Amy Liu is vice president and director of the Metropolitan Policy Program at the Brookings Institution. This essay was adapted from a keynote address she delivered at the annual SPUR Board of Directors retreat in March 2018.

Whether Bay Area residents like it or not, city leaders across the country are watching how this high-tech region grapples with the consequences of dizzying economic growth — expensive housing, stark inequalities and congestion, to name a few. While the most obvious policy failures may lie with transportation and housing, focusing on the built environment alone is insufficient. The economy matters too. Increasing the availability of good-paying jobs and training more local workers for stable careers can help residents earn enough to keep pace with the region’s rising cost of living. This region is adept at attracting talented workers from across the world to take lucrative positions in fast-growing tech-savvy companies. Yet more must be done to help existing residents access quality jobs in the innovation economy and in the industries that support it.

The Bay Area confronts two futures: one in which innovation and economic growth continue to drive social upheaval and inequities; and another in which leaders in business, government and the civic sector work together to help everyone in the region to participate in — and contribute to — economic growth. As America’s undisputed capital of the innovation economy, though, the Bay Area stands apart. Its path in the years ahead could serve as an exemplar to other regions for how to navigate economic inclusion in the 21st century — or as a cautionary tale.

In pursuing the second future, leaders across the region would do well to understand the economic challenges we face, and to consider a wider set of strategies that can make the Bay Area a center of innovation and inclusion.

Why growing an inclusive economy is so important

Every year, the Brookings Institution publishes a report called the Metro Monitor, that tracks the economic performance of the 100 largest metro areas in creating economic growth, prosperity and inclusion. The Metro Monitor helps us answer a few questions: it tells us if a metro area’s economic pie is expanding; if this growth has boosted productivity and living standards; and whether the metro area’s population is better off along measures of inclusion, including by race and educational attainment.

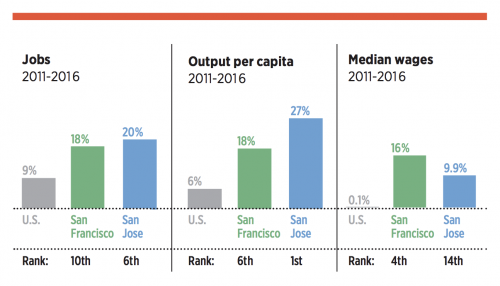

The Bay Area has experienced remarkable economic growth in recent years. As most residents know, the San Jose and San Francisco metro areas have outperformed the national averages and nearly all other metro areas on job creation, productivity and median wage growth over the past five years. Moreover, while employment rates for whites have stayed about the same since the 2008 recession, employment rates for workers of color have improved — from 60 to 68 percent — closing the gap with white workers.

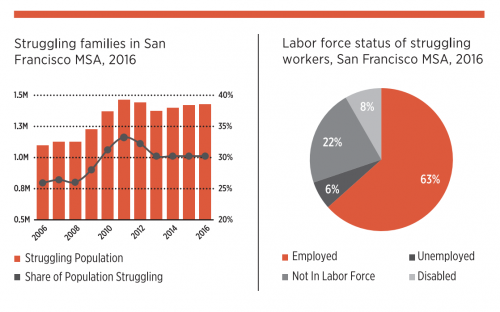

At the same time, one-third of Bay Area residents — nearly 2 million people — struggle to make ends meet. As local political debates suggest, many residents struggle to afford the costs of housing, transportation, childcare, food and healthcare in this strong economy, and that number has risen dramatically in the past 10 years. Two-thirds of these struggling families have at least one adult with a job. This suggests a need for more reasonable living expenses, more jobs that pay a living wage, and more education, training or supports for workers so that adults can access better jobs.

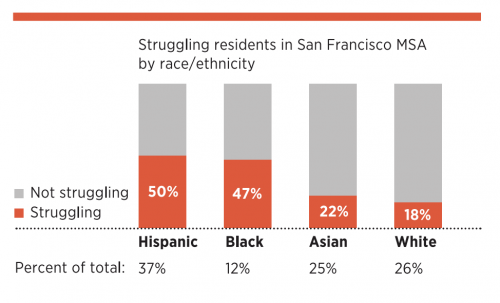

Furthermore, the Bay Area faces stark racial disparities. Nearly half of all black and Hispanic residents in the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas do not earn enough to meet daily living expenses. Yet no group is immune to the challenges of making ends meet in this region: Nearly one in four white and Asian residents do not earn enough to achieve self-sufficiency, representing half of the total struggling population.

