of the episode for decades. The halting and removal of these ill-conceived freeways is among the most widely-celebrated citizen movements in the city’s history.

In 1989, the Loma Prieta earthquake badly damaged the Embarcadero and Central Freeways. The Embarcadero was torn down in 1991. The Central Freeway was the subject of three separate ballot initiatives, but was finally demolished North of Market Street, replaced by Octavia Boulevard.

2. Planning for Whom? Community Development and Social Equity Planning

Yerba Buena Center

For a century, Market Street divided San Francisco’s Central Business District from the workshops, factories, and working-class housing to the South.

By the 1950s, SOMA was an affordable if shabby district of rooming houses and residential hotels, occupied mostly by single older men, retired from industrial and maritime work. Commercial interests began eyeing SOMA for tourist and convention facilities, and after several false starts, plans were approved in 1964. A series of architectural schemes imagined a controlled, inward-looking complex that turned away from the streets and their “undesirable” citizens.

Evictions and demolition began in 1967 with no effective provisions for relocation. But the SFRA had not counted on the will of the residents, many of whom, like George Woolf and Peter Mendelsohn, were radical veterans of San Francisco’s labor movement. In 1969, they organized Tenants and Owners in Opposition to Redevelopment (TOOR) and led suit against HUD to demand affordable replacement housing within the neighborhood. Some labor unions broke ranks with the growth machine, objecting to the displacement of blue-collar jobs and residents.

The court found the relocation plans inadequate and stopped the project, a major victory for poor residents who had been arrogantly dismissed as “bums” and “derelicts”. TOOR drew up its own plan calling for 2,000 units of affordable housing. When the legal battle ended, the SFRA was obliged to plan for 1,500 units of affordable housing and to provide four sites within the area. TOOR was rechristened TODCO (Tenants and Owners Development Corporation) and became a nonprofit community housing developer. TODCO has since developed more than 1,200 affordable units and provides a range of social services for low-income SOMA residents.

Localism and Identity Politics: The Rise of the Neighborhoods

The cultural upheavals of the 1960s gave rise to grassroots organizations in many neighbor- hoods, often emerging from local issues and correspond- ing to the city’s patchwork of ethnicities and subcultures.

A new politics of identity and self-determination inspired organizing and activism among gays in the Castro, Latinos in the Mission, African-Americans in the Fillmore, and Asians in Chinatown. These groups not only asserted control of their own neighborhoods, but they also formed the basis of new political coalitions, led by politicians like Willie Brown, John Burton and George Moscone, who challenged the labor-business growth coalitions at City Hall. Increasingly, San Francisco’s political landscape was framed as “The Neighborhoods” vs. “Downtown”.

A 1976 ballot initiative created district elections for the Board of Supervisors, and 1977 Harvey Milk, Gordon Lau, and Ellen Hill Hutch were elected the first openly gay, Chinese-American and female African-American Supervisors. Moscone and Milk were assassinated the next year.

The Mission Coalition: The Fruits of Community Organizing

The Mission Coalition Organization (MCO) a federation of community groups, emerged from a successful 1967 effort to resist Urban Renewal proposals in the Mission District.

Mayor Alioto then proposed applying for Federal funding under the Model Cities program, and community leaders organized the coalition to establish a local platform and ensure the program met local needs. The MCO was rooted in Saul Alinsky’s community organizing model as well as the civil right movement, and brought together more than 100 different local organizations to find common ground and campaign for community priorities. The MCO established a hiring hall and pressured local employers to hire locally. It organized dozens of tenants organizations, pressured the school district and other public agencies to be more responsive, and created Mission neighborhood plan.

Although the MCO disbanded in 1973, it left behind a remarkable legacy of community organizations and social service providers, many of which are still active.

3. Respect for Pattern: Contextual Urban Design

Shocked by the wholesale demolition of urban renewal, and disappointed with the alien, sanitized environments that followed, many people in San Francisco and elsewhere began to defend the qualities of traditional urban fabric. Often, these were the

very elements the Modernism sought to replace: a mixed and messy vitality, surprise and happenstance, incremental change, social, spatial and functional diversity.

Even as urban renewal projects gained momentum around the country, a few critics, including Jane Jacobs, William Whyte and Kevin Lynch began articulating what was missing/being lost in the modern vision. They put forward nuanced observations of cities’ human fabric: the intimate scale, and fine-grained vitality that was

lost when neighborhoods were demolished and could not be replicated in sanitized single-use environments. In particular, they made an argument for the life

of the street, a complex urban space that is as much a living room, theater, and marketplace as a “trafficway”.

