Not so long ago, it seemed to many that New Orleans might be done for, the first city to succumb to the existential threats of our age. But a decade after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans is decidedly not dead. The Crescent City is back, and in fact, it may be better than ever.

Ten years ago, New Orleans was in ruins

The headlines were about the worst natural disaster in American history, but human error was as much to blame.

The truth is, the city had been declining in plain sight since the 1960s. Though a beloved and culturally vibrant place, New Orleans was depopulated, with corrupt leadership, a shrinking economic base, high-income inequality, the worst public education system in the country, and crumbling infrastructure. Hurricane Katrina missed the city on August 29, 2005, but New Orleans flooded catastrophically because of failures in the engineering and maintenance of its patchwork flood protection system. Nearly 80 percent of the city’s residences were damaged or destroyed, and vast areas of the city were virtually uninhabited for months. The people of New Orleans experienced a traumatic diaspora; less than half of the population had returned a year later. To many, it seemed impossible that the city would recover.

But that’s not what happened.

Instead, something remarkable has transpired. A decade later, New Orleans has the feel of a boomtown.

The numbers may not tell that story: The population is still 15 percent below its pre-Katrina size, which itself was far lower than New Orleans’ 1960 peak, and the regional economy remains heavily dependent on volatile sectors like hospitality, oil and gas and shipping. But there is a striking sense of optimism and renaissance pervading the city. The population has increased more than 11 percent since 2010, making New Orleans one of the fastest growing cities in the country. It is one of the top destinations for college graduates and is experiencing a surge in entrepreneurship and investment. The Greater New Orleans economy is diversifying, becoming a national leader in emerging sectors like biosciences, software development and environmental engineering. The city’s public education system has been transformed from one of the worst nationally to a model looked at by urban school systems all over the country. Major social justice issues remain, like the excessive rates of black male incarceration and unemployment, and new challenges with housing affordability. But given where New Orleans was 10 years ago, the city’s recovery today is remarkable.

How did this happen? How did a city brought to its knees rebound to where some are saying it’s now experiencing a golden era?

There is no doubt that Hurricane Katrina had a catalytic effect. When a delegation from SPUR visited New Orleans in May, we heard it said over and over that the deluge of 2005 was the worst thing that ever happened to New Orleans. 1,464 people died within the city, 80 percent of the city flooded and the social fabric was damaged by leadership failures, toxic media narratives and diaspora.

We heard also that opportunity had arisen out of tragedy.

Throughout our trip, people tried to explain the “Katrina effect” with analogies: a person who has a massive heart attack and changes their lifestyle; a company that goes into bankruptcy and then gets taken over by new management. In the case of the city, the catastrophes of August 2005 exposed the insular cronyism in government that had enabled incompetence. Several of New Orleans’ most prominent pre-Katrina politicians have been indicted on corruption charges — including the previous mayor, who is currently serving a 10-year jail term.

The disaster provided the context for a nearly complete replacement of city leadership and accompanying that, a massive infusion of cash. The federal government has spent $71 billion in Southeastern Louisiana since 2005, and these funds have been spent on creating an enhanced levee system, repairing and rebuilding roughly 100,000 homes, re-laying thousands of miles of roads and bridges, and kick-starting an economic boom with new anchor institutions like the brand new university medical center about to open on 100 blocks in the middle of the city. Large national foundations and businesses, which had long ignored New Orleans, provided enormous grants and investments as well.

Perhaps most importantly, though, has been the surge of civic engagement in the wake of the storm and flooding. As every level of government proved to be incompetent, people took control of their own destinies. The people of New Orleans supplied each other mutual aid, united in neighborhood groups, and assumed leadership in rebuilding and planning for the future of the city. They were supported by a remarkable influx of people from around the country — construction workers, teachers, architects, organizers and innovators — who had in common a desire to help rebuild the city. These newcomers may have initially come either as volunteers or temporary aid workers, but a lot of them have stayed. The people of New Orleans – natives and newcomers - have been a vital part of its recovery and a part of the spiritual renewal that has lifted the city.

The recovery planning process

There have been many plans for the reconstruction of New Orleans and its neighborhoods, but what actually happened is a result of many different actors’ initiatives. The core challenge to reaching consensus about the future of the city was the confrontation between two sets of truths: the reality of environmental threats on the one hand, and the truth about racism and power on the other.

The reality of environmental conditions meant that the low-lying areas of New Orleans were at greater risk of flooding and ones that geographers and planners would recommend not rebuilding on. The truth of racism and power meant that many of these areas were majority African-American, so not rebuilding would mean forcible destruction of neighborhoods of color.

