The Bay Area has one of the largest and least sheltered homeless populations in the country. Although this is one of the most prosperous regions in the world, every night thousands of people sleep on our streets. It is deeply dehumanizing to live on the street, and it’s deeply disheartening for everyone to live amid such despair. The social compact that undergirds the function of our cities has been broken.

To some, the Bay Area’s inability to solve homelessness demonstrates the failure of our progressive urbanism — a sign of our unwillingness to enforce standards of behavior on the street — along with our failed housing policy. To others, it is a symptom of a broader breakdown of American society — an expression of deep dislocations in the economy and the extremely high rates of drug use in the United States, along with a sense of despair among large swaths of the population.

Bay Area residents care deeply about this problem. In poll after poll, homelessness is cited as a top concern. Voters have supported various, sometimes conflicting, solutions. In 2016, Alameda, Oakland, San Mateo, San Francisco and Santa Clara Counties all passed bond measures to fund more affordable housing. At the same time, many Bay Area municipalities have passed “sit-lie” ordinances to clear people experiencing homelessness from the streets. While housing solutions, from shelters to tiny home communities to permanent supportive housing, are supported in theory, residents resist allowing them in their neighborhoods. None of us want our most vulnerable neighbors to end up living on the street, yet it seems few of us want them housed next door.

Over the past year, the SPUR Board of Directors convened a study group to learn more about homelessness — both its causes and its possible solutions. We have come to understand homelessness as a symptom of deep structural forces in our society and economy, as well as a result of local policy failures. We may never be able to “solve” homelessness entirely. But we can — and must — do a much better job at preventing homelessness, making it as brief as possible when it does occur and reducing its negative impacts on our neighborhoods.

In order to support the most effective policy solutions to homelessness, we must begin by trying to understand the state of the problem in the Bay Area today and developing a common understanding of its root causes. While it has made some policy mistakes in the past, the Bay Area has some of the country’s most forward-thinking organizations working on homelessness. With stronger political leadership, greater accountability, better coordination, sufficient funding and broader community support, we can come a lot closer to ending it.

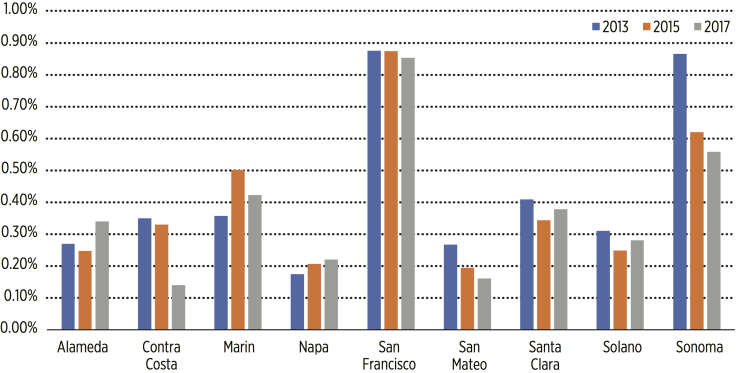

Figure 1: Homeless Population as a Percentage of Total Population

From 2013 to 2017 seven Bay Area counties saw a net decrease in their homeless populations as a percentage of their total populations, while Alameda saw the greatest increase over the past two years, at 0.09 percent.

From 2013 to 2017 seven Bay Area counties saw a net decrease in their homeless populations as a percentage of their total populations, while Alameda saw the greatest increase over the past two years, at 0.09 percent.State of the Streets

Our public spaces and city streets are not safe or appropriate places for life-sustaining activities such as sleeping or eating or going to the bathroom. Conducting these activities in public is dehumanizing for the individuals who have no other choice, and it’s difficult, even dangerous, for everyone in the city to live amid such despair.

The tent encampments that have sprung up around the region, the variety of illegal activities that occur in them, the increased public drug use and the disproportionate impacts on certain neighborhoods, raise difficult questions about how to effectively and ethically manage troubling street behavior. We believe that communities have to enforce standards of decent behavior on the streets yet not all of the troubling street behavior is attributable to the homeless population. Solving homelessness does not mean we will solve the state of our streets.