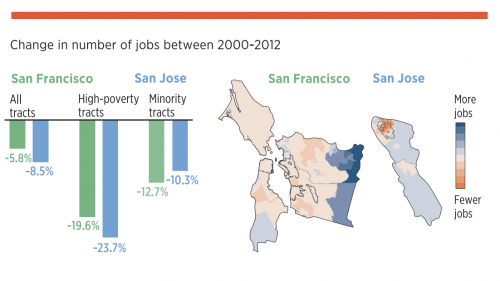

Within the Bay Area, proximity to jobs is declining. According to Brookings analysis, jobs grew fastest on the outskirts of the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas between 2000 and 2012, and declined slightly in the most urbanized areas. The result is that residents across all neighborhoods in the Bay Area live near fewer jobs than they did at the turn of the century. Moreover, in both the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas, the decline in the number of nearby jobs has been much worse for high-poverty and majority-minority neighborhoods. While job growth in recent years could be easing or exacerbating these trends, there is no mistaking the need for a better balance of jobs, housing and transportation throughout the Bay Area.

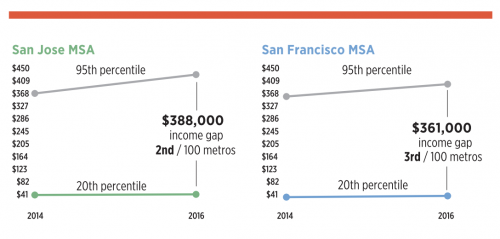

All this inequality — by race, income, and geography — imposes costs, including on the region’s capacity to innovate. As the following two graphics show, the San Francisco and San Jose metro areas have the second and third widest income gaps between high earners and low earners across the country’s largest metro areas. A family at the 95th percentile of income earners in San Jose makes $429,000 annually, while a family at the 20th percentile makes just $41,000. Incomes at both levels grew between 2014 and 2016, but the overall gap widened.

Stanford researcher Raj Chetty and his team examined the impact of wage inequality on entrepreneurship. They found that children who were born into wealthier households were much more likely to become an inventor and produce a patent than those from poorer households. In other words, kids born to poorer families did not have the education and tools needed to later develop the kind of technologies and innovations that power our economy.

The consequences of this for the Bay Area are dramatic: an estimated 51 percent of all inventors born between 1980 and 1984 came from families in the top 20 percent of income earners, while just 7 percent came from families in the poorest 20 percent. Chetty and his team estimate that if all people across race, gender and socioeconomic status were given equal opportunity to succeed, the country as a whole would have four times as many inventors as it does today – which translates to 3,800 more inventors born in the Bay Area during just a five-year window. These are who Chetty calls the “Lost Einsteins.”

In short, this research affirms that economic exclusion hampers both growth and opportunity.

How demographic change and digitalization can widen existing disparities

As leaders in the Bay Area consider the paths toward an inclusive economy, they must confront two structural forces that define the modern era: our nation’s ongoing demographic transformation into a more racially diverse and multiethnic population, and the rapid digitalization of our economy, which is transforming the nature of work and the built environment. These two forces are assets in a global economy that prizes diversity and cultural awareness in the modern workplace. Yet if leaders fail to recognize and respond to the interconnections between these two forces, they risk stalling growth and widening the disparities that exist within our society.

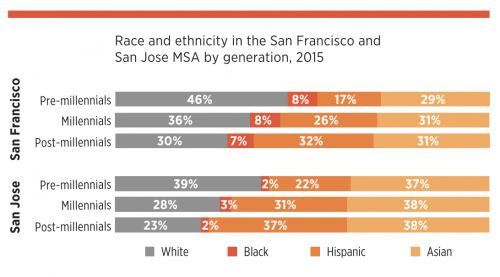

The people who are entering the labor force are more diverse than ever. The chart above shows the demographic shift underway between millennials — defined as those aged 18 to 34 in 2015 — and the generations that preceded and will follow them. In the San Francisco metro area, the older generations are approximately half white, while millennials are more than two-thirds young adults of color. The next generation will be even more diverse. In the San Jose metro area, millennials are more likely to be Asian and Hispanic than white, and that trend will continue, with the share of Hispanic residents expanding the most.