This contradiction exists side by side with another duality: that Hurricane Katrina and the subsequent flooding of 80 percent of the city was both a natural and a man-made disaster. New Orleans exists in a region that experiences regular tropical storms, and the threat of extreme storm events is increasing as the climate warms and the seas rise. At the same time, the catastrophic flooding of the city in 2005 was a result of the failure of infrastructure that was known to be aging and weak, and the impacts on the city and its residents were made worse by the inept response of government officials in the aftermath of the disaster. Hurricane Katrina was also “man-made” in the sense that humans have imposed rigid structures of control on the delta environment over the past few hundred years. This has had the effect of putting the area at greater risk of catastrophe from extreme weather events.

The two truths about the natural and man-made causes of the disaster and the two truths of environmental and social conditions were the core tensions in plans for where and how to rebuild the city.

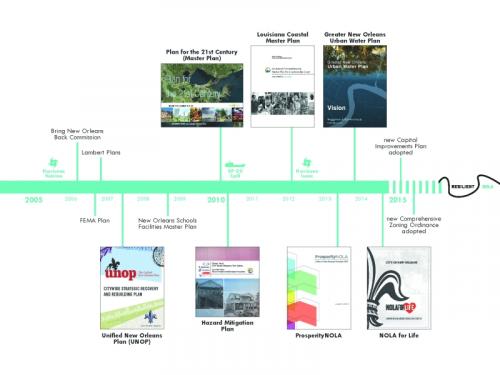

Post-Katrina planning in New Orleans

Though there were many plans for the reconstruction on New Orleans and its neighborhoods over the last decade, what has happened has been a result of many different actors' initiatives. Source: City of New Orleans.

The first of the prominent plans to grapple with rebuilding the city was created by the Bring New Orleans Back Commission, part of which came to be known as the “Green Dot Plan.” Its organizing land use principle was to shift the population of New Orleans out of the unsafe areas that routinely flooded — areas of “repetitive loss” identified with a green dot on the map — and onto higher ground. The central ethical argument was not to put people back in harm’s way. Many planners embraced this concept of “higher densities on higher ground” as the best way to ensure the city’s sustainability. But in practice, the concept had fatal flaws. First, the legacy of race and class injustice in America combined with the city’s topographically-determined settlement patterns had meant that many of the most at-risk areas in New Orleans were the predominantly working-class and African-American neighborhoods. This, combined with the fact that the Bring New Orleans Back Commission was chaired by one of the wealthiest developers in town and had almost no community participation process, fueled outrage. The plan was perceived as a stealth move to rebuild a white city. Further, such a movement of people would have required massive application of eminent domain and buyouts, a sweeping authority over private property, the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the era of urban renewal. Even if there were the mechanism and the money, there was not the political will to do this.

The “green dot plan” was abandoned as quickly as it arose, and subsequent plans had major problems as well. A plan assembled by FEMA was essentially a catalogue of projects. The Lambert Plan focused on the “wet neighborhoods” but was criticized for failing to consider the city’s systems comprehensively. Finally, the Unified New Orleans Plan (UNOP) created in 2007 initiated a neighborhood planning process that would stick. The plan’s organizers placed community input at the core of their work, holding public congresses in the cities across the country where New Orleans’ displaced citizens were living. The resulting neighborhood plans became the basis for the New Orleans master plan — the Plan for the 21st Century — adopted in 2010 and the Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance passed in May 2015.

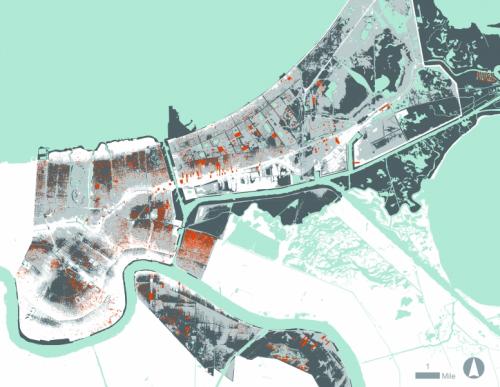

Vacant land and high-risk flood zones

The locations of vacant parcels in New Orleans today corresponds to the most flood prone areas. The laissez faire reconstruction of the city has, in this sense, respected the areas of highest risk. Source: New Orleans Redevelopment Authority.