Many cities have attempted to address this problem by enacting “sit-lie” ordinances, and last year San Francisco voters passed Proposition Q to more swiftly clear tent encampments. Thus far, these measures have proven ineffective, and they come with unintended negative consequences such as reinstitutionalizing many individuals in the criminal justice system; redirecting local budgets from homeless services to the criminal justice system; and shuffling unwanted street activities from one neighborhood to another.

For as long as we have people living on the streets, we will be deeply involved in managing rather than solving the problem. We are going to have to continue to work through difficult tradeoffs and moral dilemmas as we strive to act in thoughtful, compassionate ways while maintaining the safety, cleanliness and livability of our neighborhoods.

Who Experiences Homelessness?

The people who experience homelessness are not a monolithic group. Single adults, families and unaccompanied youth may enter and exit homelessness at different points in their lives and for different reasons. For many of us who have housing, our perception of who experiences homelessness is likely to be incomplete. The people who are most visible on the street are just a fraction of those who are unhoused or underhoused, and they aren’t necessarily representative of the greater population of people who are homeless.

Government agencies and homeless service providers define homelessness in several different ways. The most widely used definition comes from the 2009 federal HEARTH (Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing) Act, which includes:

- People living in places not meant for human habitation

-

People living in emergency shelters or transitional housing facilities;

-

People at imminent risk of homelessness (of losing housing within 14 days with no other place to go and no resources or support networks to obtain housing); and

-

Families or unaccompanied youth who are living unstably.[1]

These differing experiences of homelessness can be understood more easily by looking at three classifications commonly used by government agencies and service providers to identify populations and allocate resources:

Temporal Patterns:

- Chronic: A person who is unhoused for at least 12 months consecutively or on four separate occasions over the past three years, and with a disabling condition.

- Episodic: A person who has experienced homelessness once or several times for fewer than 12 months total.

- Crisis: A person who has lost stable housing due to a crisis, such as a natural disaster.

Sheltered Status:

- Sheltered: A person who is living in a publicly or privately operated shelter.

- Unsheltered: A person who is living in a place that is not designed as a sleeping accommodation for human beings.

-

Unstably housed: A person who is at imminent risk of losing housing, temporarily living doubled up with family or friends

Demographics

- Unaccompanied youth: A person who is 12 to 25 years old and not living with parents or parental figures.

- Families

- Single adults

- Veterans

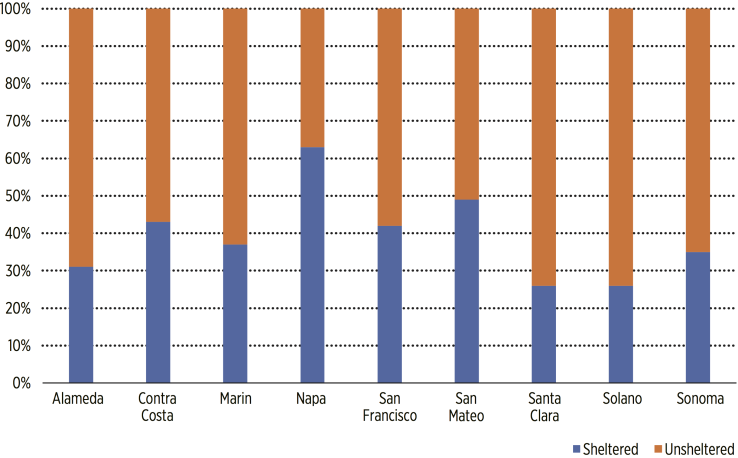

Figure 2: Sheltered vs Unsheltered Populations

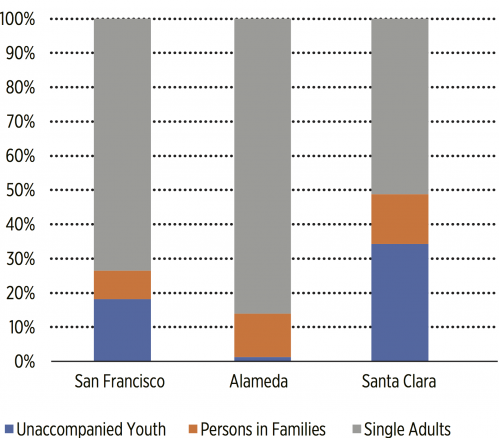

Figure 3: Subpopulations by County

What Is the State of Homelessness in the Bay Area Today?

