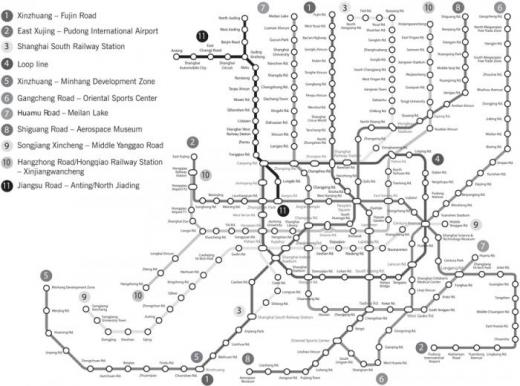

Shanghai is China’s urban showcase, and transportation is one of its showpieces of scope, scale and speed. A decade ago, the city had one subway line. Today it has a grid of 11, covering 260 miles and averaging more than 5 million passenger trips a day. By 2020 all those numbers will double. Shanghai is also a hub for the world’s largest high-speed rail network. After just three years of construction, the 820-mile Beijing–Shanghai bullet line opened in June — right on schedule.

A year after Shanghai’s World Expo, the city’s sprucing for that impress-the-world event was still evident. Still, public transit is planned for the long term, and most is world class. It’s the only way to serve the transportation demands of a still-growing megacity of 23 million at an acceptable energy cost — and it’s a strident contrast to the shortsighted decision-making that hobbles most U.S. transportation policy.

Riding the Metro

If a trip on a brand-new subway in a foreign city, to an unfamiliar destination, is navigation’s acid test, Shanghai’s rapid-transit system, the Metro, passes. Its spotless, functional stations, with their staffed service counters, feel comfortable. All signs and instructions are in English and Chinese. Platform monitors display arrival times of the next three trains — to the second. Navigating the vast underground stations is easy, even when transferring between lines. Above each platform a color-coded graphic indicates which station you’re in (red), where the train is headed (black) and where it’s been (gray). On the train, there are next-station displays, and newer cars have LED route maps above the doors.

Ticketing, which always requires the most passenger decisions, is just as seamless. Just find your destination station and its line on the ticket machine’s touchscreen map, and pay with cash or credit card. Touch your plastic ticket to the gate reader, and go. Use your added-value ticket on taxis, buses and ferries. Like BART, Metro charges by distance: A single trip costs between 45 cents and $1.10, and Metro says it recovers 80 percent of operating costs from fares. (BART receives 65 percent of its operating budget from fares, the best recovery rate in the Bay Area.)

Meanwhile, Shanghai has not neglected its bus system. Up at street level a thousand bus lines await, the biggest network in the world.

High-speed rail

Shanghai is a hub of China’s rapidly expanding high-speed rail (HSR) lines, which were bought from manufacturers around the world. As part of the deals, China required technology transfer, so now it can build and operate its own systems — as well as others in places like Brazil.

The new Beijing–Shanghai bullet line, which cuts the nearly 10-hour travel time in half, expects to carry some 220,000 passengers a day. At peak, trains leave every five minutes. It’s the latest addition to the world’s largest HSR network, covering more than 5,000 miles today — and double that by 2020.

HSR is planned, financed and run by the government, which accelerated construction during the 2008 recession. In a country where nearly a billion people don’t have toilets, authorities justify such premium-cost (though still subsidized) passenger travel as making China more competitive in the long term, creating jobs (110,000 for Beijing–Shanghai) in the short term and freeing older rail for more profitable freight. The government claims HSR reduces urban sprawl by linking urban centers that have connecting subway lines, but if those subways go to distant, expensive and lightly populated suburbs — as do some of Shanghai’s — that benefit is muted.

From 2000 to 2006, national officials debated whether to use magnetic levitation technology or steel rail for the national passenger system. Maglev lost. Shanghai’s Maglev line takes seven minutes to run 19 miles from Pudong International Airport to downtown, but weak connections at both ends make a taxi trip just as fast door-to-door. It’s more a legacy demonstration project, like the Disneyland monorail.