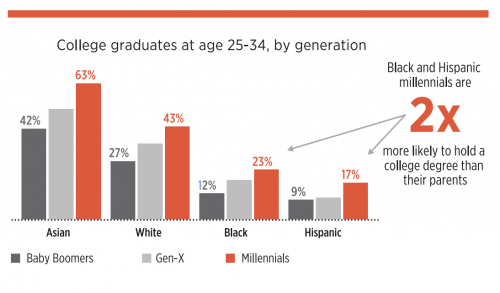

Black and Hispanic millennials are more educated than their baby boomer parents, as can be seen in the chart below. Yet the gap in educational achievement between black and Hispanic young adults compared with whites and Asians remains dramatic. Twenty-three percent of black and 17 percent of Hispanic young adults have college degrees, compared with 43 and 63 percent of whites and Asians, respectively. Despite the positive presence of many distinguished institutions of higher education in the Bay Area, the region’s educational attainment numbers mirror these national statistics. Leaders must accelerate efforts to equip black and Hispanic residents with the skills and networks they need to succeed in the modern economy.

The modern economy is being transformed by the rapid diffusion of digital technologies. Whether it’s robotics, cloud computing, mobility tech, big data or artificial intelligence, technological innovation is redefining which jobs are created, what skills are needed and what kind of urban world emerges. Thanks to these new capabilities, industries are more productive, businesses can reach more customers, and people have more choices for shopping, travel and entertainment. At the same time, digital innovation is rapidly destroying jobs, making certain skills obsolete, and leaving some workers and communities farther behind.

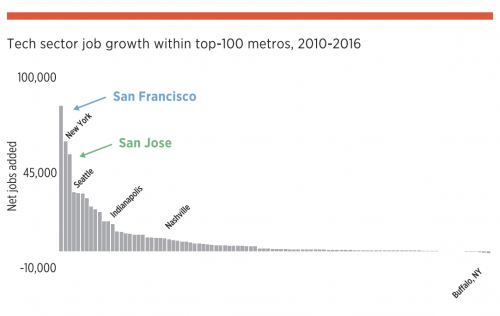

The Bay Area is the epicenter of the nation’s tech growth and disruption. Sixty percent of all new digital jobs in the United States since 2010 were created in just 10 metro areas. The San Francisco and San Jose metro areas added a net 140,000 tech jobs during that timeframe, leading all U.S. regions and increasing their concentration of American tech jobs. That dominance is not only transforming the Bay Area economy, it is also facilitating disruption nationally and globally in ways that are shaping the quality and distribution of opportunity across communities.

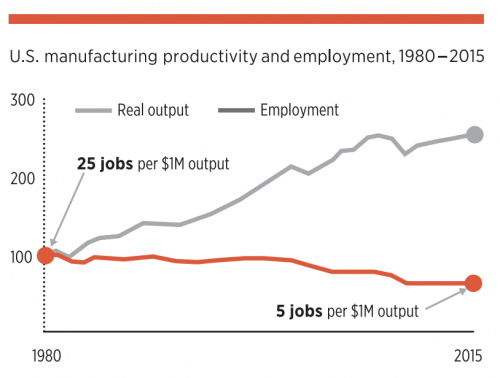

For instance, the adoption of new technologies is making manufacturing more productive and less job-intensive. Thanks to robotics and other new technologies, manufacturing is the most productive it has been in decades, generating far more with far fewer people. In 1980, it took 25 jobs to produce $1 million of output. Today, it takes only five jobs. The implications of this are clear: Though manufacturing remains a critical sector, it cannot be a primary source of good jobs for workers and communities in the years ahead.