Many Bay Area residents have noticed an increase in the prevalence of homelessness over recent years. The emergence of tent encampments, greater concentrations of people living on the street in certain neighborhoods, property crime and increased public drug use have made homelessness and activities commonly associated with it more visible and disconcerting.

Every two years, on a given night in January, local jurisdictions conduct a federally mandated point-in-time (PIT) count to estimate the number of sheltered and unsheltered people experiencing homelessness. While many believe that the PIT systematically undercounts homeless population by as much as 25 percent (due to the difficulty of identifying those who are unsheltered), these counts are our most reliable estimate of the homeless population across the country and provide useful information on trends.

According to the PIT counts from 2013 to 2017, seven Bay Area counties (Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Solano and Sonoma) have seen a net decrease in their homeless populations as a percentage of their total population. Alameda saw the greatest increase over the past two years, at 0.09 percent, with a total of 5,629 individuals counted during the one night in January.

The PIT count typically breaks the homeless population into a few subpopulations, such as single adults of 25 years or older, persons in families and unaccompanied youth. The majority of individuals experiencing homelessness in the Bay Area’s three urban counties are single adults, comprising 74 percent of the homeless population in San Francisco, 86 percent in Alameda and 51 percent in Santa Clara. In Santa Clara County, unaccompanied youth make up a particularly high percentage (34 percent) of the unhoused population.

Figure 4: Bay Area Cities Compared to Other U.S. Cities

Comparing the Bay Area to the Rest of the United States

Over the past decade, the number of Americans who have experienced homelessness has decreased slightly, from 647,258 in 2007 to 549,928 in 2016 (the last time national data was available).[2]

For the latest comparative data, we must turn to the 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress. It can be difficult to compare San Francisco to other U.S. cities, as most PIT data is collected at the county level. (San Francisco is both a city and a county, whereas the Los Angeles PIT count includes its suburban population as well.) Regardless of how the comparisons are made, San Francisco has one of the nation’s highest percentages of homelessness, alongside Washington DC, Boston and New York City.

In 2016, San Francisco had the third highest percentage of its total population experiencing homelessness, at 0.80 percent, after the District of Columbia (1.23 percent) and Boston (0.93 percent). Santa Clara County and San Francisco also had the second and third highest rates of unsheltered populations, respectively. In fact, all the western cities and counties had significantly higher rates of unsheltered than East Coast cities and counties.

For anyone who believes, based on their own eyes, that San Francisco has the worst problem with homelessness in the country, this statistic — the number of unsheltered homeless people per capita — is the “smoking gun.” East Coast cities have adopted a very different set of strategies, emphasizing shelters as a low-cost, temporary solution and in many cases forcing people to go into those shelters, as opposed to allowing them to choose to sleep in public spaces. Indeed, New York State has a “right to shelter” law that compels the city and state to provide shelter beds to all New Yorkers who are homeless by “reason of physical, mental, or social dysfunction.” While some critics decry the New York approach as “warehousing” homeless people, it’s clear that they have been vastly more successful than large California cities in getting people at least minimal shelter and in addressing the quality of life impacts on city residents. By making “real housing” with wraparound social services the only acceptable solution, without having enough money to actually scale up that solution, Bay Area cities, especially San Francisco, have created the conditions in which thousands of people are living on the streets.

The Magnet Effect

There are those that believe that factors like social services, subsidized housing or moderate climates act as a magnet to attract homeless populations. From our review of the evidence. it appears that big cities across the United States do have this effect — but mostly at a regional level. That is, people migrate from the smaller cities and suburbs to the larger central cities, but few actually migrate longer distances than that.[3]

According to the point in time count (which, because it relies on self-reporting, may not tell the full story), the majority of the individuals who are experiencing homelessness in the Bay Area are long-time Bay Area residents. In Alameda County, 82 percent of individuals became homeless in the county, and 57 percent had lived there for 10 or more years. In Santa Clara County, 83 percent of individuals became homeless in the county, and 61 percent had lived there for 10 or more years. In San Francisco, 69 percent of individuals became homeless in the county, and 55 percent had lived there for 10 or more years.