Locally, researchers like Donald Appleyard and Elizabeth Moudon produced in-depth studies of San Francisco’s urban form, tracing its history, and evolution. These ideas resonated strongly among those who found the prevailing views of urban “experts” strangely anti-urban. Allan Jacobs, who served as planning director from 1966-74, personified this new attitude. As an outsider from the Philadelphia, he had both an urban sensibility and a fresh perspective on the conflicts raging over redevelopment. He presided over a department with a far less invasive approach to planning, creating the Urban Design Plan and a series of neighborhood improvements.

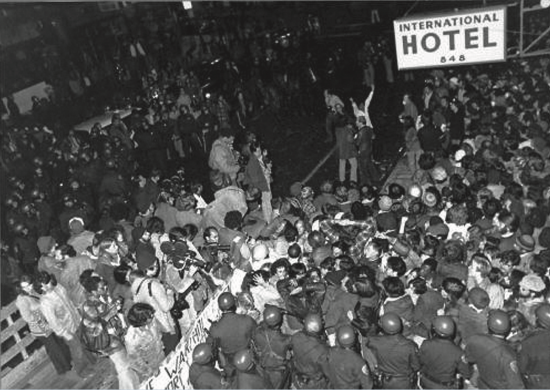

"We Won't Move" The Fall of the International Hotel

The evictions became a cause celebre among a many groups concerned about affordable housing and tenants’ rights. Student activists and an array of political organizations, including Asian, Latino and gay groups organized protests that lasted nine years, through the sale of the property to a Hong Kong investor and the departure of many tenants. Finally, in August 1977, deputies led by Sherriff Richard Hongisto (who at one time gone to jail rather than enforce the evictions) squared off with demonstrators and evicted tenants by force. It was a devastating blow, and further galvanized activists’ sense that commercial expansion was a heartless enemy of urban communities.

4. The Presence of the Past: Historic Preservation

At mid-century, many people did not perceive older buildings—especially wooden, kit-built Victorian houses—as architecturally valuable. They were abundant, out of fashion, and often dilapidated. But by early 1960s, many citizens were becoming alarmed by the wholesale demolition of older buildings, and the lack of a meaningful mechanism for their protection.

Homeowners and amateur historians classified and lovingly restored Victorian homes, and organizations like the Victorian Alliance and Heritage (the Foundation for the Preservation of San Francisco’s Architectural Heritage) began pressuring city government to be more assertive in protecting historic buildings. One of Heritage’s first projects was arrange the relocation of 14 houses from the Western Addition’s A-2 area, then under the wrecking ball. Many public and residential buildings were quickly listed, but older commercial buildings like the City of Paris department store continued to be demolished, leading Heritage to publish Splendid Survivors, a downtown historic survey that influenced the Downtown Plan’s ambitious preservation policies.

Friedel Klussmann

5. “Manhattanization” and the High-rise Growth Wars

In the 1960s, global economic forces led to a shift in the U.S. economy, away from manufacturing and heavy industry, and toward information-based industries such as technology and nance. The Bay Area’s beautiful setting, open culture and major universities positioned it to compete in an innovation economy, by attracting creative, educated workers. San Francisco burgeoned as a “headquarters city” for the emerging service-based economy.

Between 1965 and 1982, the city’s office space more than doubled, to over 60 million gross square feet, resulting in dramatic and controversial changes to the character of the downtown. Many felt that the city’s unique qualities were under siege from what Herb Caen called a “vertical earthquake,” and opposition to high-rise buildings surged. Especially controversial were the Bank of America Building (1969) and Transamerica Pyramid (1972) which were viewed as threatening northward expansions of downtown.

6. The Downtown Plan

The Downtown high-rise boom produced a series of ballot initiatives by growth-control advocates, along with bitter case-by-case fights over new buildings and warring studies on the fiscal impacts of high-rises. A long-term compromise seemed essential, and the Planning Department, led by Dean Macris, set out to develop the city’s first Downtown Plan. The intent was to provide a framework for continued commercial development that would reduce impacts on the downtown’s livability and character, protect historic buildings, and channel growth away from adjacent neighborhoods.

The Downtown Plan created new downtown boundaries, excluding Chinatown, The Tenderloin, and North Beach, and Telegraph Hill, and shifting development south and east, toward the Transbay Terminal and Rincon Hill. It protected 266 historic buildings, and de ned conservation districts, like Belden Alley, where intact pockets of traditional fabric would be preserved. Permitted height and bulk of new buildings zone were considerably reduced, and design guidelines introduced.

