The Shanghainese have built an economic dynamo — and are proud of it. Last year’s World Expo rivaled the Beijing Olympics in creating a transformative new infrastructure.

As a region of 23 million spread over 2,450 square miles, Shanghai can be vast and intimidating. But it is not a strange place, at least not for visitors from cities with 19th-century roots. Its historic center is still a well-scaled walking city with great transit, and it is safe, surprisingly green and serviceably bilingual.

Like Paris, Shanghai divides into left and right banks — historic Puxi and newly developed Pudong — separated by the Huangpu River. Don’t confuse the whole of Pudong with its Lujiazui district, a financial center of overwrought towers and overscaled avenues. Hard to pronounce, harder to walk. The best place to view Lujiazui is from the other side of the river, along the newly rebuilt embankment of the Bund, a stunning set piece of colonial classicism and one of the world’s great urban promenades. This is where the British, French and Americans extracted land concessions in the mid-19th century, the best known of which is the French Concession.

Behind the Bund extends a rough grid of colonial arterials, now crisscrossed with elevated freeways. Surprisingly, the new highways fit in pretty well, with their flower boxes, spectacular lighting and accompanying greenways. All arterial roads are lined with shops, malls and commercial buildings; some, like Nanjing and Huaihai roads, are among the most famous retail streets in Asia. The superblocks between the arterials were historically filled with lilongs, a traditional housing style that is actually a blend of two cultures: British terrace row housing and Chinese courtyards.

It’s easy for Westerners to romanticize the lilong without understanding what it’s like to live in one. Associated with overcrowding and poverty, the lilongs have been the target of demolition, replaced by “towers in the park,” high-rise slabs all facing south, that may be brutal to our eyes but are a step up for many of their residents.

As the low-rise lilongs become an increasing rarity among the concrete canyons, we may see more careful restoration and adaptation of them along with the preservation of other examples of Shanghai’s deco heritage from the 20th century.

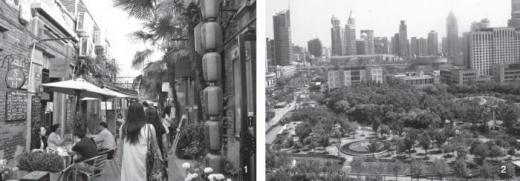

Shanghai already has two good examples to point to, most notably Xintiandi, which, with its rebuilt shikumen stone-gate houses, is now a trendy entertainment center for the affluent and international. Since its restoration, the less-altered lilong settlement of Tianzifang has become a popular and well-visited arts district where residents rent out the first floors of their homes to boutiques and bistros.

Xintiandi — for which SPUR member John Kriken was the master planner — has been so successful with its mix of heritage buildings, corporate towers, high-end condos, all in a car-constrained environment, that slavish duplicates have been ordered up for other metro areas around China. Thanks to these examples of economically successful heritage preservation, Shanghai planners are able to use a combination of bureaucratic insistence and economic appeal to save the past and create sophisticated public spaces — as also demonstrated on Yong Foo Road, where the old British Consulate is now a private club and the centerpiece of a new pedestrian-priority district. The building known as “1933,” a surreal abattoir transformed into an arts center; Bridge 8, a creative cluster in new and old industrial spaces; and the Knowledge and Innovation Community in Wujiaochang are just three examples among dozens that suggest a more creative vision of Shanghai’s future.

Meanwhile, extensive demolition has allowed the city to green up central Shanghai with an astonishing number of parks and public places, including People’s Square, once the colonial racetrack and now the major cultural and civic precinct.

Shanghai’s main defect remains its air quality. Most days are gray, the air filled with dust from inland deserts and unaddressed pollutants. Have Shanghai dwellers ever seen a star-filled sky?

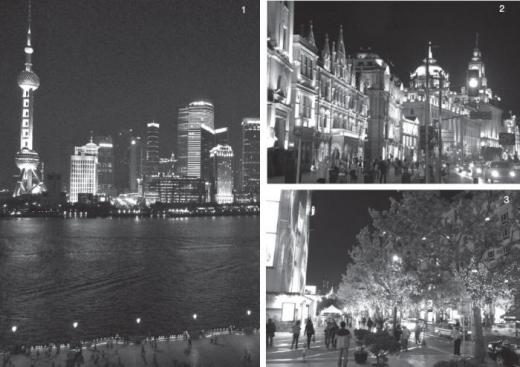

If not, perhaps they are compensating with manmade nighttime lighting. Lumination covers entire high-rise facades on the Pudong side of the river, while the gold-saturated displays of the Bund and Nanjing Road attract thousands on the historic side.Where the elevated freeways cross, the ramps are lined with blue LEDs; along Huaihai Road, the crowns of mature trees are ornamented with glowing red lanterns.

Away from the primary promenades, Shanghai’s sidewalks have to accommodate every imaginable use — and every imaginable small vehicle; seemingly they cannot cope.

One would expect to be frazzled by overstimulation and the claustrophobia of crowds. And yet, most of the time, one is not. Perhaps it’s because of the trees. Has the impact of street trees ever been more significant? The French Concession overflows with London plane trees.

Cleverly, the Chinese use their expressway rights-of-way as tree farms, growing the seedlings to a size where they can be transplanted throughout the region.

Which leads to the question that jumps out when the tourist leaves the center of historic Shanghai for the new towns and development areas: Why have the Chinese planners, and their international consultants, learned so little from the success of these Shanghai traditions?

The question arises again and again, on the vast boulevards of Lujiazui surrounded by desolate plazas; in the new towns, on avenues without bike lanes; in a neoclassical college campus without apparent student life; or at the world’s largest skateboard park, where the only occupants are those watering the shrubbery.

1) Shanghai sidewalks accommodate many uses 2) Tree-lined street in French Concession 3) Plaza outside the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum in Lujiazui

It’s not without precedent. The Parisians built La Defense, the Viennese designed Donau City — modernist megaprojects that even their creators don’t like. It’s hard to understand why the Chinese, scavenging the world for the best examples of urban design, would choose these sterile models for some of their new towns. Shanghai mounted a world’s fair that washed itself in green, constructed 10 major transit lines simultaneously and filled its streets with greenery and its bike lanes with the latest electric technologies. Yet the Shanghainese are saturating their urban environment with thousands of new cars, trucks and buses, celebrating this achievement in car ads as they elevate the expectations of the rising middle class. And so now they find themselves in gridlock.

Why? Maybe because they believe they can solve the congestion, energy and environmental problems after they catch up with us? Or simply because they believe this is the way to build the city of the 21st century.