San Francisco is somewhat of an exception, as it does have a higher percentage of individuals who became homeless elsewhere: 31 percent of individuals counted during the 2017 PIT came from outside San Francisco, and many were newly homeless. Of the 3,149 individuals counted who had been homeless for less than one year, almost one-third (about 1,000) came from outside San Francisco.[4] The City helps roughly 2,000 individuals exit homelessness each year, but with an annual influx of roughly 1,000 newly homeless individuals from other cities, the cycle continues.

Why does San Francisco attract a greater portion of the homeless population? In addition to the usual attraction of central cities, another explanation may have to do with unaccompanied youth. A Larkin Street Youth Services report from 2014 found that 39 percent of youth experiencing homelessness in San Francisco came from outside California, and that of those who were California residents, 35 percent came from outside the Bay Area. One factor that may explain this high percentage of youth from other regions is that a disproportionate number of them identify as LGBTQ and end up in San Francisco when they flee from discrimination in their homes or communities.[5]

Why does this question of the magnet effect matter? On the one hand, discussing the origin of our homeless population may cause us to see people experiencing homelessness as “other” and to deem them less worthy of our compassion. On the other hand, in a region with insufficient housing and services, providers have to make difficult choices in how to allocate scarce resources. Everyone should be served, regardless of where they come from, but without funding from the federal government—which is to say, from taxpayers in other parts of the country—there is no way this small region can ever provide for everyone in need who might choose to come here. At a minimum, we need investments from the entire region to help pay for the services that the larger central cities are willing to provide.

How Did We Get Here?

Homelessness has always existed in the United States, but it has not been this prevalent since the Great Depression. In his 1944 State of the Union address, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared a “second bill of rights” that included “the right of every family to a decent home.”[6] The subsequent creation of the social safety net and strong economic growth significantly reduced the number of Americans experiencing homelessness. Poverty certainly persisted during this period, particularly for people of color and female single-headed households, but many of the poorest Americans were able to find adequate shelter — often in informal housing options such as single room occupancy hotels (SROs) or other temporary and unconventional building types that are no longer permitted today.[7]

This history provides us with reason for optimism: Homelessness has been addressed successfully in the past, and it could be again. past, and it could be again. But we should not be naïve about just how big the forces are that we are up against. It also demonstrates that homelessness is as much if not more of a structural problem (the result of poor public policy) than it is a human problem (the result of poor individual choices). A combination of several structural factors like global economic trends, federal spending, and criminal justice policy can increase the likelihood that our most vulnerable citizens will lose their housing after a personal crisis.

Several structural changes over the past few decades have led to the resurgence of homelessness today.

1. Economic Dislocation

Changes in the global economy have led to the decline of manufacturing and the growth of both knowledge and service sector jobs. Many types of occupations, including some that once paid good wages, have shrunk or disappeared. Meanwhile, for most of America, wages have stagnated since 1970 due to lower rates of unionization, the decline of antitrust regulations and other factors. The Great Recession of 2008 and its uneven recovery further exacerbated these trends. Some people were thrown out of the workforce and have not been able to reenter, while housing prices have risen ever higher. Today, households need to contribute a significantly larger portion of their shrinking total income toward housing than they did in previous decades.

2. Reduced Social Safety Nets

For the past 40 years, the federal government has made repeated decisions to stop supporting our nation’s poorest and most vulnerable citizens. In the 1970s, large numbers of individuals with mental illness were “deinstitutionalized,” or released from psychiatric institutions, without the replacement of adequate community support programs (see the sidebar “Homelessness and Mental Health”). In the 1980s, the Reagan Administration made cuts to Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), which provided financial assistance to children in families with low or no income; in the 1990s, the program was entirely eliminated in the name of “welfare reform.” At the same time, long-term assistance programs were replaced by the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families program. Throughout these decades, benefit programs for single adults like General Assistance, Supplemental Security Income and Social Security Disability Insurance all became more difficult to qualify for.[8]

3. Failed Housing Policy

Federal funding for affordable housing has been cut repeatedly, starting in the 1970s, and most notably by under the Reagan administration, which cut the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development budget by 80 percent. Today, the majority of federal funding for affordable housing comes not from the U.S. government, but from an incentive to the private sector through the Low Income Housing Tax Credit, while the biggest housing subsidies come from the mortgage interest deduction and capital gains exclusions for home sales. These federal subsidies for homeowners far exceed the federal subsidies for low-income renters. The result of these cuts has been a significant deficit of affordable housing.