The New Orleans Master Plan is a huge achievement for the basic reason that it was the first time New Orleans has had a predictable land use plan, built on robust citizen engagement. It is the outcome of the people of New Orleans taking steps to fix the city’s broken system of land use and zoning. For generations, planning had been subverted by a city council that could, and did, regularly amend the zoning map at will. After Katrina, citizens engaged with a renewed activism in neighborhood planning. One of the results has been the development of a citizenry that is conversant in the language and tools of planning. They also wanted the planning they had participated in to be meaningful. In 2008, the people of New Orleans passed an amendment to the city charter giving the city’s land use master plan (the general plan) the force of law. By requiring that zoning conform to the master plan, the reform was meant to ensure that consistent rules, grounded in a community process, were what guided new development. The package of reforms made it harder for council members to insert surprise amendments and exemptions for specific projects. Reforms also created a new, formal public participation process. Developers must now bring new projects to the neighborhood. Citizens have avenues to weigh in at the beginning of the land use process rather than the end.

The enacted plans have been cautious about the most contentious subjects: flood risk and urban footprint shrinkage. Ultimately, shrinking the urban footprint by mandate has proved impossible. To paraphrase New Orleans’ preeminent geographer, Richard Campanella, it would have been socially divisive, fiscally exorbitant, legally complex, politically untenable, and culturally defeatist. What local politician could or would take this on?

Meanwhile, many homeowners worked through the Road Home program, in which the state of Louisiana provided funds up to $75,000 (initially $150,000) for residents whose homes were damaged. Owners could decide to use the funds to rebuild or to relocate. The most at-risk areas ended up being the areas where the most people chose to sell to the state and move elsewhere. The laissez faire resettlement of New Orleans did somewhat follow the green dot plan pattern, voluntarily. People recognized the danger of rebuilding on a flood plain and through the individual organic process of homeowners decision-making, some of the ideas of the higher-density-on-higher-ground plan were partially realized. But without a comprehensive plan, settlement has been scattershot with individual structures dispersed across open space. This “gap- toothed” phenomenon, also observed in legacy cities like Detroit, Cleveland and Baltimore, has major downsides for delivery of services like transportation, parks and public safety – benefits that could have come with rebuilding a denser city. And there remains the same problem of how to defend an urban footprint that is so big and so vulnerable. The Urban Water Plan for New Orleans and the Louisiana Coastal Master Plan (both detailed in the article on page 10) are the first, exciting steps in figuring out how New Orleans can really be sustainable: by learning to live with water and thinking more expansively about flood control and climate adaptation for the 21st century.

New Orleans population change: 1940 to present

Like many American cities, New Orleans' urban population began to decline in the 1960s. Katrina hit a city already struggling with population loss. Today New Orleans has recovered 85 percent of it's pre-Katrina population and is growing for the first time in half a century. Source: New Orleans Redevelopment Authority.

Behind the plans, a human story

The planning history is important to understanding how New Orleans looks now, but the human story is actually more significant to the city’s true recovery. Underneath the 10 years of formal planning processes was the movement of people passionate about saving the city, and this has been the key driver of the New Orleans rebound. The people of New Orleans have committed the energy and talent – not just to rebuild the city, but to reform it, laying the groundwork for a different kind of long-term stability, prosperity and sustainability.

There have been significant anti-corruption and transparency efforts undertaken successfully since Katrina. The disaster opened the way for reform by both shining a light on the consequences of historical corruption and by galvanizing a renewed civic activism. Over the past decade, legions of citizens, journalists, community groups, business alliances and universities have organized to support reform. Citizens elected a new mayor and governor on platforms of cleaning up the city. They joined with historic watchdog groups like the Bureau of Governmental Research, education reformers, and reconstituted regional boosters like GNO, Inc., which have been steadfast supporters of good government.

An immediate priority in the aftermath of the deluge was the regional consolidation and reform of the many corrupt and incompetent levee boards, whose members were frequently unqualified to monitor the soundness of the city’s flood protection system. A reform movement pushed for professionalizing and depoliticizing the boards. The movement culminated in a 2006 local constitutional amendment supported by 80 percent of voters to consolidate the fragmented levee boards into two regional coordinating authorities with greater independence from the state and city. Instead of political appointments, membership on the board was instead made contingent upon the professional qualifications candidates could bring to the job of keeping the city safe.

