Photo by Sergio Ruiz for SPUR

Photo by Sergio Ruiz for SPUR

The Bay Area is experiencing a housing shortage that threatens to transform our entire region, undermining our economic competitiveness, our diversity and our environment. The factors that have contributed to our current situation are wide-ranging and well- known, including local concerns about growth and change that make it hard for elected officials to vote for new development, a state tax system that rewards the building of retail and office uses over housing, and skyrocketing development costs. The region has not built enough housing units to accommodate all of the people trying to live here, and as a result we have watched our region become ever more expensive until arriving at the point where we’re at today, where only the wealthy are able to get in, and longtime residents, dwindling in numbers every year, are fighting to hang on.

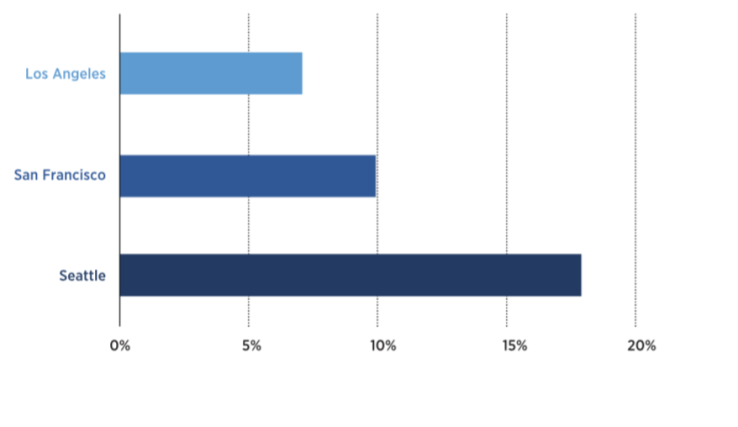

The Bay Area is not alone in facing rising housing costs. All of the big cities on “the coasts” (Boston, New York, Washington, Seattle, Los Angeles and Portland), along with honorary inland members of this club such as Denver and Austin, are experiencing something similar. But we’ve allowed it to get worse here than anywhere else. Renters and homeowners in the Bay Area spend more of their income on housing than anywhere else in the U.S., averaging at over 40 percent in San Jose and San Francisco.[1]

Housing is not a new problem for SPUR, but the problem has changed in surprising ways over the decades. SPUR was originally founded as the San Francisco Housing Association (SFHA) in 1910. The problem then was badly constructed housing put up in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake and fire. The SFHA was part of a broader national “anti-tenement” Progressive reform effort to raise the standard on housing construction in U.S. cities. The first report of the SFHA presented a detailed proposal for raising building standards, which resulted in the 1911 State Tenement House Act. Throughout the 1920s and ’30s, the SFHA was an advocate for public housing, with board members like Alice Griffith and Catherine Bauer working to bring the government into the role of building “social housing,” much as the great European capitals were doing.

As American cities experienced population loss in the decades after World War II, the problems cities faced were not those of of high housing costs, but rather of of concentrated poverty, segregation and lack of investment in the building stock. And public housing (born out of the 1937 Wagner-Steagall Housing Act to improve urban housing conditions) eventually became a program for the urban poor that reinforced segregation rather than the European approach of building government-funded housing for broad swaths of the population.

Then came a shocking reversal of fortune, as certain cities switched from the problems of abandonment and disinvestment to the problems of gentrification and displacement. Cities such found themselves in the quite unexpected situation of too much demand rather than too little. This reality began earlier in San Francisco and San Jose than in Oakland but is now impacting many communities regionally. The problem was that we needed to figure out where all the newcomers could live without pushing existing residents out. And in this fundamental task of urban governance, we have failed terribly. Today, over 80 percent of renters plan to settle outside of San Francisco, and 60 percent cite affordability as their reason for leaving.[2]

SPUR began sounding the alarm in the late 1970s. Following a citywide downzoning and the early signs of gentrification in some San Francisco neighborhoods, it was clear that the city was headed for a housing shortage. A 1981 SPUR report opens with: “San Francisco is in the midst of a severe housing crisis. It is not only the poor, nor only the rich, nor only minorities, nor only corporations, nor only labor who bear the brunt of the housing shortage.” In the 1990s, SPUR convened a group of housing advocates and planners to develop a comprehensive housing reform agenda that would make it possible to get ahead of the growing housing shortage.[3] We called for a new approach to neighborhood planning (which ultimately led to the Better Neighborhoods process), a formalized inclusionary housing law, and reforms to parking requirements, among many other things. SPUR wrote then, that “San Francisco is facing an unprecedented need to create more housing if we are serious about our goals of maintaining economic and demographic diversity.”[4]

The essence of SPUR’s housing agenda is easy to grasp: Build more housing at all income levels. For us this work involves the following steps:

Change the zoning to allow higher-density housing. Place the greatest densities where the transit is best. But also allow small-scale buildings like accessory dwelling units, duplexes and corner- lot apartment buildings everywhere.