The Downtown Plan represented a “grand compromise” in the high-rise growth wars, significantly shifting the location, form, and impact of commercial development, while allowing San Francisco to respond success- fully to global economic shifts that called for a service and innovation-based economy.

Prop M

Ironically, it was immediately following approval of the Downtown Plan that a powerful growth-control initiative finally passed. In 1986, Proposition M capped office development at 400,000 square feet per year and introduced a “beauty contest” to determine what could be built. Its actual impact has been modest, since real estate cycles have kept average annual demand at or near the annual limit.

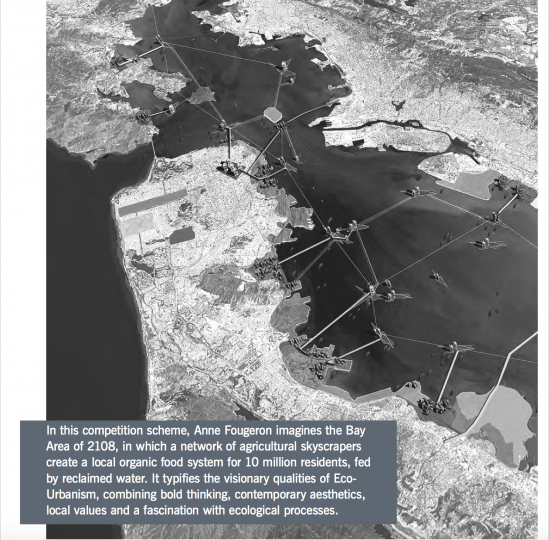

The Eco-Urbanists

Forging a green metropolis for the post-carbon age

The last two decades have seen a reframing of debates over growth, density and change in San Francisco. For many critics, the growth-control policies of the Contextualists have enshrined an essentially conservative attitude toward the city, unsustainable in the context of a crippling housing shortage, explosive regional sprawl,

and a looming climate crisis. A new generation of activists and planners view density at the urban core as the critical ingredient in a more sustainable, equitable and prosperous Bay Area.

This movement is built on a simple insight: city dwellers have a much smaller ecological footprint than their suburban counterparts. They drive

less, live in smaller, more efficient homes, and share public amenities. Eco-urbanism celebrates the virtues of traditional city neighborhoods, but also strives to add new districts that are compact, walkable, inclusive and efficient, translating growth into urban vitality and public life instead of traffic and pollution. It seeks a more accessible city, through ambitious improvements in transit and cycling infrastructure, and new strategies to bring down the cost of housing.

Buildings, streets, and public spaces are challenged to engage the problems of energy, water, waste, and climate, modeling the complex interconnectedness of ecological systems. It is a vision that offers a way forward, an affirmative agenda that strives to internalize the lessons of earlier generations while turning to face our immense common challenges.

1. A New Attitude: From Growth Control to Smart Growth

The past 20 years have seen a broadening in Bay Area environmental consciousness beyond the conservation of nature toward sustainable development. In the late 1970s and early 80s, a few green visionaries took an interest in the integration of ecological systems and dense urban communities. Later, in 1989, a group of planners and architects created the Ahwanee Principles for Resource-Efficient Communities, laying out basic concepts for the creation of compact, walkable mixed-use neighborhoods. These became the basis of the influential 1996 Charter of the New Urbanism, which brought sound planning and community design fundamentals to a wide new audience.

Bay Area environmental activists also began turning their attention to infill development

as the essential counterpoint to conservation. Urban Ecology published “Blueprint for A Sustainable Bay Area” in 1996 emphasizing links between density, affordable housing and transit. The Greenbelt Alliance, Bay Area Transportation and Land Use Coalition (now TransForm) and Livable City, have taken similar stances, a shift that has at times caused tension with those who view development as the enemy of conservation.

2. The Case for Density: Climate, Sprawl, and the Built Environment

San Francisco’s 2004 Climate Action Plan sets an ambitious emissions-reduction goal: a 20 percent reduction from 1990 levels by 2012. Thus far the pace of implementation is not likely to meet the target. SPUR recently released a major study comparing implementation options by cost and effectiveness. The two largest sources of greenhouse gases—cars and buildings—are closely linked to city planning decisions. Adding 40,000 households to transit-rich San Francisco (10 percent more than ABAG mandates) would result in a reduction of 218 million vehicle miles traveled. Job growth in San Francisco would also have a major impact, since 50 percent of downtown, San Francisco workers commute by transit, more than five times the regional average.