But the problem is not only with the federal government. Bay Area communities have refused to build enough housing to accommodate the population, and in so doing have made this the most expensive housing market in the country. Every county in the Bay Area has failed at this fundamental task of urban governance.

4. Mass Incarceration

The rise of homelessness in the United States coincided with the rise of mass incarceration. The Nixon administration’s War on Drugs in the 1970s, mandatory minimum sentencing in the 1980s and “three strikes” laws in the 1990s all resulted in the number of incarcerated people in the United States skyrocketing from roughly 500,000 in 1980 to more than 2.2 million in 2015.[9] Individuals with involvement in the criminal justice system have greater difficulty finding employment and qualifying for subsidized housing, and therefore a greater risk of experiencing homelessness.[10]

5. Family Instability

Several of the previously cited structural causes, such as income inequality and reduction in social safety nets, have led to instability that puts entire families and youth at greater risk of homelessness. Across the country, families comprise about one-third of the total homeless population. They are usually headed by a single woman, who is on average in her late 20s, with approximately two young children. The high cost of childcare, lack of flexible employment opportunities, lack of parental leave and domestic violence all increase a family’s risk of homelessness.[11] Youth who grow up in unstable or unsafe homes are at greater risk of experiencing homelessness, particularly those who identify as LGBTQ and come out to significant negative reactions from their families. (San Francisco’s 2017 point-in-time count found that 49 percent of youth experiencing homelessness identified as LGBTQ.) Additionally, involvement with child welfare services has a high correlation with homelessness. When aging out of the foster care system, youth often lack the financial resources and social networks to support themselves.

6. Structural Racism

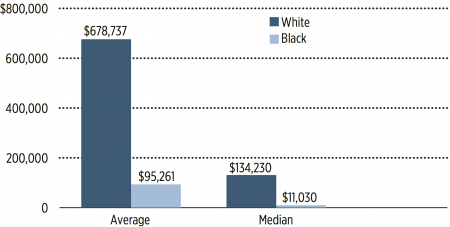

Across the country, people of color are dramatically overrepresented in homeless populations. In 2015, African Americans represented 40 percent of the U.S. homeless population, despite represent-ing only 13.3 percent of the general population.[12] This disparity is a result of structural racism in the United States, particularly in housing. Until the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, it was legal for landlords, sellers and developers to refuse to rent or sell housing to African Americans and other minorities. Meanwhile, from the 1940s to the 1960s, many predominantly African American urbanneighborhoods were bulldozed in the name of “urban renewal.” Because of our national emphasis on home ownership, housing equity makes up about two-thirds of all wealth for the typical household in the United States. Yet decades of racism in the housing market have resulted in an enormous racial wealth gap, with white households having seven times more wealth than African American households. More than one in four African American households have zero or negative net worth.[13] Without the financial assets to serve as a buffer in times of personal hardship, and with greater sensitivities to other structural changes mentioned above, African Americans are three to four times more likely to experience homelessness than other Americans.[14]

Figure 5: Media and Average Wealth, by Race

7. Individual Causes

Homelessness can happen to anyone. While one distinct crisis — such as a job loss or a medical crisis — is often cited as the primary cause of homelessness, more often homelessness is a result of multiple and compounding causes. Those that are most cited by individuals in the point-in-time count are:

- Economic instability — The loss of a job, an unexpected expense or eviction (which is both a cause and consequence of economic instability).

- Trauma, loss of family safety nets — A divorce or the death of a family member results in the loss of the family home.

- Institutional exits — Institutions such as the armed forces, foster care, prison system or hospitals exit individuals onto the street.

- Mental illness (including substance abuse) — A mental health condition makes it particularly difficult to find or hold a job or housing.

- Disability — A disability makes it particularly difficult to find or hold a job or housing.

Across the Bay Area’s three urban counties, economic instability is the most common cause of homelessness, cited by 30 percent of individuals in San Francisco, 50 percent in Alameda and 35 percent in Santa Clara. Indeed, homelessness is primarily a symptom of poverty.

When most people experience one of the crises listed above, they don’t end up losing their homes. But for those who are at the lowest end of the income spectrum, have historically faced discrimination or have no safety net to fall back on, homelessness is a much greater likelihood.