There’s another rail anomaly in one of Shanghai’s new towns, Lingang, at Shanghai’s coastal tip. Designed by the German firm gmp, the town is overscaled, autocentric and quite empty today. But it has a critical function: It’s the logistics center for the world’s largest deep-water port, Yangshan, out in the mists of the East China Sea. Oddly, Lingang and Yangshan are linked across the shallows only by the 20-mile-long Donghai Bridge, not by rail, which means that millions of cargo containers must be carried by trucks.

To TOD or not to TOD

Despite the government’s clear focus on building transit, there is no explicit goal to concentrate development directly adjacent to stations. But because densities are so high, the lack of transit-oriented development may not matter much. There is in fact lots of transit near new development.

One place where Shanghai planners are actively connecting transit with a plan for development is Hongqiao International Airport, 10 miles west of downtown. Abutting the passenger terminal is a rail station with 30 tracks for high-speed trains; two (soon to be three) subway lines to downtown, one of which continues to Pudong International Airport; four expressways; acres of taxis; and a planned extension of the Maglev from Pudong. It’s a great intermodal center, but will the empty, hazy fields surrounding it really be filled with the planned 6 million square meters (65 million square feet) of transit-oriented development? One SPUR member with extensive experience in China observed that “6 million square meters” is always the target number for such big projects.

Auto fix-ation

China juggles an industrial policy to grow its automotive industry (as in the new town of Jiading, see “Shanghai's regional economy,” page 6) with contrasting environmental and transportation/urban growth policies. “Capitalism with Chinese characteristics” may enable top-down planning of public works, but it also supports the bottom-up aspirations of the new middle class to own a home and a car.

An industrial policy that encourages an automobile industry has significant benefits: the industry is a major consumer of domestically produced steel, rubber, plastics and electronics; a foundation for aeronautics, space and defense industries; a source of industrial innovation and good jobs to feed Asia’s largest auto market, which grew 10 percent annually while Detroit tanked. Status car: Audi A4. Superstatus car: Ferrari, which sells more than half of its output in China.

One evening we passed the same Ferrari multiple times (always in first gear) as we strolled through the French Concession, but Shanghai, with an estimated 1.7 million cars, isn’t as gridlocked as notorious Beijing. One reason: If you want to actually drive your new status symbol, you must win one of the monthly auctions for a license plate. Just 8,000 plates are offered each month, and winning bids top $6,000. No Shanghai plate? Traffic police and highway toll stations will stop you from driving during rush hours. Beijing recently copied the strategy.

Shanghai takes its highway strategy largely from North America: There’s an extensive freeway network consisting of three ring roads and a grid of expressways spaced roughly every seven miles. Most are elevated, and limited to cars and trucks.

Pedestrians and bicycles

Walking and cycling remain important parts of the transportation system. Streets are filled with pedestrians. The biggest shopping street is closed to cars; others have wide sidewalks shaded by plane and camphor trees (festively uplighted at night) that make warm, humid, smoggy Shanghai walkable and comfortable.

For the 2010 Expo, Shanghai transformed the Huangpu River waterfront along the historic Bund district, much as San Francisco did when it removed the Embarcadero Freeway. Shanghai tunneled six of the intimidating 10 lanes of riverfront road, narrowing the surface roadway and expanding its pedestrian promenade into a major open space and public amenity with postcard views of the Pudong skyline across the river.

There are still more than 10 million registered bicycles in the city. Many streets have bike lanes separated from car traffic, and at all hours they’re busier than San Francisco’s Market Street at rush hour. A few years ago, bicycling was considered a symbol of poverty, and Shanghai wanted to ban bikes on streets to make room for more cars. Now the city is starting a bike-sharing program modeled on the one in Hangzhou, the world’s largest, and Pudong officials just announced plans to create a separate pedestrian and bicycle street network over the next five years. Despite Shanghai’s flat topography, about half the bikes have electric motors. While gas engines are prohibited, the electrics have their own downsides — most electricity comes from burning coal, and shoddy battery factories poison nearby residents and workers with lead.

Now if China could just translate some of its transit success to greater environmental protection.