The transformation of New Orleans’ schools has been the most remarkable change in the city. As of 2005, the New Orleans School Board was responsible for the worst performing urban school system in the country. During the 2004-5 school year, two-thirds of the schools were ranked as failing; 11 percent of high school students dropped out and another 20 percent of seniors did not graduate. In 2003, the state legislature began transferring chronically failing schools out of local school board control and into a parallel school district, the Louisiana Recovery School District (RSD). After the storm, the RSD took over the vast majority of schools in New Orleans (all but the highest performing) and over the next 8 years converted them into charter schools. Today, over 90 percent of New Orleans students attend autonomous charter schools. The RSD, in cooperation with the Orleans Parish School Board, has put in place regulations to ensure all students are served. Outcomes for students have dramatically improved. Only 7 percent of students now attend a failing school, down from 62 percent in 2005, and the graduation rate is up from 54 percent to 73 percent.

There are many remaining areas of governance in need of reform in New Orleans: criminal justice, expanding the tax base, dealing with the estimated 60 percent of property tax value that is off the rolls, reversing chronic underinvestment in infrastructure, and public pensions. Instituted reforms that have proven effective must be maintained against their reverting back to the old ways of doing things. At this moment, the state legislature is pursuing an effort to weaken the levee board reforms and restore appointments “at the pleasure of the governor,” a move many see as overtly political and driven by oil and gas interests in response to a lawsuit brought against them by the SE Louisiana Floor Protection Authority East.

Above, scattered vacant lots in the Lower Ninth Ward. The Lower Ninth is a persistent symbol of the many issues yet to be resolved in New Orleans recovery: where to rebuild and where to retreat, who recovery has benefited and who it has left out. Photo by Colleen McHugh.

Changing demographics

One of the things one notices upon visiting New Orleans now is the presence of something like an expat community of cosmopolitan, socially-minded Gen-Y-ers. These mostly college-educated, predominantly white transplants have brought with them a ton of cultural capital. Many of them first came as volunteers through organizations like Teach For America and Habitat for Humanity, through their university or church, or through their own initiative. The energy of these returnees and transplants has contributed enormously to New Orleans’ recovery.

Yet, the trauma of the diaspora and the changes wrought to New Orleans’ population must be acknowledged. Before Katrina, New Orleans had a nativity rate of 77 percent, highest of any city in the nation. Residents feel a deep attachment to place — both to the city and to the neighborhoods from which they hail. The recovered population of New Orleans is whiter and more Hispanic. The census estimates that there are about 100,000 fewer African-Americans living in New Orleans in 2013 than there were in 2000. Many people have not been able to return, and those who have find that New Orleans still has a lot of the old problems and has also gained some new ones. The cost of housing is going up because so much of the housing stock was lost, and new, higher paid workers are bidding up the prices of the houses that are available. The city lost most of its public buses in the flood, and the mere 36 percent of the public transportation system that is up and running ten years later disproportionately serves tourists and the wealthier parts of the city. There are still a lot of poor people living in New Orleans, and the majority of the disadvantaged are African-American. Black male unemployment is at 52 percent. The entrenched equity issues and changing makeup of the population provoke the question: who is benefiting from New Orleans’ recovery?

What lessons can be drawn from the New Orleans experience?

It would be a mistake to conclude that there is a sociological law that reform happens more easily after a disaster. In the chaos after a disaster, the foremost desire is to return to a semblance of normalcy. As with examples like San Francisco after the 1906 earthquake and New York post-Hurricane Sandy, the dominant public urge post-disaster is often to recreate the same city, as quickly as possible. That New Orleans is going about things differently now is again testament to its people. More citizens in New Orleans are involved in democratic processes than ever before, and they have stayed engaged through ten years and many phases of planning, rebuilding and reform.

Another lesson to be gleaned from the New Orleans rebound: Reform is easy at first and harder in the middle. Momentum exists early on, aided by advantages given freely from outside. But at some point along the road to full recovery, a person, a company, a place is expected to again compete on its own two feet. This is a distinct test, one it seems New Orleans is ready for.

We heard many people say New Orleans now is like “a start-up city.” Filled with creative energy, a fervor for building from the ground-up, and a sense of being a laboratory for tackling urgent 21st century problems. Certainly, this opportunity to build something, to be a part of a movement, is attractive to many people with idealism and ambition. And there’s something special about the flavor of this enterprising spirit in New Orleans. It’s not abstract – it is rooted in a sense of place and caring about the city.

Ultimately, the most powerful thing we’ve taken from the experience of being in New Orleans is about love. More than planning, more than governance, the condition for whether or not a city is truly resilient seems to come down to people’s care for it. New Orleans still exists because hundreds of thousands of people could not abide the idea of it not existing. So they came back. They came to the rescue. They stayed, even when was hard. New Orleans recovered because people love it.