It may be impossible to reverse the impacts of decades of federal policy decisions or do anything about the global changes in the economy. But in the Bay Area we can focus our efforts on policy solutions that impact what we do have control over at the local level. The following article will look at how we might begin to shape some policy solutions that can work.

Figure 6: Individual Causes of Homelessness

The most common cause of homelessness in the Bay Area’s three urban counties is economic instability. (Note: Each county reports slightly different categories of causes.)

The most common cause of homelessness in the Bay Area’s three urban counties is economic instability. (Note: Each county reports slightly different categories of causes.)What Does “Solving” Homelessness Look Like?

We may never be able to end homelessness. Vulnerable populations will always be susceptible to crises that can lead to the loss of housing. However, we can prevent it whenever possible and, when it does occur, we can make it rare, brief and nonrecurring.[15]

Different populations require different interventions, but there is a common core to homeless solutions everywhere:

1. Deploy deep interventions for the chronically homeless and disabled.

People who experience chronic homelessness or have severe disabilities have complex service needs that can be very costly to provide, making it difficult to get rehoused. The research is overwhelmingly clear: Permanent supportive housing using a “housing first” approach (offering housing without any preconditions like addressing substance abuse or unemployment) produces the best outcomes and may offset some costs of public services such as emergency shelters, hospital emergency room and inpatient care, sobering centers and jails.[16,17] The housing first approach is based on overwhelming evidence that stable permanent housing is a necessary foundation before anyone can resolve health issues, pursue personal goals or improve their quality of life. Permanent supportive housing is highly effective at targeting the most vulnerable population. It also provides housing with no time limit and wraparound supportive services that promote residents’ recovery and maximize their independence.

The dilemma for public policy is that this best solution is too expensive to scale to be the only solution. We will probably never have enough permanent supportive housing with wraparound services to provide it for everyone. Major effort needs to go into strategies for driving down the cost of housing construction, more efficiently providing services and increasing the likelihood of people exiting from supportive housing into less expensive residences. We will have to be realistic about using other, second-best solutions for the people who are not able to get supportive housing.

2. When homelessness occurs, respond rapidly to make it short-term.

Preventing people from escalating from episodic homelessness into chronic homelessness would have a huge positive multiplier effect across the system. Several interventions can shorten the experience of homelessness and rapidly respond to help the most vulnerable get or return to housing.

In many communities, accessing homeless housing or services requires interfacing with multiple organizations, each with its own intake processes and long wait times. Some cities are trying new coordinated entry systems, which help people receive resources that meet their specific needs more quickly by condensing all provider intake processes into one.

Emergency shelters provide an essential short-term respite for people who are experiencing a housing crisis or fleeing an unsafe situation. Shelters with low barriers to entry (for example, no sobriety or income requirements) allow more individuals and families to access them.

A successful crisis response system not only ameliorates the immediate crisis of homelessness, it also helps create longer-term stability by connecting people with permanent housing opportunities. Rapid rehousing provides short-term rental assistance and services that help people obtain housing quickly without any preconditions. The Family Options Study commissioned by HUD from 2010–2012 found that while rapid rehousing was the most effective crisis intervention, long-term housing subsidies such as Section 8 vouchers were most effective for ending family homelessness.[18] Increasing the availability and portability of those vouchers, as well as working with more landlords to accept them, could increase the efficacy of these interventions.[19]

3. Prevent homelessness before it starts.

Even if a community is able to house all of its residents, the problem will persist if new entries into homelessness are not prevented. The leading preconditions for homelessness are well known, and interventions can be targeted accordingly.

Exits from criminal justice, health care, child welfare system and military institutions can be better managed so individuals are discharged into stable housing, rather than onto the street. Those individuals should also be connected with mental health services, substance abuse counseling, education and employment assistance.

Low cost interventions can help keep people from losing their housing as a result of a nonrecurring crisis, such as an eviction, mortgage foreclosure, child custody or support disputes, or debt collection. A one-time cash infusion of as little as $1,000 to cover anything from rent to car payments has proven to prevent homelessness for up to two years.[20] Legal aid can also help prevent nonrecurring crises from resulting in loss of housing.

Many people at risk of homelessness move in temporarily with other family members, commonly called “doubling up,” which is one of the most promising and least costly interventions for certain populations. However, lease restrictions, benefit eligibility and interpersonal strain can all prevent this from being a viable solution for longer periods of time. Legal aid or counseling can help reduce some of these barriers for friends and families.