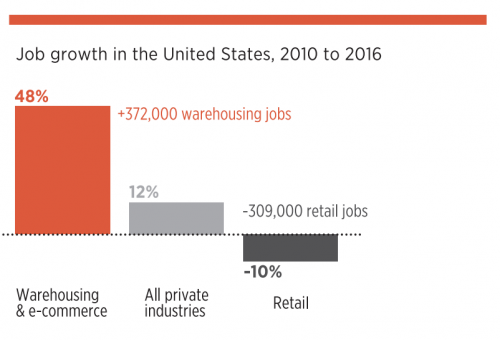

The services sector, including retail, is undergoing its own digital transformation. One example is the impact of e-commerce on the retail landscape. Approximately 6,400 retail stores closed in 2017 alone.

As shown in the graphic above, since 2010, the retail sector has shed approximately 300,000 traditional sales jobs, while jobs in warehousing, customer service and supply chain management have emerged in their place. These shifts affect cities and suburbs that depend on sales tax revenue, create uncertainty for main streets and neighborhood commercial corridors, and shift certain jobs to less accessible locations for low-skilled workers.

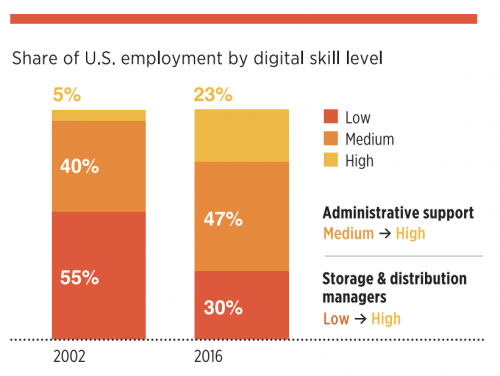

As companies and industries rapidly digitalize, so do the skills requirements for workers at all pay grades. A recent Brookings report examined the digital skills requirement of over 500 different occupations (representing 91 percent of the labor market), giving a digital skills score to every occupation based on two criteria: (1) how much specific knowledge of computers and electronics workers need to do their jobs, and (2) how frequently workers use computers and electronics in their daily tasks. What they found is that in 2002 —before Facebook, Twitter and the iPhone — 55 percent of all U.S. jobs required minimal computer skills and just 5 percent required high levels of computer literacy.

By 2016, skills requirements dramatically shifted. Jobs with low digital skills have shrunk to just 30 percent of all jobs, while 70 percent of jobs today require workers to have moderate to high digital competency. This digital skills revolution is ubiquitous, increasing the demand for software engineers while upgrading the tasks of critical pathway jobs to the middle class, such as administrative assistants, tool and die makers, police officers and distribution managers.

For workers, it pays to be digitally savvy.

Our research shows that mid-tech and high-tech jobs pay more, creating opportunities for workers able to reach those jobs. U.S. workers whose jobs require low levels of digital skill, including construction workers and cooks, earn a median income of $30,000. Workers using moderate levels of digital skills, including service mechanics and registered nurses, typically earn $48,000 each year. Meanwhile, the median wage of jobs that require high levels of digital skill, including financial managers and software developers, is $73,000.

The opportunities extend beyond coding: Workers who use Salesforce, Adobe Photoshop or Microsoft packages like Excel and PowerPoint on a daily basis could be more likely to earn higher wages in today’s economy.

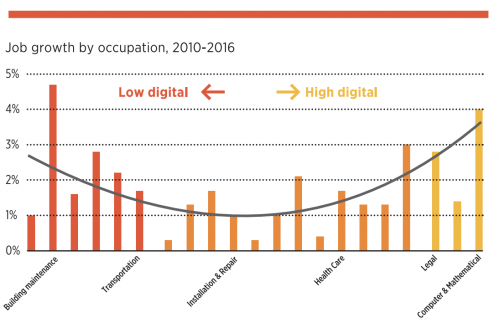

Unfortunately, the rise of digitalization is bifurcating opportunities by income and race. The digital economy appears to be growing faster in high-tech, high-wage and low-tech, low-wage jobs than mid-tech ones, limiting opportunities for workers to move up and earn middle-class pay.