Use new development to improve livability, making neighborhoods more walkable and adding amenities.

Fund affordable housing so that low-income people can live here too. Invest heavily in programs to build up a permanently affordable housing stock at a scale that exists almost nowhere in the U.S.

Protect residents in their homes, either by buying units and making them permanently affordable or by using regulations to protect tenants from rapid rent increases, which is especially important during economic booms.

SPUR's suggestions to increase housing stock and density include, clockwise from top left, 1. Allow for the construction of accessory dwelling units. 2. Preserve existing housing stock. 3. Increase area density by building higher density housing infill. 4. Utilize prefabricated building techniques to reduce the cost of construction.

SPUR's suggestions to increase housing stock and density include, clockwise from top left, 1. Allow for the construction of accessory dwelling units. 2. Preserve existing housing stock. 3. Increase area density by building higher density housing infill. 4. Utilize prefabricated building techniques to reduce the cost of construction.Over the past 20 years, we’ve had many victories and many losses. We ran ballot measures that have resulted in billions in funding for affordable housing. We developed reforms to the approval process to make it easier to build housing. We worked for years on getting San Francisco to begin and complete Neighborhood Plans. We learned everything we could from other cities and brought that back.

It has not been enough. We’ve ended up with a housing model throughout much of the Bay Area that others call “the San Francisco death spiral,” a phenomenon “that starts when housing prices start to rise and the only answer regulators devise is to dial up regulations, fees, taxes, and exactions that raise costs, slow production and boost prices. With each successive month over month increase in price the calls for even more regulations, fees, taxes, and exactions grow. The leaders respond. Prices rise. Rinse and repeat.” [5]

We came to understand the housing shortage as a collective action problem in which the decisions of each local government—understandable on their own terms, according to their own fiscal and electoral incentives—have added up to not nearly enough housing for all the people who want and need to live here. SPUR looked hard at its work and decided that we needed to work beyond San Francisco if we were going to make enough progress on housing as well as other regional issues. We opened up offices in San Jose and in Oakland, and we have become deeply involved in those communities. As a result of that decision, we’ve been able to advocate for more housing in San Jose, particularly through the city’s Urban Village process. Last year we helped the mayor of Oakland develop a citywide housing strategy. We will continue to work closely on housing policy in all three major cities.

In recent years, SPUR has gotten more focused on state and regional reforms. The State of California creates the enabling framework for all local planning work, and the state’s tax structure provides the financial incentives that shape cities’ development policies. SPUR believes that the state should adopt a new framework for housing approvals, one that strengthens state housing targets for regional and local governments and makes infill housing easier to build, along with reforming the tax system by letting cities keep more of the residential property tax and rewarding cities that build densely enough in transit- oriented locations.

Other states have undertaken meaningful reforms along these lines already. Oregon and Washington benefit from growth management laws that require cities to allow growth within the existing urbanized footprint and stop sprawl at the edge of their regions. The Minnesota state legislature in 1971 enacted a regional tax-sharing system for Minneapolis–St. Paul that spreads the fiscal benefit of commercial development across the region by pooling 40 percent of the growth of commercial property tax. This takes away some of the fiscal incentive to chase shopping malls. Massachusetts created a state appeals body that can permit housing developments in cities that have not complied with state housing laws. As the housing crisis engulfs more of California, we have become convinced that state reforms have to be part of the solution, even while we continue to work at the neighborhood level to address the housing shortage block by block, building by building.

We’re not going to give up. Housing costs threaten everything about our values. They make it impossible for the Bay Area to be a haven for newcomers from all places, just as they make it impossible for people to take life paths that aren’t financially lucrative. If we continue down the path we are on, we’ll become an enclave of wealth and exclusivity. The epicenter of the crisis may be San Francisco, but from this “worst offender” the shockwaves of displacement radiate across the region.

There are many, many, many more things left for us to do to make housing more affordable for everyone. We have no excuse for not trying all of them.

1. “Housing Affordability in the United States, 2017 Q2,” Zillow research published 8/8/17. https://www.zillow.com/research/q2-2017-housing-affordability-16323/

2. “Moving On: Why Are Renters Relocating?” Sydney Bennett. Published Aug 9 2017. https://www.apartmentlist.com/rentonomics/why-are-renters-moving

3. SPUR Report. May 1992. “Plain Talk About the Housing Crises in San Francisco.” Report 292.

4. SPUR Report. June 1990. “A Recipe for San Francisco Housing?” Report 267.

5. “Seattle’s Next Mayor Must Step Back from the San Francisco Death Spiral,” Roger Valdez, published 7/31/17.