But we cannot prevent homelessness without providing sufficient housing. Even with healthcare, counseling, legal aid and rental assistance, our most vulnerable will end up on the street if we don’t have enough affordable housing for everyone who needs it. More housing is needed at all income levels, particularly housing that is affordable for the lowest income residents (those earning 0 to 30 percent of area median income), and more housing subsidies are needed to help those low-income residents access the housing we currently have.

If we know how to address homelessness, why haven’t we made significant progress? We need to acknowledge that this is an extremely complex and challenging problem, with deep structural causes that are national in scope, and that housing solutions are particularly difficult in the most expensive region in the country. But while we may not be able to end homelessness completely, we can do a better job at deploying solutions for the most vulnerable, responding rapidly when homelessness occurs and preventing it before it starts. This requires us to be honest about what’s working and what’s not, and to make some politically difficult changes.

Homelessness and Mental Health

The deinstitutionalization of individuals from state mental health systems from the 1960s through the 1980s is often credited with the rise of homelessness across the United States. Due to inadequate investments in community-based support immediately after deinstitutionalization, individuals with mental health disorders and substance abuse issue were more likely to become homeless. However, by the mid-1990s, the Bay Area had built an Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) program to provide health care, housing, vocational training and 24/7 support for those with severe mental illnesses. Today, many individuals with the most severe mental health issues in the Bay Area are eligible for and receive good care.In addition, permanent supportive housing was modeled after ACT programs to fill gaps for those with less severe mental health issues though we don’t have an adequate amount to house them all.

While it is true that many people who have mental health conditions experience homelessness, the inverse is also true: becoming housed improves mental and overall health. Research by Dr. Margot Kushel at the University of California, San Francisco has found that homelessness has devastating consequences to health. Individuals experiencing homelessness have poor access to medical care, which leads to underdiagnosis and greater difficulty managing chronic health problems like arthritis or diabetes. That can trigger underlying mental health issues, which can then lead to substance abuse. Yet when individuals are rehoused, their overall health improves greatly. This research provides further support that providing housing without preconditions, an approach known as “housing first,” works when we can come up with the money to provide it to people.

Promising Progress: Santa Clara County’s Destination: Home

One Bay Area county has recently taken a good look at their approach to the issue and made some bold moves: Santa Clara.

For years, the county’s safety net agencies, health care providers, homeless services providers and affordable housing providers conducted their well-meaning work alongside one another but not in partnership. The homeless crisis, and frustration with it, continued to mount until a few bold city leaders decided they could do better. In 2007, then Santa Clara County Supervisor Don Gage and then San Jose Mayor Chuck Reed convened a Blue Ribbon Commission on Homelessness and Affordable Housing to better examine the problem and implement effective countywide responses to it. The outcome was the creation of a new public-private partnership organization called Destination:Home, which would serve as the backbone organization for collective impact strategies across the county.

Under the leadership of its executive director, Jennifer Loving, Destination:Home has transformed the way Santa Clara County tackles homelessness in a few significant ways:

1. Cross-sector collaboration

As the central organizing entity for community wide entities to end homelessness, Destination:Home brought together leaders from the private and public sectors throughout the county, including government officials and local housing authorities.

2. Sustained, comprehensive strategy

In 2014 Destination:Home led the creation of a community-wide road map to end homelessness. The plan provides a collective impact model that guides governmental actors, nonprofits and other community members as they make decisions about funding, programs, priorities and needs. Destination:Home ensures that all stakeholders maintain their commitment to the plan by demonstrating successful strategies, data and outcomes on behalf of the consortium of agencies who are ending homelessness together.

3. Better data and tracking

Santa Clara County was the first Bay Area county to build a coordinated entry system, which requires all homeless service providers to share a single database in order to measure the same things and ensure the most cost-effective interventions. In 2015 the County of Santa Clara and Destination:Home also conducted the most comprehensive cost assessment of homelessness in the country, which was no small feat as it required diverse government agencies, nonprofits and private institutions to share sensitive, and often HIPAA protected data.