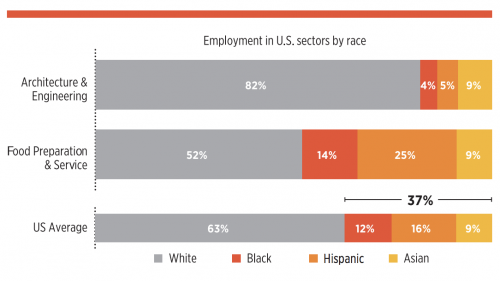

Furthermore, white workers are much more likely to access well-paying tech jobs, while workers of color are underrepresented in higher paying, highly digital occupations such as computer programming, architecture and engineering. Even though people of color represent 37 percent of all workers today, black and Hispanic Americans are disproportionately likely to hold low-tech, lower-paying jobs like home health aides and food and hospitality workers.

In sum, the task of building a digital economy that generates broad-based opportunity is a fundamental challenge facing every city and metro area. It is particularly acute for the Bay Area, where the origin and consequence of technology disruption, coupled with an already majority-minority workforce, is coming to a head. The region’s wide income and racial disparities are testing the area’s social and political cohesion, and sense of community and quality of life.

What Bay Area leaders can do, together, to advance inclusive growth in this digital age

SPUR and its many partners are launching an unprecedented regionwide collaboration1 involving the whole civic community — government, businesses, higher education, community nonprofits and philanthropic organizations. Yet businesses, employers and the economic development community have an additional responsibility to make an inclusive economy possible. They are the job creators, the hirers and the investors in the economy. The private sector often sets and influences the economic agenda and raises funds for catalytic initiatives.

So how can leaders in the Bay Area create a truly inclusive economy?

Fundamentally, economic inclusion is not a single program but a value that should permeate across mind-sets, organizations, collaborations and strategies. What is needed in communities is a massive culture shift.

Change starts with individuals, especially at the top. The Bay Area needs more CEOs, mid-level managers and everyday workers to articulate the importance of diversity and inclusion and why expanding opportunities for more people is good for their organizations and the community. For instance, CEOs who chair the top economic development group in greater San Diego are advancing a more honest narrative about the region’s prospects: that San Diego’s innovation future hinges on the region’s capacity to improve the educational achievement of Hispanics, the fastest-growing segment of the local labor force; support women and minority entrepreneurs; and expand affordable housing. In short, economic inclusion is increasingly seen as critical to San Diego’s global competitiveness.

Individuals must then lead by example by driving the value of economic inclusion into organizational missions. An increasing number of economic development entities, other business groups and local governments are making tangible changes ranging from hiring new staff to carry out economic inclusion commitments to reexamining how existing organizational programs, like economic development subsidies, can be less exclusionary. Executives could also revise recruitment policies that open doors for job applicants who have historically been excluded and achieve greater diversity among senior staff, which research has shown to be a predictor of company success.

With organizations more authentically committed, they can then be better contributors to regional collaborations that include a diversity of voices and advance regional priorities that help people, firms and communities adapt to the rigors of the modern economy. This includes helping people with diverse backgrounds gain relevant skills, start and grow new businesses, and afford homes in neighborhoods with good jobs and schools. In greater Seattle, the Road Map Project aligns the work of hundreds of community leaders and businesses to help local students, particularly students of color, reach college and pursue good careers. In Atlanta, TechSquare Labs seeks out aspiring entrepreneurs of color, providing them with the networks, mentorship and funding they need to launch new businesses. Meanwhile, leaders of housing authorities in greater Chicago, Baltimore and other cities are working to pool public housing funds, facilitating the construction of affordable homes in opportunity-rich neighborhoods and helping families move to neighborhoods across the region.

The Bay Area is a place with unique levels of innovation and an unparalleled ability to retain first-class talent. There’s no doubt this has helped the region grow its economy. And yet, as technological and demographic forces radically change industries, it is of vital importance that leaders work to ensure this economic growth is created by and for all workers and families, regardless of which neighborhood they live in. By working to remove the formal and informal barriers to entry that too often separate some communities from the centers of power and growth, local leaders will not only be making their region’s economy fairer. They will ultimately be making it stronger.

1 “The Bay Area in Crisis: A Call to Action,” by Benjamin Grant, The Urbanist, Issue 563, March 2018