4. More efficient spending

Destination: Home Not Found cost study served as the foundation for the County of Santa Clara’s Welcome Home project, one of the country’s first pay-for-success models, which focuses on an integrated data system serving the most vulnerable chronically homeless individuals in partnership with Abode Services.

Santa Clara County is starting to see the results of these changes. Over the last two years, the Santa Clara County community has permanently housed approximately 3,000 households, including 700 veterans, with a retention rate of over 85%. In 2016 the County of Santa Clara placed a $950 million housing bond on the ballot successfully, with the goal of creating more than 4,500 units of supportive and extremely low income housing, and in 2017 Destination:home and their partners came together to launch a new $3.5 million homeless prevention system focusing on families at risk of homelessness.

While the progress is promising, Santa Clara County faces the same challenge that the rest of the region faces. While local residents have voted for new funding for ELI and supportive homeless housing, they have regularly opposed the siting of it in their neighborhoods. In early October, just as this article was going to print, San Francisco’s Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing released a new strategic framework for addressing homelessness that aims to tackle many of the same systemic problems Santa Clara has in recent years, with many of the same solutions.[21]

Where Do We Go From Here?

While the challenges are great, the Bay Area has the ingenuity and resources to address them. We need to stop what’s not working, expand what is working, create more comprehensive strategies and stick with them over the long-term. It has taken us many decades to create this problem, and it may take many years to solve it. Any solution will require patience.

While SPUR helps policy-makers and service providers grapple with the difficult questions that lie ahead – such as, how do we manage tent encampments, how many more shelter beds do we need, how much should we be spending on different populations, and what might regional collaboration look like — individual residents of the Bay Area can contribute to solutions today.

Here are some steps we all can take:

- Educate others and dispel myths about the causes of and solutions to homelessness.

- Advocate for policy solutions in at the city, county and state level.

- Show our support for more housing development in our neighborhoods by writing our elected officials, showing up at hearings and voting.

- Those who are landlords or who have extra space on their property can make spare units available to formerly homeless individuals and families.

- Support our local homeless service providers by volunteering or donating.

- Engage with individuals who are experiencing homelessness in our neighborhoods by asking how we can support them, calling for medical assistance if they’re in need or offering a sandwich or pair of new socks.

Addressing homelessness will require the entire Bay Area community’s support.

- The National Alliance to End Homelessness. “Summary of the HEARTH Act.”

-

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Community Planning and Development. “The 2016 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress.” November 2016.

-

Interview with Igor Popov, July 21, 2017.

-

San Francisco Department of Housing and Homeless Services.

-

Larkin Street Youth Services. “Youth Homelessness in San Francisco: 2014 Report on Incidence and Needs.”

-

FDR Presidential Library & Museum. “75th Anniversary of the Wagner-Steagall Housing Actmof 1937.”

-

Jessica Nicholas. “Homelessness in the United States and San Francisco.” Prepared for Tipping Point Community. September 2016.

-

ibid.

-

NAACP. “Criminal Justice Fact Sheet.” http://www.naacp.org/criminal-justice-fact-sheet/. Accessed August 27, 2017.

-

Jessica Nicholas. “Homelessness in the United States and San Francisco.” Prepared for Tipping Point Community. September 2016.

-

United States Interagency Council on Homeless-ness. “Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness.” June 2015.

-

Nicholas, “Homelessness in the United States and San Francisco.”

-

Janelle Jones. “The racial wealth gap: How African-Americans have been shortchanged out of the materials to build wealth.” Economic Policy Institute. February 13, 2017.

-

Interview with Dr. Margot Kushel, UCSF August 2017.

-

United States Interagency Council on Homeless-ness. “Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness.” June 2015.

-

ibid.

-

Stefan G. Kertesz, Travis P. Bagget, James J. O’Connell, David S. Buck and Margot B. Kushel. “Per-manent Supportive Housing for Homeless People – Reframing the Debate.” New England Journal of Medicine. December 1, 2016.

-

National Alliance to End Homelessness. “Findings and Implications of the Family Options Study.” July 7, 2017.

-

Interview with Margot Kushel, August 7, 2017.

-

David Shultz. “A bit of cash can keep someone off the streets for 2 years or more.” Science Magazine. August 11, 2016.

-

“SF’s ambitious homeless strategy seeks sharp cuts, coordinated outreach,” by Kevin Fagan, San Francisco Chronicle, October 2, 2017